A story of struggling against the passage of time, technology and endless rummaging in the garage for old computer parts…

This one is special, for me personally at least. A great deal has already been written about the Casio QV-10 and its various siblings, be it in reviews when it came out, websites when it was in popular use or as is the case now – retrospectively. This particular digital camera is widely regarded as a classic, simply because it was one of the very first consumer digital cameras. The QV-10 was competitively priced (for something so technologically advanced at the time) and superbly well designed and thought out. Whilst other cameras offered you a memory space of about 8 shots, Casio included enough memory to store 90 images before you’d need to engage in a marathon downloading session at your computer with a serial cable.

What’s the point in going over old ground, then? Certainly not for the image quality, performance or to test if it is some kind of modern day hidden gem. The truth is, I went out of my way to pick up a QV-10 just because it holds such strong personal memories for me. I was fortunate enough to spend my teenage years growing up through the bright, energetic, in your face technicolour of the 1990’s and as a consequence found myself in the first generation of young people who could record their lives in ways never before possible.

A friend’s dad had bought home a QV-10 from where he worked and although already out of date in 1998 when we got our hands on it, it still held up as something that was worth using to capture those endless summers, house parties and days out. Besides, it was all we had. That camera went everywhere, got lent out several times to various people and even found its way into our school on a couple of occasions. The pictures plastered our late 1990’s “home pages” as we made our first steps into the world of dial up internet. Thank God they now only exist on the Internet Archive, and only then if you know exactly what to look for – fortunately we were all sensible enough, even then, not to use any personally identifiable information online…

So, here we are at least 25 years later doing a retrospective that I’ve been looking forward to for years. I’ve always loved this camera and the journey to getting another has not been an easy one until a few months back when everything started falling into place completely by chance.

In this retrospective review:

- Did anyone ever take this seriously?

- Why buy a QV-10 now?

- Finding a relic

- Before you learn to shoot, you must first learn to build a Windows 3.11 machine…

- …and then rebuild it into a Windows 98 machine

- Rediscovering the joy and magic of digital imaging

- Better on the TV?

- Conclusions and learning

Did anyone ever take this seriously?

This might sound silly, but when digital cameras first came out people weren’t entirely sure what to do with them. Nor, for that matter, were the manufacturers. Marketing material took a scattergun approach of just listing all the possible use cases they could think of. Casio had quite a nice way of sharing this journey of discovery on their website in 1997, with a section that covered people describing how they were making use of the QV-10 in their day to day lives. Users ranged from university lecturers to scientists and even surgeons. These were published on a page called “The Casio Digital Camera at Work.” It sounds like something out of a rousing, motivational 1940’s public information film and should’ve had some kind of brass band music playing behind it for the full effect.

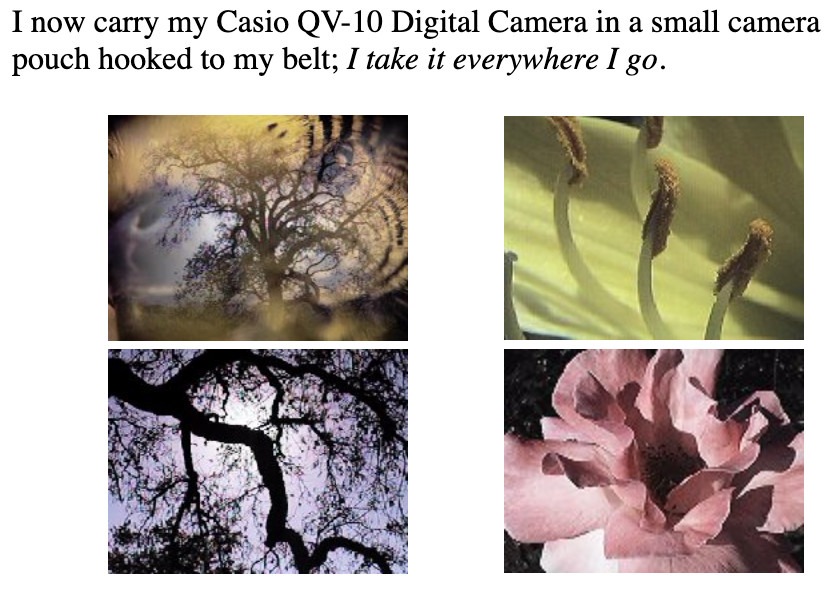

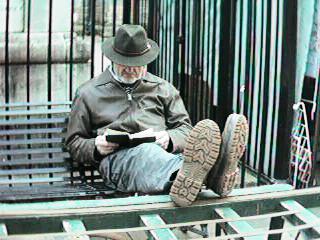

In fairness, the quality of the images these people managed to produce with a QV-10 is nothing short of remarkable. I won’t show you the sample images from the plastic surgeon because they are utterly stomach churning. Even at a resolution of 320*240 you can see all too clearly the inside of some poor sods thumb which is being sewn back together. Instead, have a look at how good Mr Pecoraro’s photos were. I’m genuinely impressed:

This meander through the Internet Archive is well worth the effort because at first glance you’d be forgiven for taking one look at a picture from the QV-10 and asking whether it is some kind of joke. There are £10 plastic children’s toy cameras available in charity shops which can give better results than this, but that’s comparing things to the standards we expect in 2023. In 1995, when this camera launched, it was nothing short of miraculous. Users would’ve been running screen resolutions of 640×480 on their DOS/Windows 3.11 machines and that means an upscaled Casio QV-10 image would have filled the screen and looked “not bad at all.” Certainly as a device to generate snapshots for websites, it was more than up to the job. No one was complaining about this camera in its day.

