There is a surprising amount of argument about the origins of the many film sizes that have been produced since the late 1800’s. During the glory years of film photography, new film stocks and sizes were produced at an incredible rate and often just to accommodate a certain design feature or physical size of a camera model.

In a sweeping generalisation, we can summarise that amongst the dozens of film standards that have been released, really only two have stood the test of time and those are 120 or medium format and 35mm. As with everything in life, it isn’t that simple, because the size of the film used is only the beginning of how an image will actually be created on it. Take 120 film – you can shoot 9cm x 6cm, 6 x 6, 6 x 7 or 6 x 4.5 sized frames on a roll. In fact you are not limited to those frame sizes, it is up to you how you project light onto the emulsion and the very first Kodak cameras actually created fully circular images.

What on earth has this got to do with the Canon Demi? More than you’d think!

In this post:

- The Need for Half Frame

- Buying Within Reason

- Features

- Ergonomics and Handling

- Lens and Image Quality

- Conclusions and Learning

The Need for Half Frame

Believe it or not, film used to be really quite flammable. Nitrocellulose was initially used as the base for film stocks. The only issue with this is that nitrocellulose is also the base for gun powder, so you can see where this is going. Over time these stocks degrade, emit a nasty brown goo before eventually turning to dust, but only if they haven’t spontaneously caught fire in the meantime. Many cinema fires were caused by the film simply burning during use.

By the mid 1950’s, most manufacturers had switched to “Safety Film” which was a quaint way of saying “won’t burn your house down.” One of the first manufacturers of safety film was Eastman Kodak who, as nearly everyone knows, were at the forefront of photographic product innovation since pretty much the beginning. It was Kodak who inadvertently began the 35mm standard for still photography.

Kodak were producing films of 70mm width for their box cameras in the late 1800’s at the same time that Thomas Edison (genius inventor for those who don’t know) and his assistant William Laurie Kennedy Dickson had been developing a Kinetoscope. Kinetoscopes were seen by Edison as a toy, they had a small reel of film and a light inside and by spinning the frames past the light at 46fps it created lifelike moving images for the viewer. Kennedy, perhaps, had more of a hand in the design than he is historically credited for and it is argued that he, not Edison, settled on the 35mm film format they were about to invent.

There are conflicting and differing accounts about how Edison and Dickson decided on their film format for the Kinetoscope, but it is likely that they arrived at 35mm entirely by accident, or in pursuit of economy. Cutting Kodak film stock in half (70/2 = 35) to save costs made sense, rather than pursuing the manufacture of a custom size stock. Either way, in 1891, the standard of a 35mm width, with 4 perforations or “sprocket holes” per frame had been born and neither inventor saw fit to document why they had created the 35mm film size.

Many of these early innovations such as different film sizes, number of perforations and so forth were done to improve cinematic experiences. Due to the sheer amount of film required to create motion pictures, film studios, photographers and manufacturers were all looking to create or use the most economical format with the best possible results. This also led to developments in the thickness of the film, but one thing seemed to always gain traction regardless of other fads, and that was the 35mm width.

Almost all technology follows the same pattern. When newly released, things are usually large, expensive and probably unreliable. Over time, manufacturing improves, costs get cheaper, components are designed to be slimmer, more efficient and more reliable. Consequently, devices get smaller, cheaper and more powerful. This can be seen in anything from a TV, computers or even vehicles where innovations have led to ever more competent yet cheap products.

The same is true in the world of light capture. Whether for motion pictures or still photography, from 1900 onward there was always a desire to create ever smaller cameras that were more economical to run, whilst being reliable. Cinema experimented with multiple frames per 35mm film strip and for some time Pathe preferred 3 x 9.5mm frames in strips on their usual 35mm stock.

