I’ve written before about my camera firsts – the Casio QV10 was the first digital camera I ever used, Fujifilm’s A201 was the first digital camera I bought myself. My preference for Canon gear began with the Ixus 500 before my first ever DSLR in the form of the Canon 350D. My first film SLR was the Canon AE-1 Program. You’d be forgiven, therefore, for thinking that not only is that a lot of firsts, but that I’ve surely covered them all by now. Well, not quite. There’s one first that I’ve neglected until now and that is… the very first.

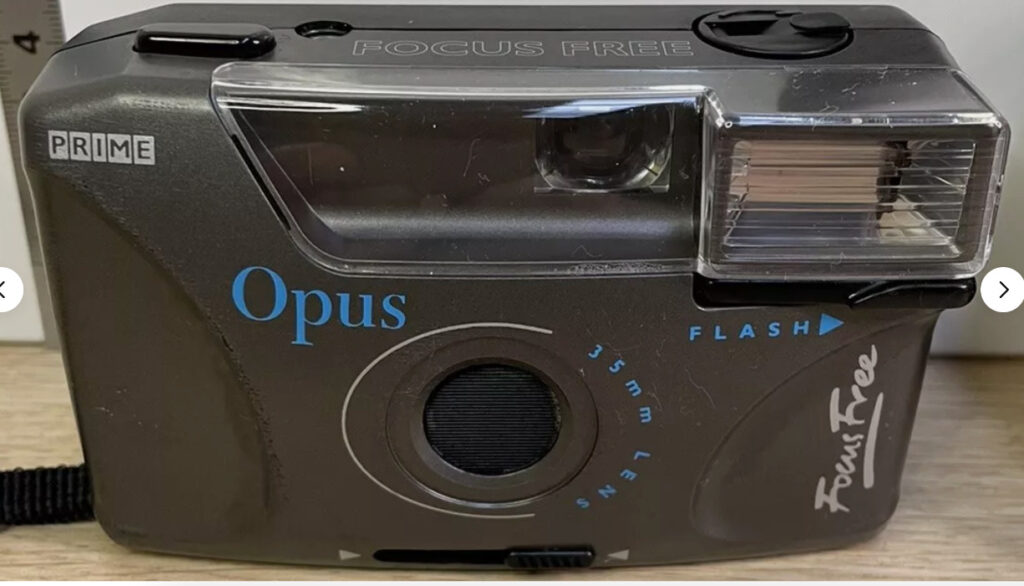

The very first camera I ever owned and ran a roll of film through was the least flashy, least expensive and most feature free camera you could imagine – an Opus Prime. Finding one again after all this time has been difficult to say the least, mainly due to the fact I couldn’t for the life of me remember what it was. All I could remember was that it had been grey and had a flash. Trying to find that amongst the thousands of different models which tick those two boxes is a futile exercise at best, but fortunately I had one more key piece of information at my disposal. I was convinced that I could remember going in to a branch of SupaSnapS (yes, they capitalised the last S for some reason in the 80’s but dropped it later) to buy it.

So began a long, long search.

In this post:

The search begins

SupaSnaps were a national chain of development and print labs, usually with small shop fronts that sold the accessories you’d expect – cheap frames, photo albums and a limited range of cameras. I must admit that I don’t remember a great deal about them other than they were local, convenient and must’ve processed a reasonable amount of films for my father because I can vividly remember being given several of their giveaway “Snappit” cameras. This must’ve been circa 1991, 126 cartridge film was being discontinued and the free Snappit camera was an effort to sell off their remaining stock and encourage people to bring it back in for developing. I know for a fact I never put a roll through one but they seemed extremely cool because they were wonderful bright colours and impossibly small. I’m sure they made a fortune from children smashing out frame after frame on these cameras.

We’re going to come back to the Snappit in a future episode because they’re well worth a look in their own right and, believe it or not, 126 film has started production again. The analogue photography resurrection truly is something to behold.

The problem with my camera having been retailed in Supasnaps is that if you Google “Supasnaps camera” you get nothing but the Snappit. The other problem was that because I couldn’t remember the brand name of the camera and they hadn’t branded them “Supasnaps” cameras, I couldn’t just search for all cameras by a specific make and go from there. In 1990, there were four places you would have bought a camera on the local high street. These were Jessops, Argos, Dixons or photo labs like Boots or… Supasnaps. I was convinced it definitely wasn’t a Jessops or Dixons camera, so began by searching through old Argos catalogues to see if anything jogged my memory. This plan worked spectacularly when I came across the Halina Vision.