Why buy a QV-10 now?

As some of you will know, I’d recently made the mistake of browsing through some old images in my archive of pictures. This started a very predictable journey down the eBay rabbit hole of “just checking” how much these old cameras I’d used previously were selling for now. After discovering the Fujifilm A201 was selling for all of £5 and the far, far superior Olympus C860-L was similarly priced, purchases and reviews were an inevitability.

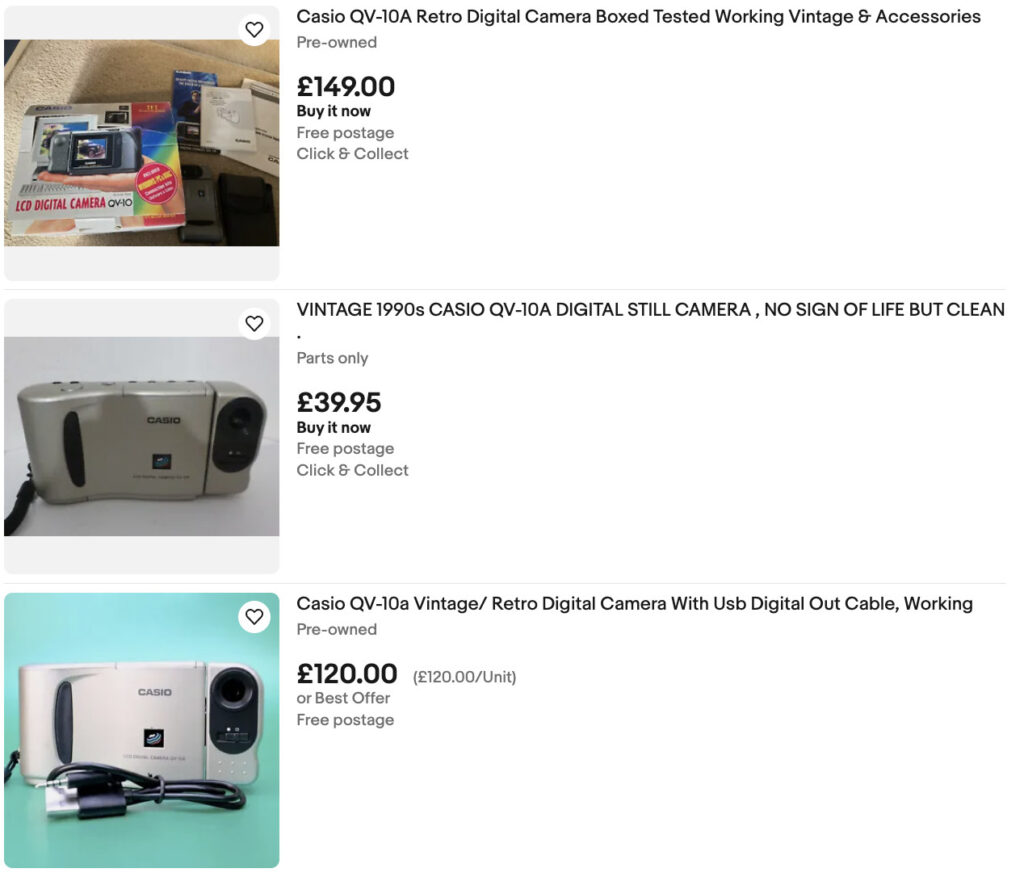

At the same time, I’d looked up the Casio QV-10 and prices were eye watering. I mean really, really silly. Take a look at the current state of the market as of December 2023:

Broken? That’ll be £40! Oh, you want a working one? That’s one hundred and twenty quid. But that’s not all, the “usb digital out cable” is a complete waste of time – this categorically will not work with the QV-10, not unless you’re prepared to write your own software for it at any rate. Boxed? That’ll be another £30. Prices were in the utterly absurd range and the dream of picking one up to write this very article was dashed.

I set up an eBay email alert on the off chance that someone might list one for a sensible price. In reality, I’d planned to go down the route of waiting to find the cheapest broken QV-10 that had at least some of the bits and pieces with it that I’d need and then attempting a repair on whatever the issue turned out to be. This seemed to be the most cost effective and likely way I’d be able to afford one in the current market.

Email alerts rolled in every few days, but weeks rolled by with nothing coming up that was cheap and broken or working but sensibly priced. I held back, determined not to get carried away and tempted into spending money I really didn’t have on yet another trip down memory (card) lane.