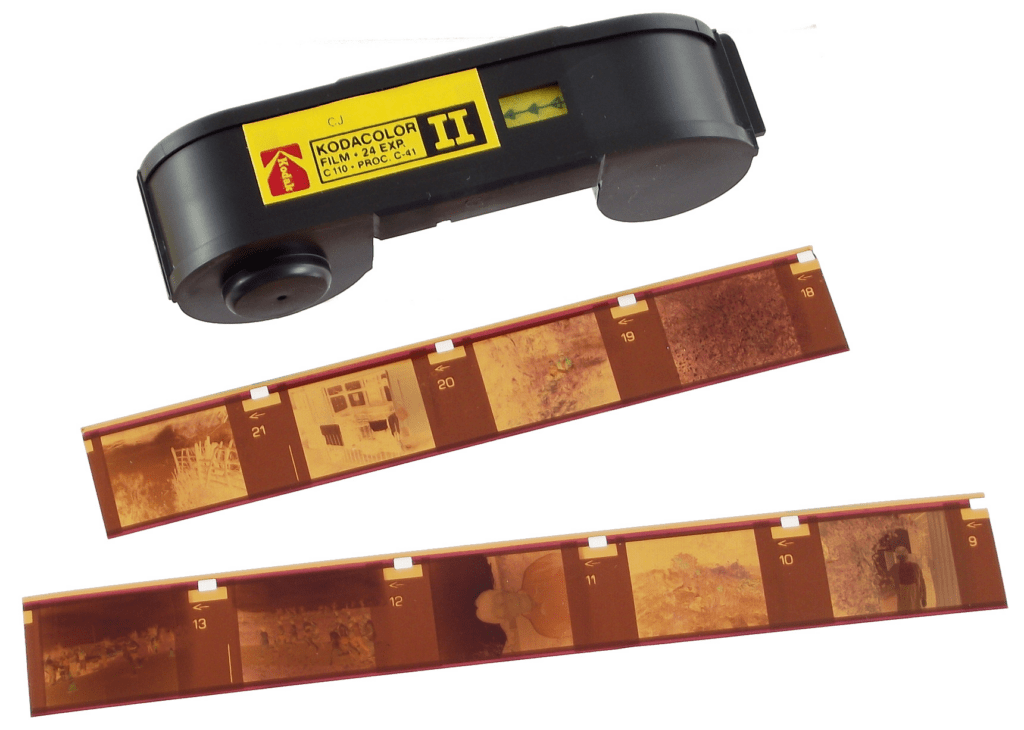

9mm was agreed to be the smallest possible frame size before there was obvious degradation in image quality and time proved this to be correct with a number of smaller film standards such as disc or 110 cartridge film falling by the wayside as their approximately 9mm x 11mm frame sizes proved to be poor even by the standards of the day and enlargements were almost impossible.

In 1960, black and white film was reasonably cheap, but colour was the next big thing. Now that films were no longer setting on fire or degrading into explosive dust, the next push was the conversion from black and white to colour photography. Methods of capturing colour images had existed since 1900, but it wouldn’t be until 1956 and C-22 processing that colour began to make it into the mainstream and 1971 and C-41 before the average photographer could afford to enter the luxury world of colour.

During this period manufacturers were pushing for miniaturisation of cameras, an inevitable goal of the technology of image capture as touched on earlier. In order to miniaturise, you need to concentrate on the largest components first, and by far the biggest part of most cameras of the time was a roll of 120 film. It had to go.

120 film, whilst capable of producing beautiful, sharp and extremely detailed negatives, was overkill for most amateurs and not exactly economical. At best, a roll of 120 will give 12 images at 6cm x 6cm or 8 images per roll if you go “full frame.” This left no room for error and made each frame an expensive press of the shutter. 35mm was already standardised at 36 frames per roll and it was difficult to ignore such an advantage in terms of bang for your buck.

When pursuing this goal of making ever smaller pocket or travel cameras, manufacturers knew from history that they could not simply reduce the size of the film or frame size and still get acceptable results. To compound the issue, physics starts to get in the way of how easy it is to focus a circle of light of an appropriate size on a full width 35mm film frame. If the film cannot be made smaller, and the lens would be difficult to make for a full frame on 35mm, what do you do?

You make a half frame camera.

This was the exact conclusion that Olympus came to when they developed their extraordinarily successful PEN half frame cameras. Other brands caught on, but few really persisted with the idea other than Olympus and later Canon.