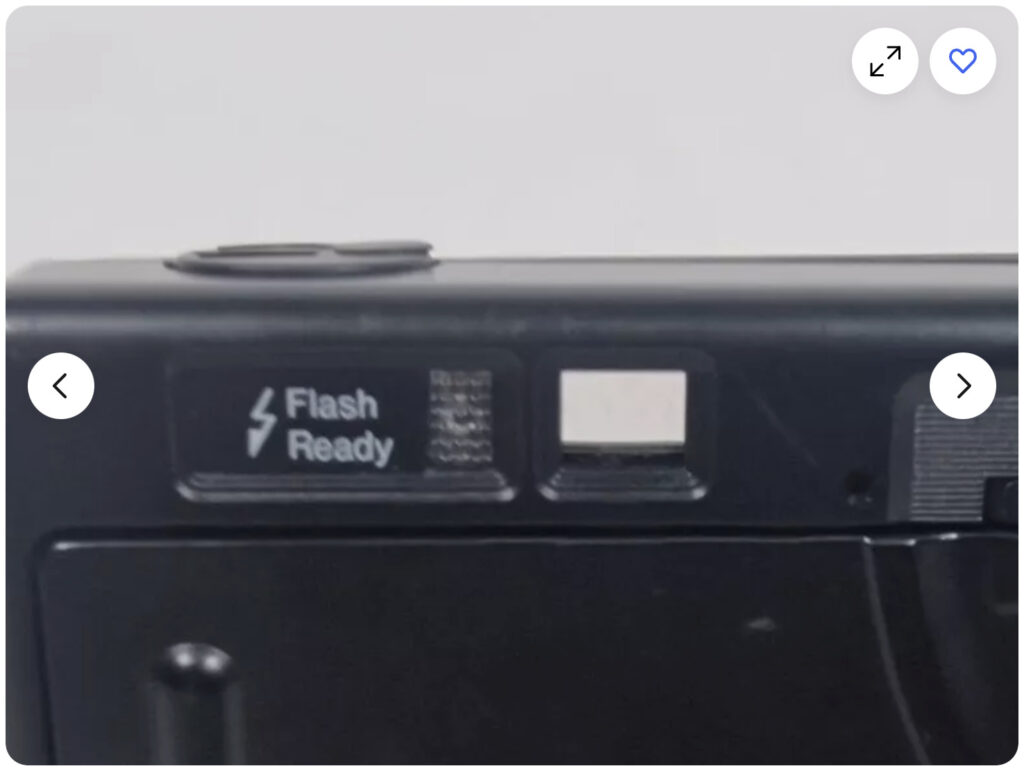

The Halina Vision was the right price (£9.99), looked very familiar and most importantly had the flash that I remembered so well. It’s the weirdest things that stick in your memory and I could vividly recall the whine of the flash charging and a textured, orange “flash ready” light on the back of the camera. Hence, when I saw these photos in an eBay auction I was convinced I’d found the very camera I was looking for.

It turns out this both was and wasn’t the camera I’d been searching for, because it happens to be identical in every way to the Opus Prime. These two cameras are rebadged and rebranded versions of some very generic Chinese camera models that companies would buy in their thousands and pump out as their entry level camera.

So convinced was I that this was the right camera, I began to watch a few potential candidates to buy and nearly did until I realised I couldn’t find one in the colour I had as a child. My original camera was grey and none of the Halina models came in this colour. The design had bought back my memory – the distinctive flash switch and plastic cover across the viewfinder were all so familiar. All I had to do was find the exact same camera in the correct colour.

More digging and searching around the SupaSnaps brand led me to discover that SupaSnaps own or preferred brand were called “Opus.” This was the missing piece of the puzzle and it didn’t take long then to connect the dots and find the correct camera. There, amongst the eBay search results was the exact grey/silver finish that my camera had – just as in the picture above. It turns out they subtly redesigned the same model at least three times, I presume the one I had was a first generation and those which came after offered subtly reshaped grips and bodies. I don’t think the feature set changed!