|  |

| Same shot, same camera… | …24 years apart |

Finding a relic

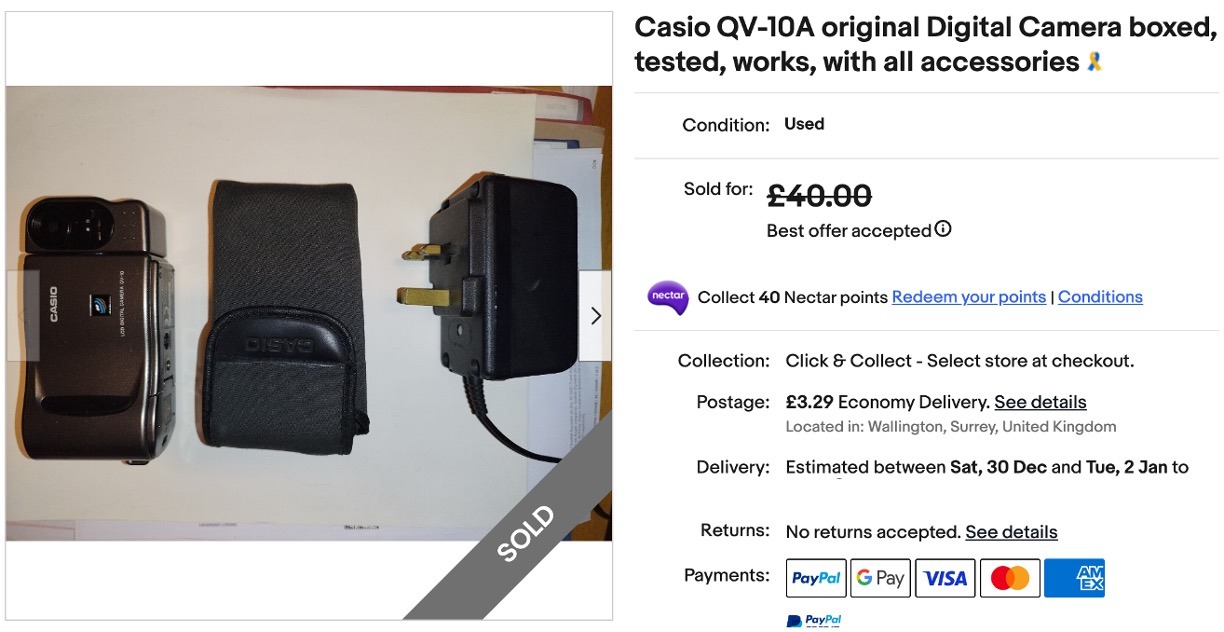

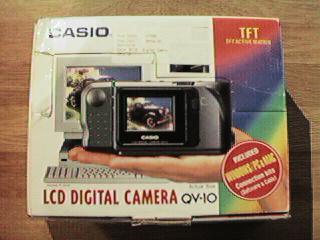

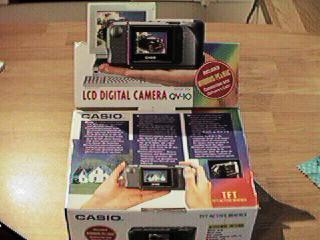

Then it happened – an alert popped up for a new listing that I hadn’t seen before and the price was high, but not ridiculous. I half expected it to be a “parts or not working” auction at first but a quick read of the description revealed that this wasn’t just working but boxed with everything it originally came with.

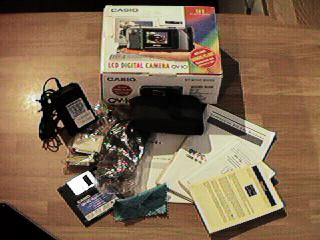

I think it’s important to point out that the QV-10 isn’t a camera that you can just buy as a body and that’s it – you’re ready to go. The memory is soldered to the board in the camera and the only way of retrieving the images is through a proprietary Casio cable and equally proprietary software which talks to the camera. Without these, you’re practically buying a digital brick. The Internet Archive has copies of the software, so that’s not too bad, but the cables are a DIY job these days.

I immediately put in a £30 offer to test the waters and see how highly the seller valued their camera. My eyes nearly fell out of my head when an email appeared ten minutes later saying “offer accepted.” Things only got better from then.

The auction photos did not do this thing justice and I think that’s a large part of the reason why it didn’t attract more interest before I put my offer in. The original listing was fairly lacklustre in terms of showing off what you were really getting, but what arrived was genuinely amazing. The camera arrived in its original box, with the original packaging (down to the little bags everything came wrapped in) and every last cable, bit of documentation and even the tiny cleaning cloth that was included for polishing up the lens.

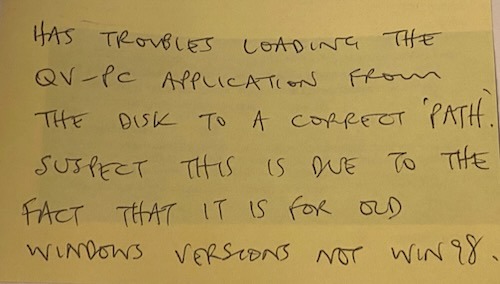

Furthermore, the original owner was either the most wonderfully careful person in the world, or they didn’t use this much at all. The camera itself is in as close to new condition as it would be reasonable to expect a 25 year old, second hand camera to be. Inside the various manuals were little hand written notes that document some of the trouble I think they must’ve had getting this set up – their Windows 98 computer had apparently conflicted with the software at some point, leading them to believe it was too new for the ancient Windows 3.11 software to handle. Having used one in the 90’s with Windows 98, I knew there was definitely a way of getting it working.

For the life of me, I can’t figure out why they had trouble with the software. The disc worked perfectly (the first thing I did was to take an image of it just in case it died) and it was happy to install on operating systems as late as Windows XP. For me, the application wasn’t the problem – finding a serial port that will actually talk to this thing… Well, that’s another matter entirely.