Buying Within Reason

Ten years ago, an Olympus PEN would’ve set you back about £10. These days they are anything from £30 in “unknown” condition to £60 upwards for working models. Although a PEN is the authentic, original half frame experience, it wasn’t what I was after. The selenium meters really put me off these types of camera, they’re prone to failure and don’t like being out in the open longer than they need to be.

I don’t think you need to be a genius to work out that I have an affinity for Canon equipment, so I turned to their line of half frame “Demi” cameras, because using French words in marketing is exotic.

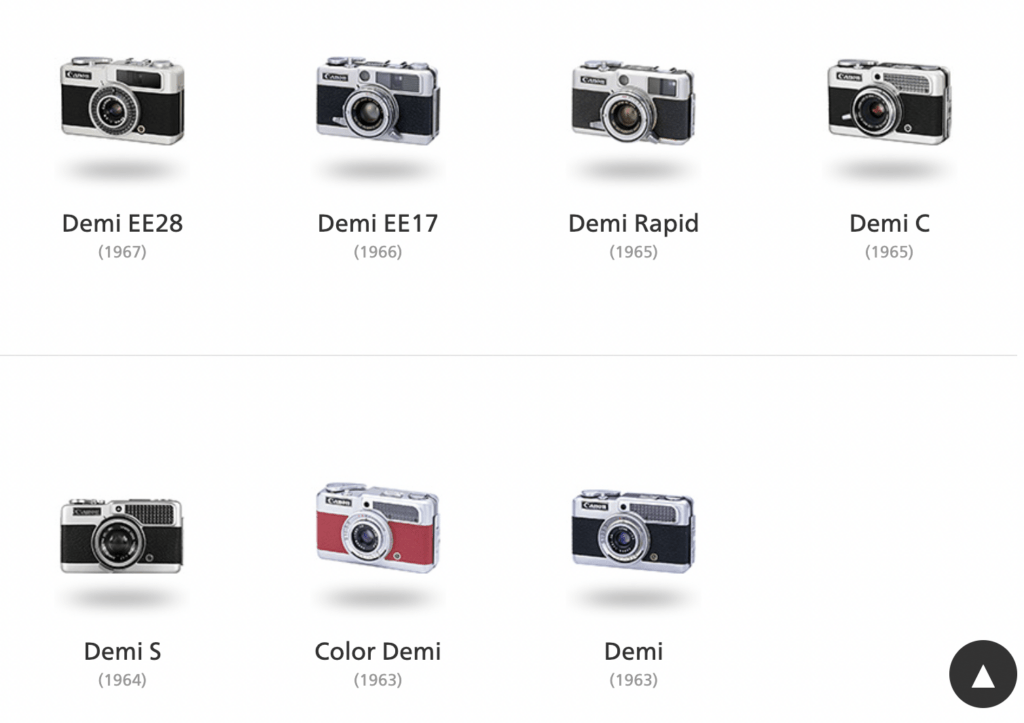

Canon released several models in the Demi line, but were very similar in their design and features. they made heavy use of selenium cell meters, offered more control than the PEN in terms of aperture and focus but little else. These were meant to be the ultimate pocket cameras and as automatic as possible.