Strangely, the Opus cameras were selling for much higher prices than their Halina equivalents. In the end, I settled on the blue version as a “close enough” example at a reasonable price – £5 with free postage. It was advertised as “fully working” and this is what turned up…

That’s not exactly a great first impression, is it? Still, in a camera with basically no electronics and next to nothing that can really go wrong, how bad could it be? It might just need a quick clean…

The clean up

Initially, things didn’t look too bad. The choice to use the fluffiest shredded paper imaginable as a packing material wasn’t great when the camera had no protection, not even a plastic bag. It was nothing that couldn’t be cleaned up, despite meaning a complete strip down of the camera – this stuff was everywhere. Then, I popped open the battery cover to be greeted by this:

That is some of the worst battery crust I’ve ever seen and it got much, much worse inside the camera itself. To put it in context, the corrosion had seeped all the way through the camera and appeared in the film chamber at the back. I started a return for the camera and the seller just responded with “keep it.” By now, you should know I can’t just throw something in the bin. Being a simple camera, it should be equally simple to fix so it was worth at least trying to see if something could be bodged back together and cleaned up to a point where it would work even if that meant the flash did not.

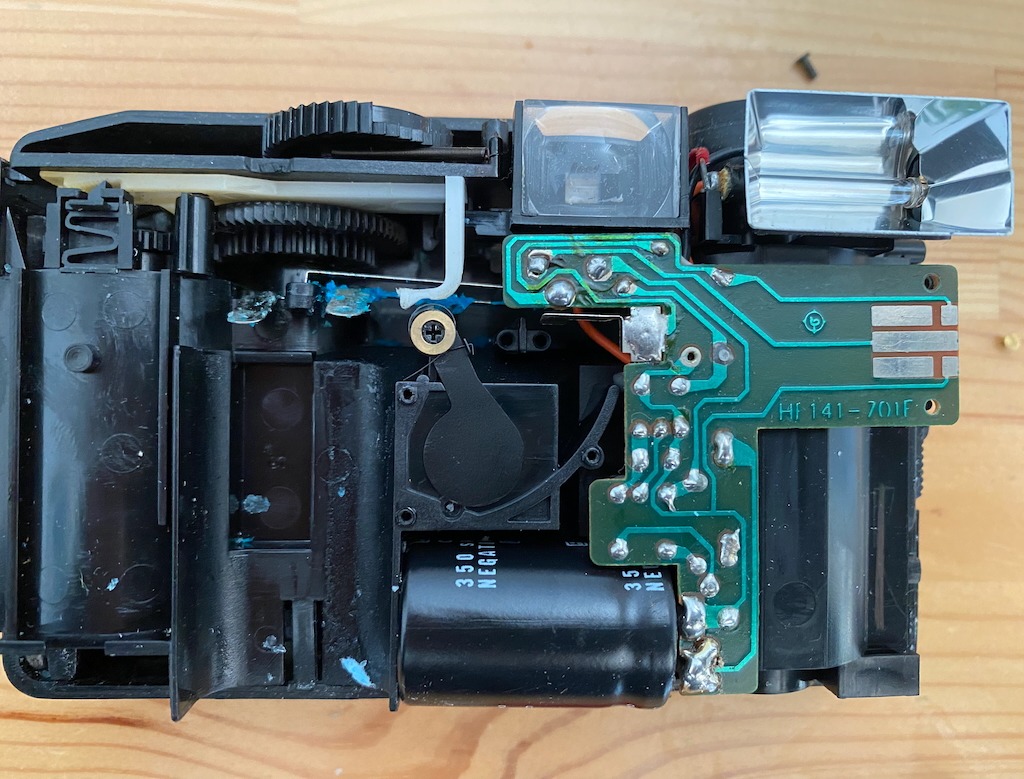

Out came the screwdrivers and within a minute or two the true extent of the battery chaos was revealed. The blue crystals of doom had travelled down the length of one battery contact to the little circuit board which charges the flash capacitor. It had also destroyed the bit where it attached to the camera itself, which is why it appears at an angle in the image above. Without the contact being firmly fixed to the camera body, batteries will simply rattle around inside the holder rather than make a good connection.