Before you learn to shoot, you must first learn to build a Windows 3.11 machine…

How do I know that QV-Link will run on Windows XP? The answer is, being the sad git I am, I happened to have a Pentium 3 450 machine already built, sat in the garage waiting for something to do. The OS I’d last used on it was indeed XP and the machine to all intents and purposes fitted the bill. It has a serial port built in to the motherboard (unusual for a machine as “late” as a Pentium 3) which is the key prerequisite for a PC that will talk to a QV-10 and its special cable. I promptly fired it up, installed the software and got all carried away when it ran perfectly without any issues. I then plugged the camera into the serial port and… nothing.

To save you from what in reality was about an hour of changing every setting in the BIOS and even doing a quick bit of learning about serial standards, ports and how they work just in case I’d missed something – I’ll just conclude by saying the motherboard was too new for the QV-10 to work with it. My best guess as to why is that at some point when serial ports were being phased out, manufacturers started to control more and more legacy hardware in either software or dedicated all in one controllers that didn’t quite implement all of the various legacy standards properly. Consequently, the search was on for an alternative.

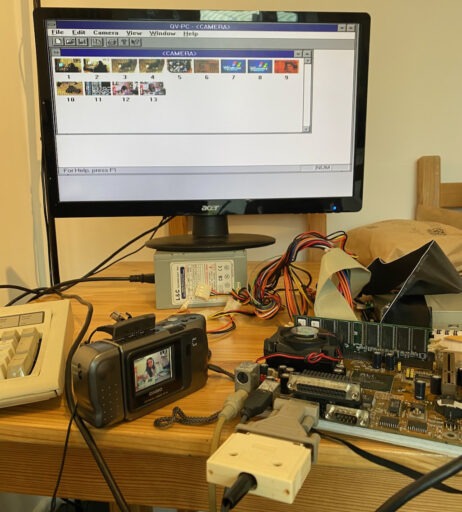

Initially, I tried an old IBM P133 board that had been sat in storage for some time, but that promptly killed itself and left me with one final board to try. I know, you’re shocked that I don’t have endless boxes of old computer components lying around… I bodged together a test system that comprised a socket 7 board, the P133 out of the old IBM and a whopping 2mb PCI graphics card. The idea was to build the oldest machine I could in the name of compatibility. The QV-10 software was designed for Windows 3.11 and the manual goes to great lengths to tell you that it is neither tested nor officially compatible with Windows 95, let alone 98 or later.

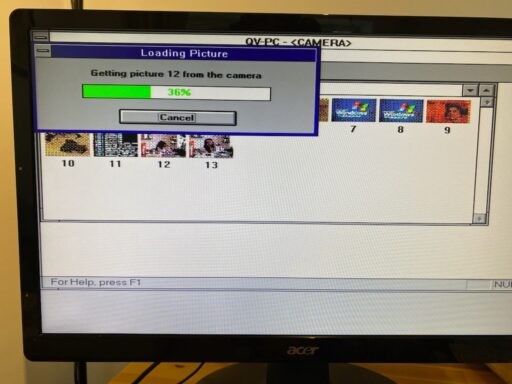

After an entire morning of mashing together various old components, finding enough floppy disks to write Windows 3.11 to, discovering I also needed to write DOS 6.2 disks, then installing these two operating systems one after the other I finally had a system that booted Windows 3.11. With a great deal of trepidation, I installed QV-Link again and attached the camera. To my great relief (and slight disbelief) it worked. I couldn’t believe my luck!

This was it! The final piece of the puzzle was complete. I could now use the QV-10 and successfully download the pictures from it without any problems whatsoever. Surely, then, it was time to go out and take some pictures? Well… no. I had one final hurdle to overcome and that is the small problem of getting the pictures off this machine to use anywhere else. I could have just removed the hard drive and plugged it in to a dock every time I wanted to share the images, but that was a complete faff and would also mean I couldn’t realistically build the machine into a case to get my kitchen table back. Furthermore, I’m not sure the hard drive would put up with being plugged in and out of things repeatedly – it wasn’t in the best of shape anyway.

The answer was either going to have to be networking or some form of external storage. USB, however, was a pipe dream when Windows 3.11 was released and even Windows 95 doesn’t really understand it – and it certainly doesn’t play with USB storage devices. Networking was so far removed from the standards used today that wasn’t going to work either. The only way to sensibly do this was to upgrade the operating system to something a bit “newer.”

Sigh.