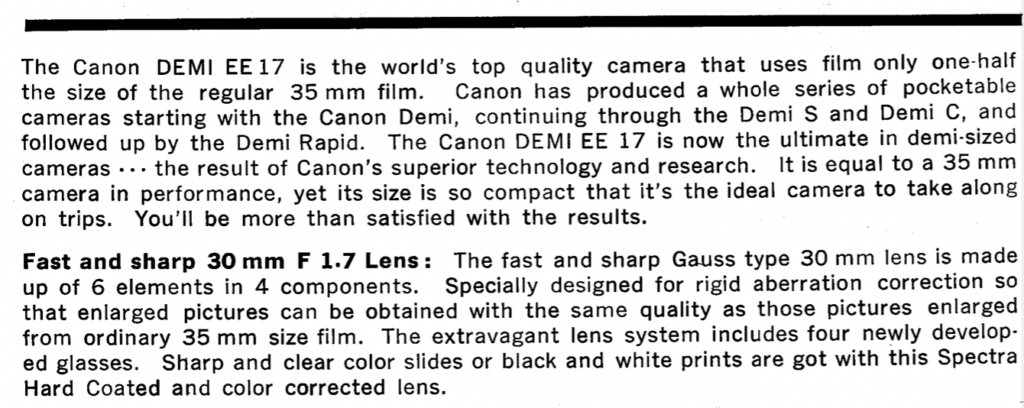

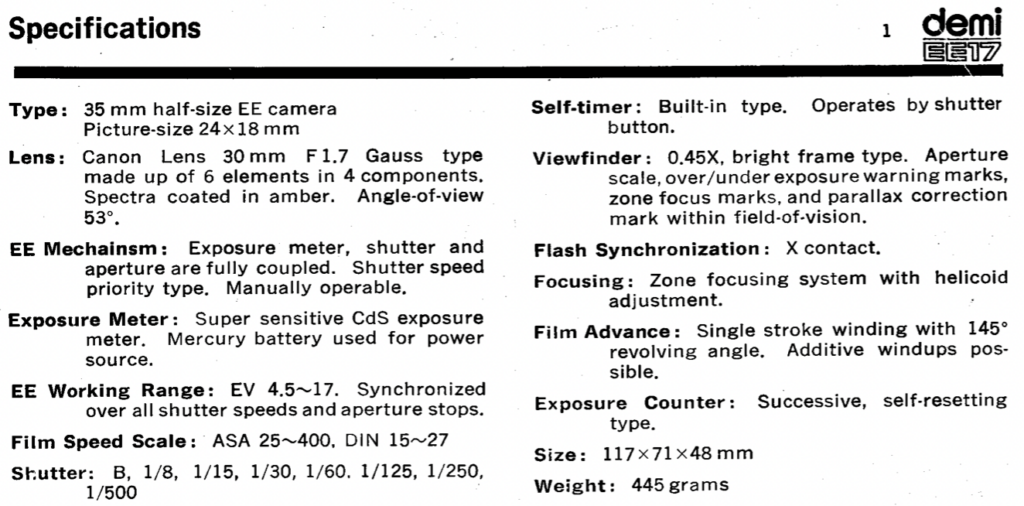

The EE17 was the top of the range model and offered reliable and accurate metering from a battery powered cadmium sulfide (CdS cell) photoresistor, the confusingly named EE28 was actually far less capable. The EE17 seemed like a cross between a range finder and a true automatic compact, featuring a smooth lens mounted focus lever, self timer and a “data finder” viewfinder that is surprisingly large, clear and a definite improvement of the Olympus PEN experience.

I’ve discussed before that one of the joys of shooting film is that it gives you the opportunity to try out the best of what the genre had to offer years ago at rock bottom prices. These half frame cameras are tipping into “retro-cool” territory and prices are rising. If you want a basic model with selenium meter you can still pick one up for £20-30, but if you want the best then get your wallet out because a Demi EE-17 in working condition is beginning to push £100 and thats just way too much.

I really wanted a Demi EE-17, in my opinion they are an absolutely beautiful piece of design engineering. I love the rounded design, attention to detail, decent meter, focus control lever and proper film advance lever. I’d have bought a cheaper model if necessary, but I’d always have been a bit disappointed it wasn’t “the one.”

I spent a while looking at options from the usual suspects, but Ebay prices were just out of control for any kind of sensible budget and I was beginning to run out of money for new kit. Nearly all EE-17’s are based in Japan, perhaps due to their popularity over there. They are offering various models in very good condition but with shipping you’re well over £120 and then because we like paying tax, you’re likely to get stung with import duties upon arrival, so even buying a broken one to repair was out of the window.