I decided to completely take the camera apart and clean each individual element. I also de-soldered the battery terminals so I could bathe them in vinegar and try to polish them back to something resembling normal working condition. As you can see from the picture below, there really isn’t much going on inside these cameras and the shutter mechanism is as old as they come – a simple cover swings back and forth over a fixed aperture, controlled by spring tension.

Miraculously, the battery terminals scrubbed up extremely well and with some fresh solder they reattached to the circuit board without any trouble. I then used the soldering iron to melt what was left of the mounting point around the terminal and hold it firmly in place. This might seem like a bodge, but this “plastic welding” is how they were held in place from the factory, just the tab had broken off from the corrosion. After a total of about half an hour, one vinegar bath and a good scrub with alcohol and other cleaners, the camera was fully working and switching the flash on triggered that memory evoking high pitched whine that I’d heard all those years ago. It was quite the magical experience. It was ready for film.

Then I left it on a shelf for five months…

Settings? What settings?

Which brings us neatly to now and finally having the time and opportunity to take the Opus Prime out for a walk and run a roll of film through it.

I measured the shutter speed at about 1/100th of a second and the aperture looked roughly f8-11 so I stuck a roll of Foma Pan 400 in which can handle outrageous over exposure but would also be sensitive enough for lower light shots. In a camera like this where aperture and shutter speed are both fixed and you obviously cannot change ISO between shots, you really do rely on the incredible latitude of film to record at least something in almost any condition. In that sense, I was not disappointed.

There is a certain beauty to these types of cameras which stems from their sheer simplicity. Because you have a grand total of zero settings to play with there’s nothing else to do but take pictures. Having said that, when you’re used to pretty much any other camera there’s a certain level of uncertainty and distrust when there’s so little feedback during the picture taking process. It’s purely psychological but it feels odd that such a simple mechanism and a hollow plastic clicking noise can result in an image being formed on film.

The viewfinder is typical of a disposable type camera but not as utterly useless as those found on some modern cameras such as the Kodak Printomatic or the hateful nonsense in the Fuji Instax Mini. It does suffer from internal reflections but nothing that stops you from using the camera or framing your image. Accuracy is ok but suffers the closer you get to a subject and talking of distance, there’s no minimum focus distance printed on the camera or lens so that’s guesswork too. I did get quite close to some subjects and I’d say that around 2ft is the closest you can get to something before it becomes blurry.

There are a couple of small but helpful design features built in. The lens cap prevents the shutter from firing unless it is slid to the open position and you cannot take double exposures as the shutter button is disabled until the film winder has been used. There’s also nothing stopping you from doing a mid roll film rewind either. We have now scraped the “features” barrel to its very limit – there’s nothing else happening here!