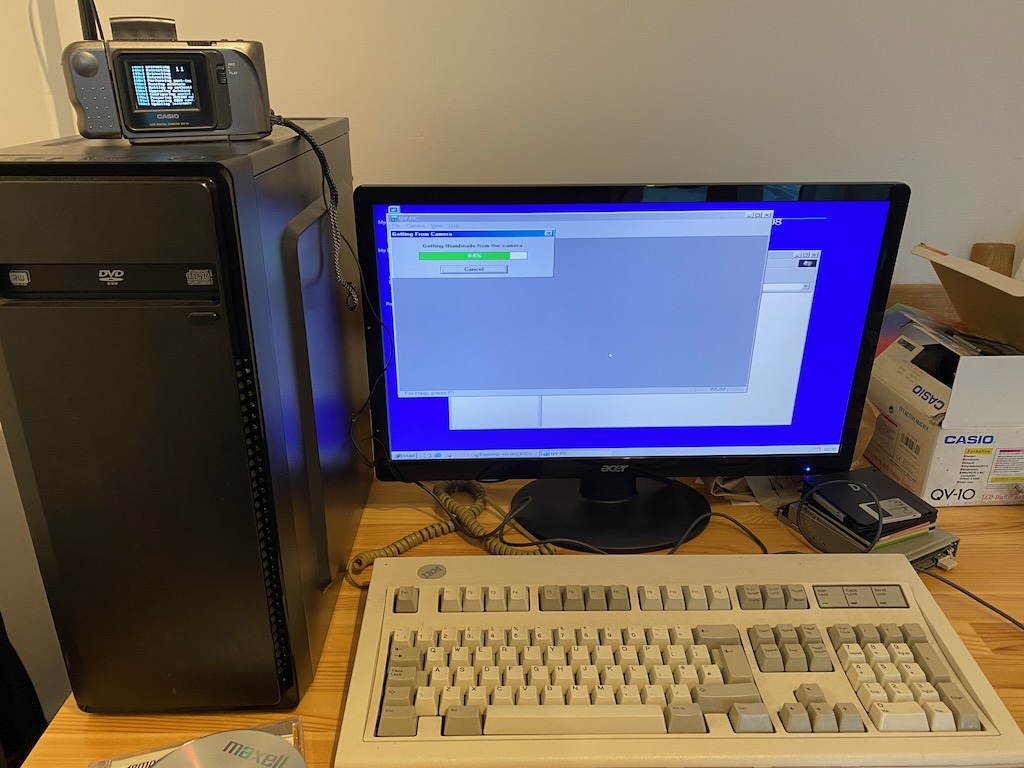

…and then rebuild it into a Windows 98 machine

The upgrade was pretty much painless, just time consuming and a reminder of how long everything used to take on slower processors and even slower methods of storage. Again, for the sake of your sanity and mine, another long story shall be cut short. I somehow managed to upgrade to Windows 98 First Edition. Does this really matter? Yes. Yes it does, because the drivers that make USB drives work point blank refuse to install, so yet another install later using the Windows 98 Second Edition CD saw me finally arrive at a working set up where I could download images and transfer them over to newer machines to use.

The final end of the computing road, then?

Of course not!

You see, Casio in their infinite wisdom decided to make a very subtle variation of the JPG format for their digital cameras and call it .CAM. These CAM files are effectively JPG images with a header file containing meta data that would these days be stored as EXIF. The problem now is that absolutely no imaging software supports CAM, and why would they – it’s been dead for nearly 20 years.

I needed a method of converting .CAM images to .JPG in batches. I knew this was possible as, once again, I remembered doing it to hundreds of these images back in 1998/1999. The confusing thing was that the QV-Link software doesn’t have the capability built in – it was either CAM, TIFF or BMP. It seemed a bit silly to go through two conversion processes so I looked into conversion software.

Once again, a few hours were lost to various websites and a serious dig in the Internet Archive. This batch conversion problem was definitely something that was an issue for original users of the QV-10 and a few enterprising individuals had written conversion utilities. I went through them all and they either refused to work, didn’t recognise this particular version of the CAM format or, in the case of one utility I found, just decided to completely change the aspect ratio of the images and expand them 2x horizontally for no reason at all.

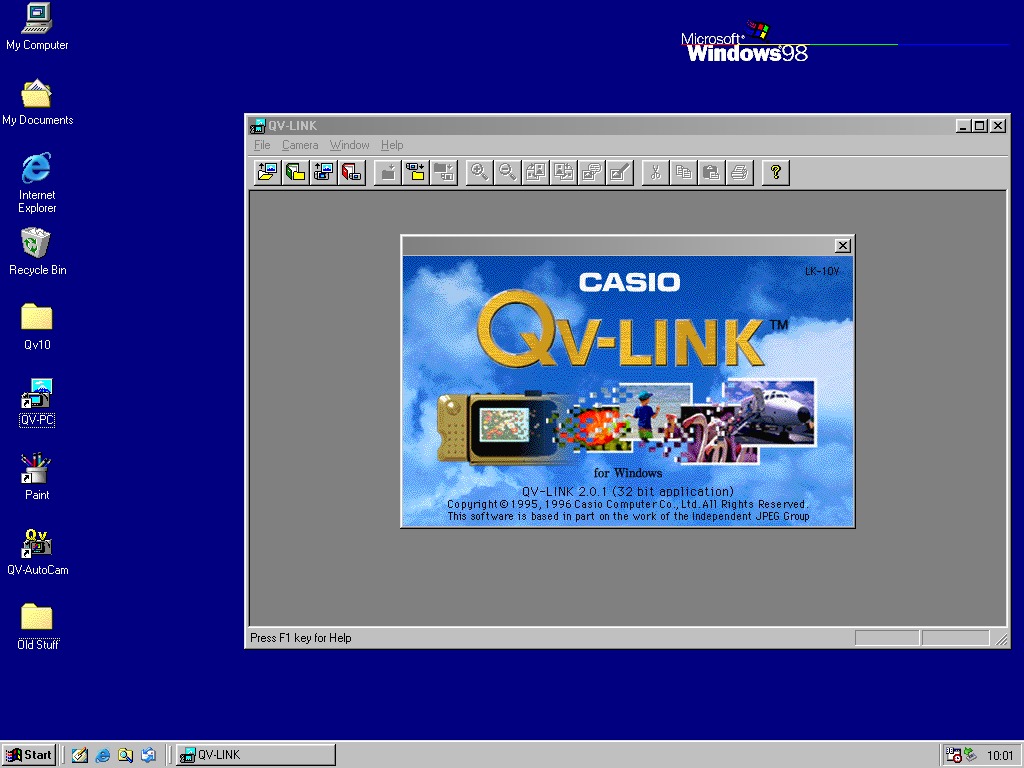

The really, really, really frustrating thing about this whole experience is that I’d looked at newer versions of QV-Link, down to even reading the manuals and at no point, nowhere did anything even mention batch JPG conversion capabilities. I was growing more and more frustrated, knowing I’d done this years earlier and convincing myself that I must’ve had some long forgotten utility to do it with. As a last resort, I downloaded version 2 of the QV-Link program from the Internet Archive and installed that. What happened next? You can already guess.