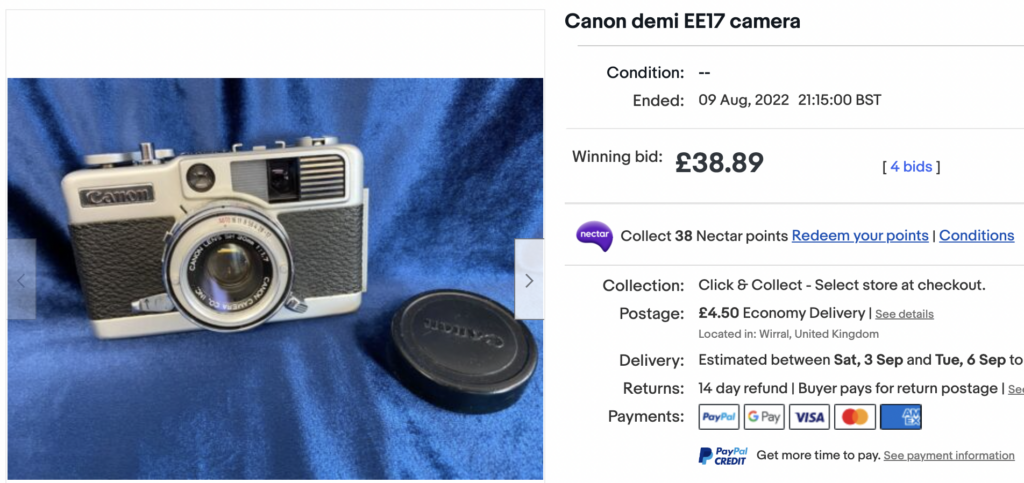

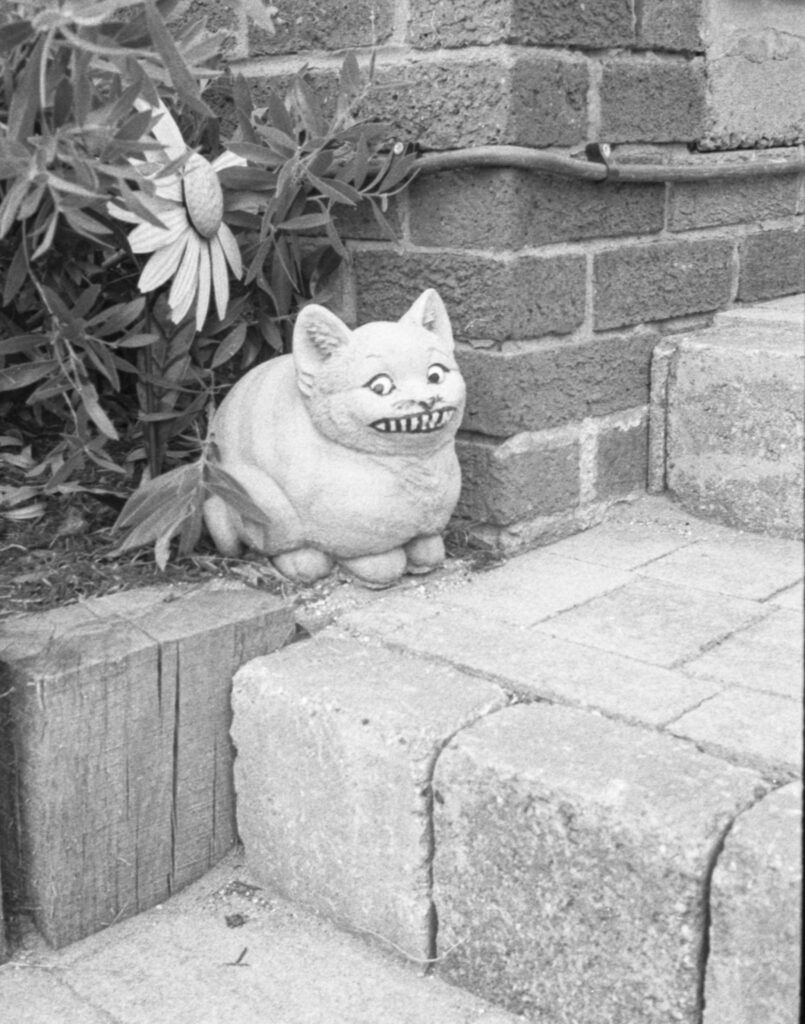

Just as I was contemplating giving up, this appeared:

This Demi was based in England, looked in excellent condition and was “untested” and we’ve discussed exactly what that means before.