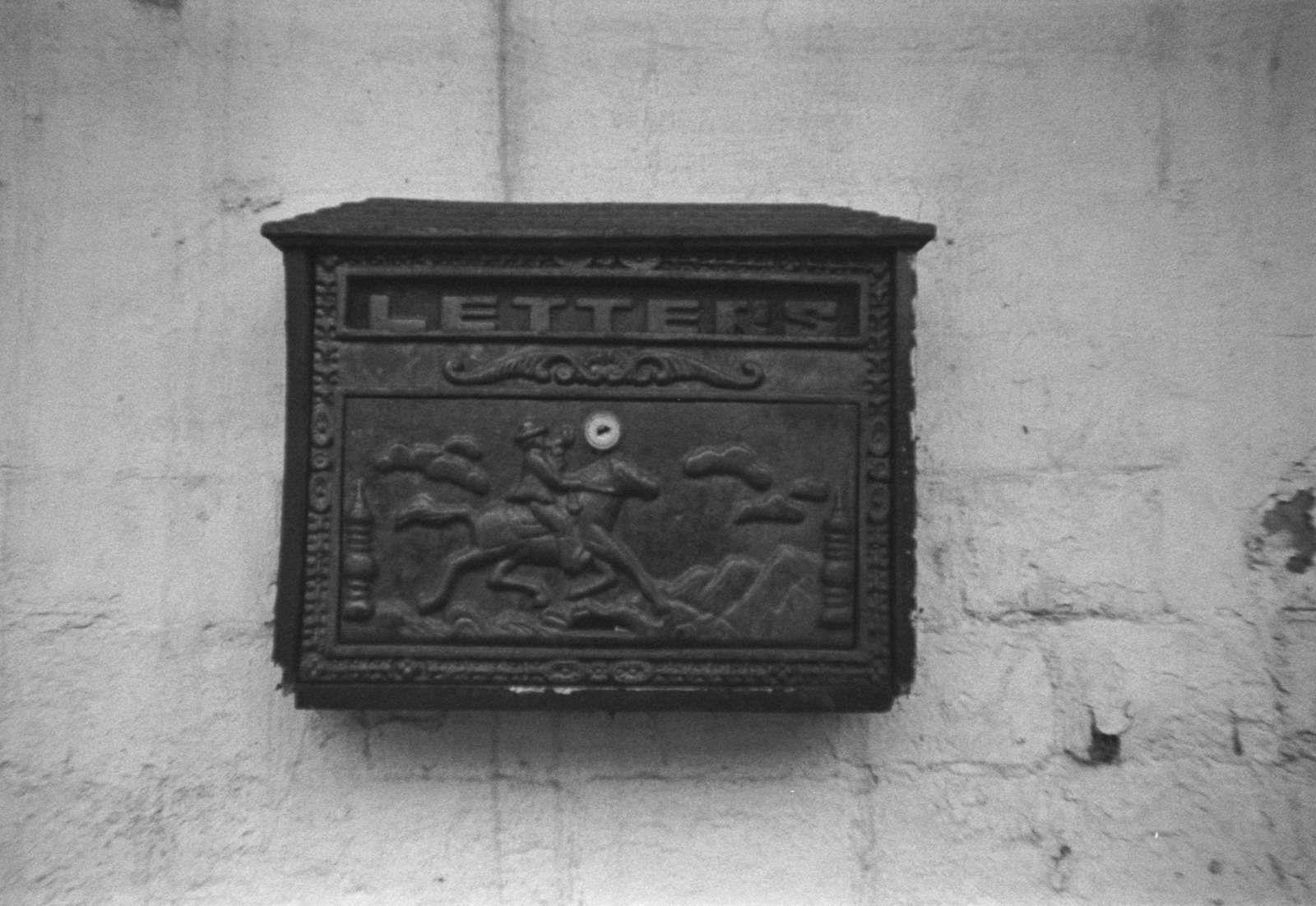

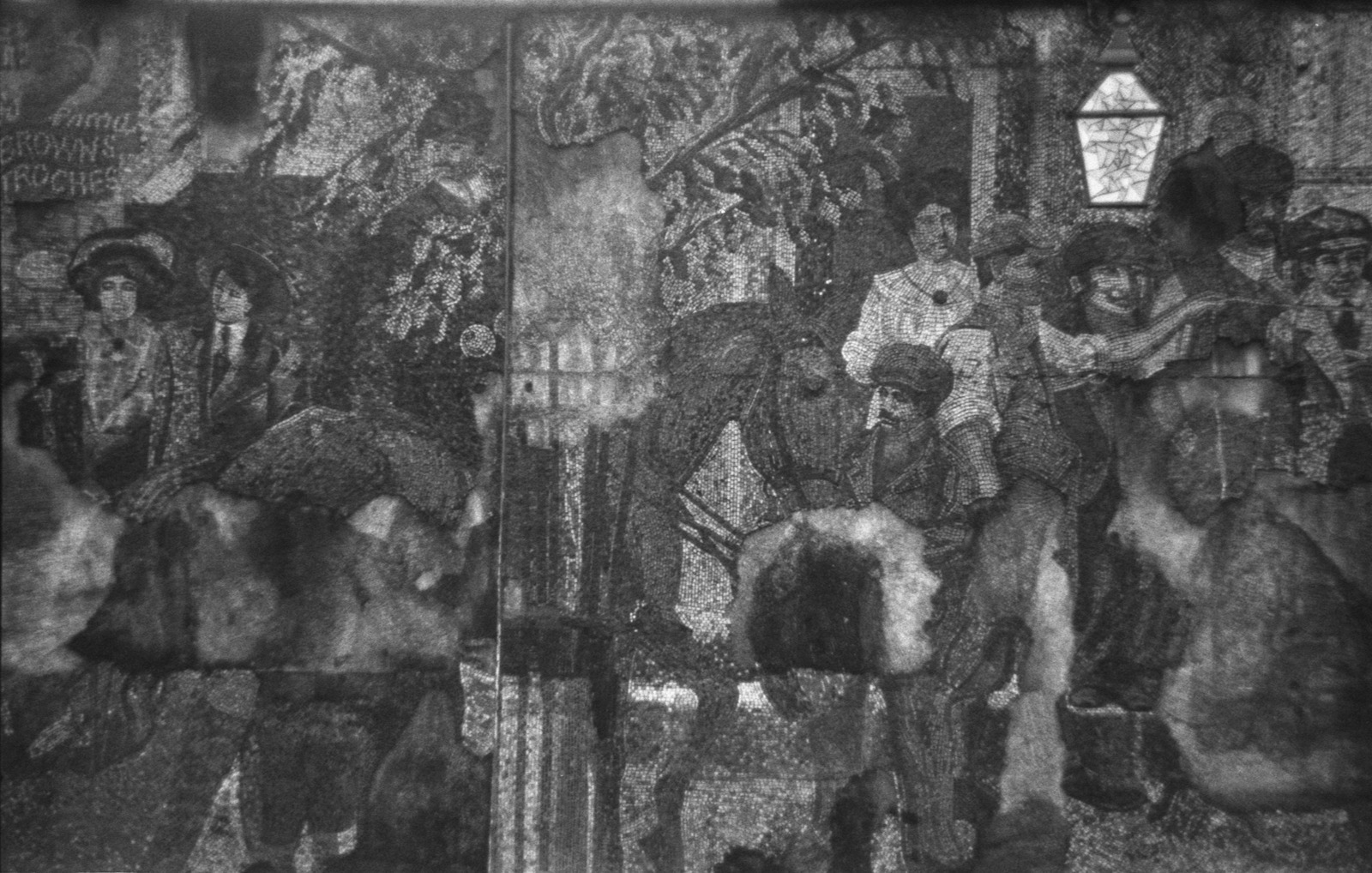

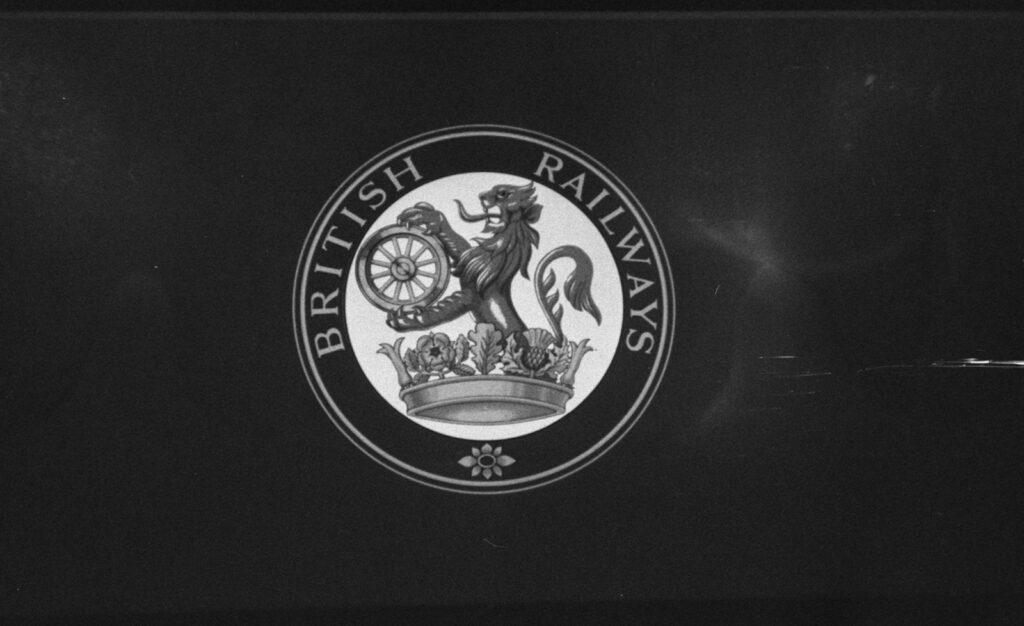

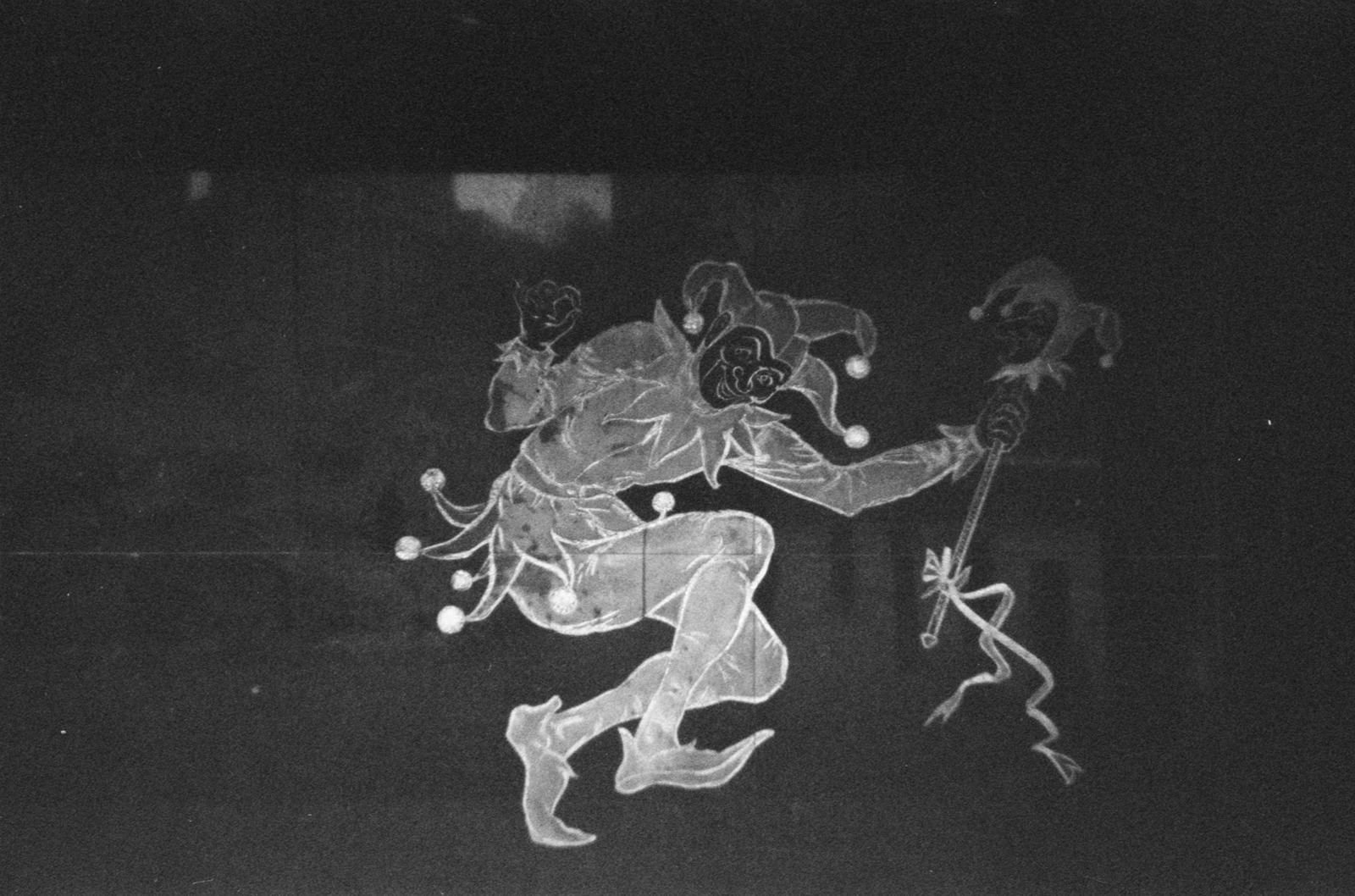

The final images were quite interesting and as I’ve discovered before with similar cameras, the truly remarkable thing is that you get a roll of usable images regardless of the varying conditions the camera was used in. Despite the fixed shutter and aperture, every single image on the roll came out well enough to be scanned and turned into a usable image. This is quite remarkable.

You’d think that all cheap, plastic lens cameras perform at the same level but they really don’t. I’d say the Smena/Cosmic 35 is definitely a step up from this and that was a camera sold at the exact same price point some years before this. However, for a single piece of plastic this lens does produce acceptable sharpness and clarity in the centre of the frame. Outside of this, sharpness is… hilarious. Anything that isn’t in a small radius of the centre of the image is always blurry regardless of scene.