Why, Casio? Why did you not mention this in the upgrade notes? The manual? On your website? Anywhere?! More to the point, why did no one who owned this camera in the 90’s think to just mention the fact that this bulk conversion was built right in to version 2 of the software that comes with the camera?! So many people were asking, searching for the same thing yet not one site makes any mention of it.

So, if anyone out there in Internet land just happens to buy their own QV-10 and wants to bulk convert or batch convert .CAM to .JPG – I’m here to save you a world of pain, boredom and frustration, just download QV-Link 2.0.

Were we done now, though? Yes. Finally – we can actually do what we came here for – early digital photography. If ever you think computers and technology are annoying today, just wind the clock back 20 years and you’ll be begging for the future back within about five minutes.

Rediscovering the joy and magic of digital imaging

Upon first picking up the QV-10 again I was struck by just how light it is. Without batteries the camera weighs about the same as a couple of pencils, it’s not what I expected or remembered at all. Putting batteries in instantly balances out the camera and gives it that necessary weight that makes it feel more secure and sturdy in your hands. This isn’t a matter of build quality, nothing about the QV-10 feels flimsy although following recent experiences with old plastics I’ve been overly cautious every time I open the battery door or close it with a wince every time the clip snaps shut. Touch wood, so far it hasn’t broken.

For such an early camera, Casio got so much of the design right. Remember, this is a camera that came out in 1995 and had a swivel round “selfie” lens system. If that isn’t one of the greatest examples of being ahead of your time, then I don’t know what is. The swivel lens isn’t just useful for selfies, it’s actually a really great usability feature in itself. Think about modern cameras with their tilty-flippy screens, this is just the opposite of that – instead of moving the screen, we just move the lens around and that definitely makes shooting high or low down subjects an absolute piece of cake.

Moreover, the performance is genuinely good. The LCD screen on the back has a relatively slow update but it isn’t so slow as to make it useless or jarring in any way and again, in context of its launch date, its performance is decent. Held at the right angle, and viewing angle is critical, the screen does give a very accurate representation of the image you are going to get when you press the shutter or later download the image off the camera.

Talking of the shutter, picture taking is practically instant due to the fact there is no focussing other than a rudimentary macro switch on the side. As a side note, the macro switch does make a large and noticeable difference for close up shots. Close up shots are something you’re going to want to do a lot with this camera because it is one of the few ways to maximise what little resolution there is for resolving detail of any kind.

When the shutter is pressed, the image is taken without delay but then you do have to wait approximately 2-3 seconds whilst that image is then written to the internal storage. The camera is locked out whilst you do this and I found out by accident that even the power switch is ignored until the data is written. I did panic after one shot that I’d flicked the power off mid-write and the picture would be lost but the camera is intelligent enough to wait and then shut down.

This is genuinely something to worry about because the manual and a separate yellow page included in the box, do both tell you that if you lose power or somehow mess up the writing of data to the internal memory, you will effectively brick the camera. I did read anecdotally that this is something Casio addressed in later revisions of the QV-10 in that you could at least hold down a combination of buttons to reset the memory, but this isn’t something covered in the manual and Archive.org was full of people stating they’d had to send their cameras back to Casio after getting the dreaded memory error. As one user commented, this is a very stupid design.

I wholeheartedly love using this camera. I couldn’t care less that the resolution is pitiful and the pictures practically unusable on todays websites, displays and so forth. It just doesn’t matter. It’s more fun than the Fujifilm A201 I went back to recently and it’s just a lovely, tactile piece of technology history that’s a great talking point today.

Better on the TV?

I bet you thought I’d finished talking technology, didn’t you? In all honesty, I had until I read an old review someone had written about the QV-10. The camera comes with both a data port for sending images to your computer and a “digital” port for sending pictures to any TV which has a composite in socket. The reviewer claimed, with images to prove it, that the camera gave visibly better image quality when displayed on a TV than when sent across the data cable to a PC.

This, they said, was because the camera is applying a high level of JPG compression to the images before they are transmitted but… I find this hard to believe because the compression is applied before/as the image is stored in the camera and not before or as it is transmitted from storage to the PC. However, I couldn’t argue that there was a difference in the review image comparison provided on this site.