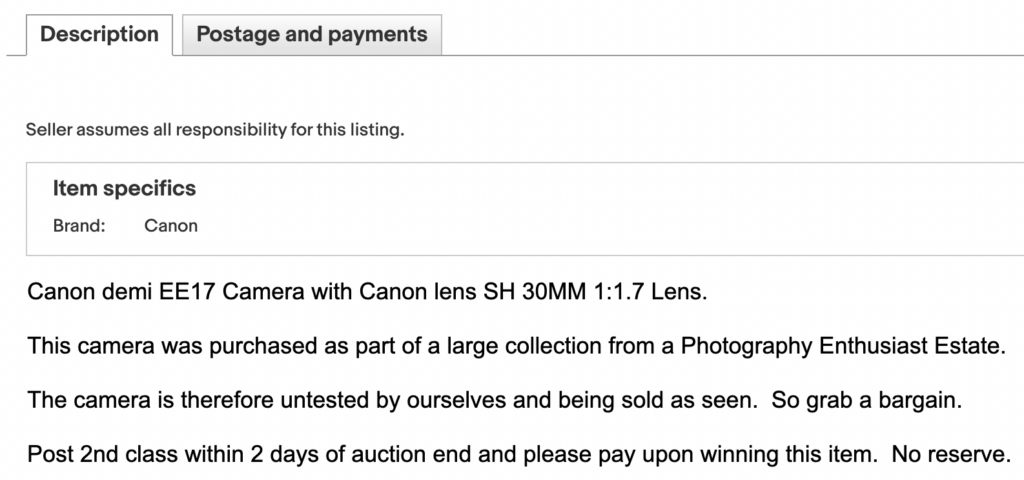

Looking closer made me err on the side of cautious optimism. The inclusion of the lens cap tells me that this camera really was well looked after by the previous owner. I cannot find another auction past or present where this has been included, it shows that someone actually cared about keeping things togther.

Digging into the sellers other items and feedback revealed they were not camera dealers and therefore were probably telling the truth in their description. The final piece of the puzzle is in the battery the EE-17 requires. You cannot simply stick a standard button cell in there and test whether the meter works, they were designed for the now illegal mercury 1.3v cells. To use this camera today requires a little metal adapter and the use of zinc-air hearing aid batteries. A non specialist seller is not going to bother going to those lengths to test out a light meter.

They should have, however, as despite some competition and nearly being outbid, I won this camera for £38.89. If this had been advertised as working, tested, you can guarantee that it would’ve tipped over £100 without too much of an issue, especially as it avoids importing. At nearly £40 this was almost double the amount I had in mind for what is effectively a toy camera in modern times, but in context it was cheap.

Upon receipt of the camera, I put a new battery in and it immediately came to life. Metering seemed accurate, the shutter speeds worked, everything looked and felt great. It’s even nicer in real life than in the pictures. Absolute score.

Features

For a half frame film camera from 1966, this has pretty much everything you could reasonably expect to find in such a compact form factor. The front of the body houses a really quite decent 30mm f1.7 lens, manual focus lever and scale, manual and automatic aperture settings, ISO setting and self timer.

The top is kept fairly simple with a very basic yet comfortable shutter release, film advance lever and film rewind crank. All appear to be made from aluminium.

That’s your lot in terms of externally visible features. Through the viewfinder you can see clear frame markings, the matchstick light meter and basic indication of the selected focus distance. What you won’t find is any indication of current shutter speed, although obviously the meter reacts as this is changed to show which F stop the camera will select, so effectively giving you a sort of aperture priority mode through the viewfinder.

It really is a very well made camera but it is badly in need of some kind of focus indication in the viewfinder. If you’ve ever used a rangefinder you will have experienced one of the various ways in which focus can be shown without being a TTL (Through The Lens) system. Moving the focus lever on the Demi does nothing for the user other than move a needle in the viewfinder across a face and towards a set of mountains, this is guesswork at best.