I really enjoyed using this camera again and I tried it out in a couple of different settings to see what came out. I can say confidently that trying to use this camera for street photography was a monumentally bad idea! It just can’t keep up and the softness to the images removes a lot of necessary detail. The only real problem I came across whilst taking pictures was that I repeatedly put my fingers over the lens. On some occasions I’d realise and move before pressing the shutter, but at least 3 or 4 images have my porky digits poking through the right hand side. I’d totally forgotten about this but it did jog memories of getting pictures back from the local lab with a selection of finger close ups… SLR’s really do spoil us.

I went through a roll of film in next to no time, pointing and clicking at anything which remotely took my fancy on a couple of trips out. Winding the film on is effortless with the nice big advance wheel but it is loud and clicky so using it in quiet spaces is quite awkward when you break the silence with your clockwork zipping noises. The same cannot be said for rewinding the film which is genuinely quite painful.

The rewind crank is tiny, inflexible and doesn’t lie flat against the camera when you use it. This makes it hard to keep a grip on the teeny tiny nub that sticks up. On any slightly more expensive camera the part you hold on the rewind crank also rotates in your fingers, this doesn’t as it’s fixed so it rubs agains your skin as it turns. Due to it being slightly too short it is surprising just how much effort is needed to pull the film back into the cartridge and as it tensions up, if you let go then the crank spins merrily round on its own and you then have to wind some tension back into the film to carry on winding. I don’t think this did too much harm, but in the image above I’m fairly certain the areas of white and the lines to the right side were caused during rewind.

I don’t remember any of this from the early 90’s because the few times my camera did have film in back then it would’ve been loaded and unloaded by my dad – I’d have definitely managed to inexplicably mangle it had I been left to my own devices.

Conclusions

Without the personal connection, this is nothing more than a mass produced, cheap as chips plastic fantastic. It’s definitely one up from any disposable camera because it’s not landfill waiting to happen as it can be re-used, but that’s about it. There’s a certain charm to cameras like this and some people get very excited for the “artistic” lens quality. Some just call it crap.

Regardless, I never fail to be amazed by the sheer brilliance of film. What other image making technology is there that can be used in such a shoddy, slapdash manner and yet still comes up with the goods despite being misused so spectacularly? Looking back now, this is probably what made these cameras so ideal for children. Yes, the 8 year old me would’ve loved buttons to press, an exciting LCD display to look at and a zoom lens, but realistically I’d have had no idea how to use them and would still have just stuck my finger half over the lens by accident.

As first cameras go, this wasn’t a bad choice at all and I do remember being happy enough with the prints that came back from the few films that went through it. I cannot for the life of me think what happened to those images, though, they’re almost certainly long since lost, probably thrown away at some point which is not great but I doubt they were of anything spectacular! The last time I used the camera was in 1998 to take pictures of the local area for my GCSE Business coursework where we had to suggest an idea for a business and then include photographs of likely locations where we’d put our chosen company. What happened to it after that is anyone’s guess.

Arguably, there is no equivalent today. If you wanted a child to have a stand alone camera the choices are either limited or expensive and a lot of the time the options, settings and features of a digital camera just get in the way of doing what a child wants – press button, get picture. There are toy digital cameras but their image quality isn’t even up to the standard of this Opus camera from over thirty years ago. I suppose then that the best option for children these days has to be the instant print type cameras like the Canon Ivy Cliq / Zoe Mini, Kodak Printomatic or similar.

It is incredible, however, that all these cameras, old and modern, all have one thing in common – their image quality is terrible and that’s fairly unforgivable of the modern cameras when you consider even a £50 smartphone will produce much better pictures. These cameras, completely free of electronics, have one thing on their side and that is no matter how bad the lens is, film will always give you something and probably at a higher resolution and quality than a poor thermal print from a modern digital camera.

I’d love to conclude by saying this is the camera which sparked my love of photography. You see so many interviews that go along the lines of “my dad gave me a camera when I was 6 and it switched a light on in me….” This didn’t happen to me. It was just a camera, it was certainly fun to be able to take my own pictures but it didn’t ignite a fire in me – that came much, much later when I bought an Ixus 500, but nevertheless it will always be the true first of the firsts!