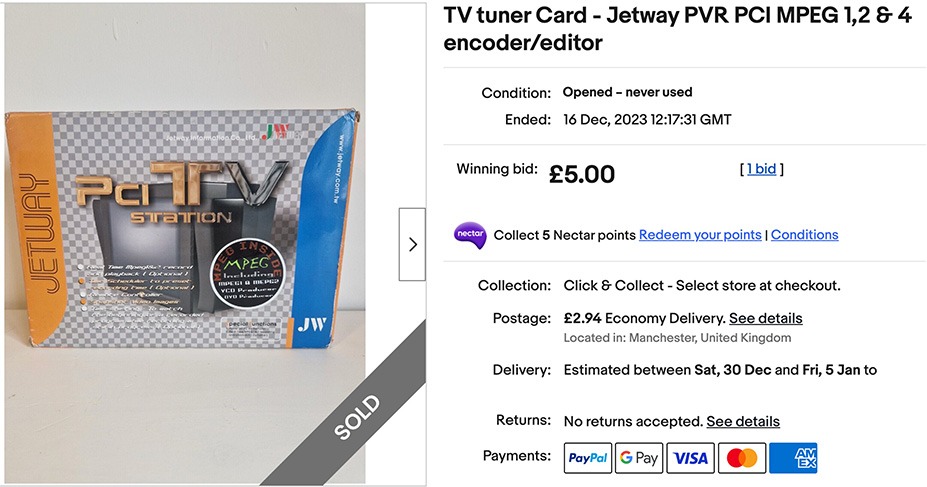

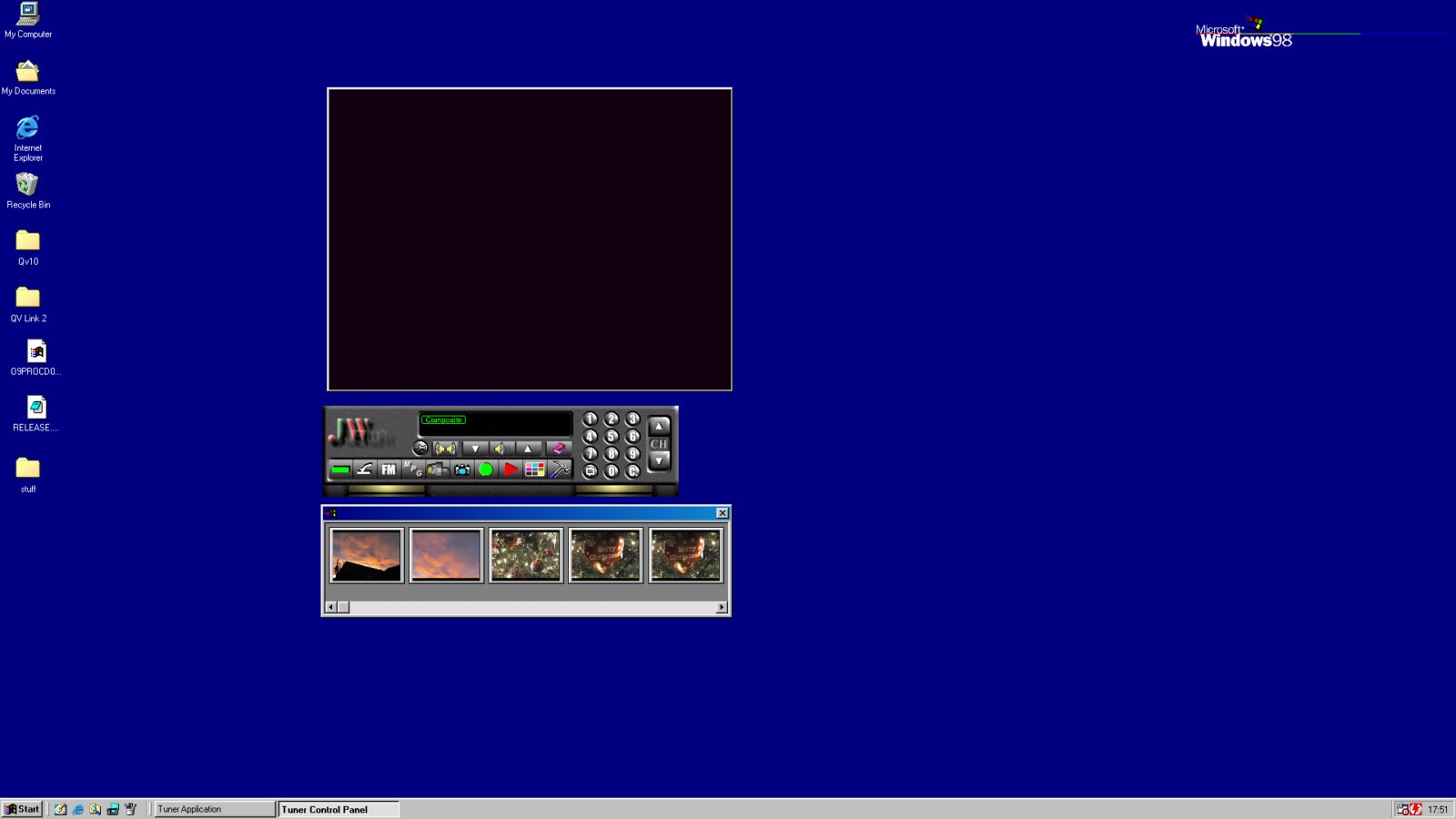

When working with images of 320×240 pixels, anything you can do to improve the image quality is worth a try. There was only one way to sensibly try this out and that was to buy a TV card with an AV/Composite in port and take direct screen captures from the card. TV cards shouldn’t apply any compression to the images it displays and should give a reasonably faithful representation of the signal it receives – especially an older TV card designed to run on period correct hardware as there simply wouldn’t have been the processing resources available to do any kind of serious image manipulation without introducing obvious delay.