The problem is you’re looking through a bright, clear, crisp image in the viewfinder and it is so, so easy to forget that it is not the actual image being projected on to your film. I lost a number of shots by forgetting to focus at an estimated distance before the idea finally started to click in my head to check before each frame. This is so unnatural, though, as the whole camera screams “point and shoot” and you do use it with abandon, forgetting almost everything except for composure and pressing the shutter button. Canon could, and should, have implemented even a rudimentary visual focus aid in the Demi EE17.

Ergonomics and Handling

This is a wonderfully designed camera. Straight away you can pick it up and intuitively know how to use it. Once the ISO is set, there is almost nothing to it.

The Demi EE-17 fits nicely in the hand, the all aluminium construction makes it feel light weight yet solid and reliable. The controls are all in what seem like the right places and that makes it trivial to change focus distance or shutter speed whilst using the viewfinder.

The shutter release is really nicely engineered, weighted perfectly and responds decisively every time. Why do I mention this? I’ve also been shooting an Olympus PEN EE-2 side by side with the Demi EE17 and in comparison, the PEN shutter release is hideous. I’ve since serviced the PEN and it has dramatically improved but the build quality and feel is nowhere near the Canon.

Little things matter, especially in such a compact body, and this camera gives off the impression that a lot of thought and attention to detail went in to the design. As mentioned, the viewfinder is superb and the film advance lever is a real “nice to have” which again adds to the feeling of higher build quality than the winding wheel alternative on the Olympus.

Film loading and rewinding is a breeze, I am still reeling from the loss of over 70 shots on the PEN due to an incorrect film load. However, there is one slight issue with the Canon and that is the film door latch. It’s really not great.

The latch is an all external design, understandable considering the space restraints on a half frame body, but the catches are not deep enough to truly secure the door from being accidentally opened. There are no safety features on the release and simply clicking it down will pop the door open. At first I had at least three occurrences of the door magically opening itself whilst the camera was either in a pocket or a bag. I did take the body apart to fix the film counter and took the opportunity to lubricate and adjust the catch. It is definitely improved but still not to be trusted. A real shame considering the quality elsewhere.

Lens and Image Quality

Admittedly, I paid no attention whatsoever to the aperture the EE-17 selected for each frame. Usually I resorted to the highest shutter speed I could get (between 1/100 and 1/500) for every shot whilst balancing the meter somewhere in the middle of its range, which is between F5.6 and F8. At that aperture, the lens should be at the sharpest you’re going to get if the image is also in focus.

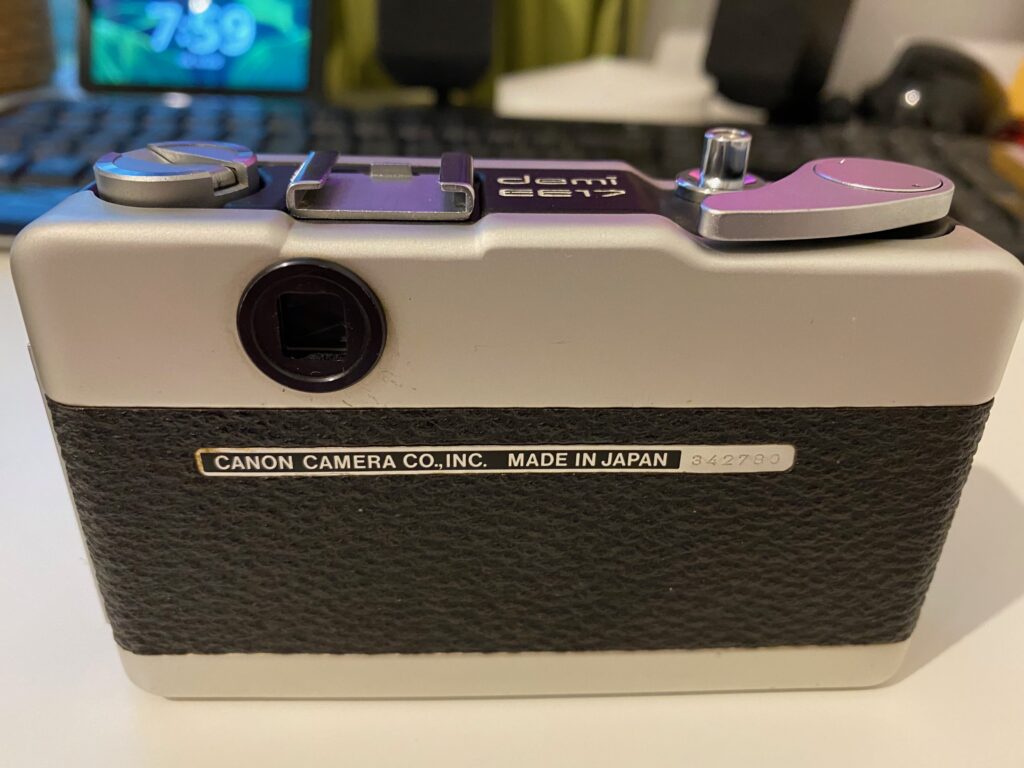

I think for a camera of this size the lens produces more than an acceptable level of detail and clarity. The limitations come from the physical reduction in the negative area used. When scanning half frame images at very high resolution the grain starts to become very apparent at anywhere over 50% zoom on a screen. Whether you like this grain aesthetic or not is obviously personal preference. I tend to try and avoid harsh grain where I can, I think there’s a time and place for when it adds something to a film image. There is often a risk that the grain becomes the image and you end up looking more at the texture it creates than the subject itself.

I didn’t expect miracles in terms of image quality from the Demi EE17 and in all honesty I’m quite pleased with how well some of the shots turned out. There is a definite learning curve in order to get the best out of this body, as there is with any new camera or film format you’re trying out for the first time. In future I’m going to stick a roll of ISO 100 through it and see what difference that makes in terms of grain in the final scans.

Conclusions and Learning

Roll the clock back to 1966. You’re offered a choice of a standard compact, a range finder or this half frame Demi. Which would you opt for?

Putting myself in the shoes of the 60’s photographer, that person who is looking for a camera to take family snaps, to record their holidays and not dominate days out then I think this must’ve been an incredibly tempting option. The ability to squeeze 72 frames out of each roll alone was a massive selling point and it would’ve meant no need to pack and fiddle with extra films on holidays and days away. Why, then, did it not really catch on as an idea?

The truth is that just as soon as the Demi and PEN range came to market, the prices of films continued to drop, as did the price of processing those films. This in turn began to impact the main sales pitch of the half frame compact – economy. Personally, I think the compromise of a smaller frame was a price worth paying back then for the sheer number of images you could fire off with abandon.

When I tested this EE-17 out I shot far more than I normally would with a film body of any type. It felt like the Demi set you free to take as many pictures, within reason, as you liked without having to worry about cost or running out. This, for film photography, is liberating.

There’s no getting away from the fact that half frame images don’t pack the same punch in terms of clarity, enlargement potential or overall resolution, but I think to dwell on these things is to miss the whole point of this type of camera.

I honestly feel like the Demi would’ve been the ultimate travel camera in the thick of the film era. If you wanted to use it as a device to document your adventures then it completely hits the nail on the head. The pictures this little thing creates are clear, workable and in the right circumstances, really high quality.

The Demi EE-17 really came in to its own on a trip to London. For street and “tourist” photography, I put it on to 1/250th shutter speed and just started firing off shots. Its diminutive stature means that people hardly notice you using it, you feel like you blend in to the background and for street – that’s a real selling point.

I had an absolute blast shooting the Demi and I will definitely be using it again. My only gripe is that you have to wait twice as long to finish off a roll and see your images! 24 exposure films are the sweet spot here.

Bottom line: if you can afford it, buy it. I love mine.

Share this post:

I have got one for £58 just couple weeks go. Fully working condition. Only issue I got with it is that I have no idea how to turn off exposure meter so it won’t drain battery.

You can’t turn the meter off, removing the battery is advisable when you don’t have a film in it or won’t be using it for a long time, this will also disable the meter. The battery will last at least a month or so in normal use, so if you take it out once you’ve exposed a roll you should see a bit more longevity. I use an adapter and zinc-air hearing aid batteries in bulk from Amazon, they’re very cheap.