You know what this means, don’t you. It’s eBay time again.

There’s no long story here – the whole process was refreshingly straight forward. Shockingly, the market for analogue TV cards suitable for Windows 98 machines is basically nonexistent and so I found a boxed example with all original accessories and, most importantly, drivers included for £7.94 all in.

The card arrived within a few days and worked perfectly first try. The software provided was basic but completely adequate for the purpose I needed. It picked the camera up as soon as I turned it on and it was quite fun to see the images appearing live as I changed the pages using the buttons on the camera. The software has a built in screenshot button that then captures a number of frames and allows you to choose the type of file output you want afterwards.

Fun though it was, the results of this experiment were something of a let down. I took screen captures of a number of sample images and placed them side by side with the .CAM imports from the data cable. Unlike the review I’d read, I obtained the exact opposite in my results. I think it is quite clear that the captures from the TV card are obviously less sharp and detailed than those from the camera itself.

|  |

| QV-Link Import | TV card capture |

Is this conclusive evidence? No, of course not, but I don’t personally find it surprising. As previously mentioned, the compression has already been applied. Converting the image then into a composite signal can only introduce more degradation rather than improving things. Unfortunately, I can’t find the page I read this on again – a classic case of having so many tabs open during research and then closing them all before bookmarking the ones that might be useful in future. If I could, I’d have another look at their method of image capture to see what they did differently, but as it stands I don’t know how else I could improve the capture of the image from the camera digitally. Perhaps a modern TV card would make a better shot of it?

Conclusions and learning

Fun. That’s the word to describe this camera. The sheer joy this must’ve been to use by the early adopters in 1995 is plain to see – the magic of just being able to click away and instantly see a picture in a world dominated by film photography would’ve felt like you were holding the future in your hands – and that’s exactly what you were doing.

Considering the launch date, it took other manufacturers several years to catch up, not only in terms of image quality but also the design and ease of use. I stated earlier that Casio really nailed the design straight away with the QV-10 and they absolutely did. Considering how horrible some early digital cameras are to use and how bad some of the user interface design was, the Casio is refreshingly simple, quick and easy to use. You do not need to read the manual to work out how it works and the screen remains uncluttered no matter what mode you are shooting in.

Downloading images is a slow process, even by 1998 standards, but not painfully so. The software is largely garbage – a deliberate attempt to force you to use their method of organising albums and even Casio themselves realised relatively quickly that proprietary image formats were a bad idea when your biggest target market are people who wanted to make websites. Back then, it was GIF, JPG or nothing at all so you can imagine that most users of the QV-10 converted everything to JPG.

I may not have heavily used the camera in any one particular session, but battery life was appreciably better than some later cameras I’ve used. I mention again the Fuji A201 here because for a camera 5/6 years newer, it has the most appalling battery life I’ve ever known in a camera. I’m aware that in the 1990’s, batteries were not as good as they are now, but even testing both with modern batteries, the Casio lasts long enough that you don’t worry about running out. This is actually one key advantage of these early cameras, the fact they use AA batteries is a real boon to the retrospective reviewer. Not only do we benefit from modern rechargeable battery technology, you’re not wrestling with proprietary chargers and poor battery life as I found in the recent Canon S10 review. There’s a lot to be said for the convenience and availability of standard formats!

As I found when reviewing the Canon T90, if you go far enough back you can see all these little threads that run through design history that still have an influence in todays machines. Casio, whether they knew it or not, created a number of brilliant features on their first digital camera. The swivel lens, we’ve mentioned, but the introduction of a live view screen was truly novel and is now ubiquitous. They knew the importance of decent ergonomics, handling and just how much it matters to have a clear, concise user interface that can be used by anyone. If only they’d understood how significant removable storage was going to be, but in all fairness in 1995 the market was primitive at best and thank God they didn’t go down the Sony route of bolting a camera on top of a floppy disc drive and calling it innovation.

There’s only one downside that is specific to the Casio and it’s the use of internal memory. This forces you to use the data cable supplied and as I painfully found out, that also forces you to use period correct hardware. I’m sure that with enough hardware expertise, you could probably find a way to make this work with USB on a modern computer – but that’s beyond me and probably beyond most people who care enough to put the effort in to reverse engineer either the cable, the camera protocol or both. The outcome of this is that, no matter how good condition my camera is in, there will come a day in the future where it will no longer be usable due to there being a total lack of working hardware to plug it in to. I consider myself fortunate that I just happened to have a few boxes of old tat in the garage that could coax it into life and get it talking to the computer.

I love the QV-10, it means a lot to me and although I could genuinely cash in on this one in the current eBay market, I can’t bring myself to. I don’t really collect cameras, instead I tend to buy them, write about them and then pass them on to a good home, but this is one camera I can’t bring myself to part with. It’s too much a part of my personal photography history and I’d like to think that every now and again I’ll crack it out for either some kind of assignment, to remind myself just how bad (good) things used to be or simply just to enjoy that swivel lens, low resolution, early digital nonsense for no reason other than… it just makes me smile.

Good times. Thanks, Casio.

Share this post:

There is a current program called GraphicConverter that supports CAM files, made by Lemke Software.

35 Euros! Hmm…. I think using the Casio software in a VM to bulk export to JPG would be the way to go!

Thanks for the info!