Getting to the point where I can review a T80 has been a long, long road. Whilst the T90 has a reputation for sticky shutters and dead LCD panels, the T80 seems to be an absolute magnet for exploded, leaking batteries and other indecipherable electrical faults. It has taken me well over a year to lay my hands on one that I can put a roll of film through. This includes the rather embarrassing realisation that due to a total oversight on my behalf when trying to repair one body, I had actually repaired a T80 over six months ago and just not realised it.

Due to the obscurity of the auto focus AC lens systems, these cameras inevitably now command the “rare” eBay price premium and certainly not because they are particularly brilliant, but because they are so fragile they really are quite few and far between these days.

Why, then, did I go to all the hassle of pursuing a working copy? Simple, really, it’s a curiosity and I can’t help myself. First attempts in technology are always interesting and a fantastic way to remind yourself about what its like to be an early adopter of something new and innovative. How good was Canon’s first attempt at auto focus and what impact did the T80 have on the future of camera design? Let’s find out.

In this review:

- It’s 1985, can we have chips with that?

- The “picture selector system”

- A new range of AC lenses

- Using the T80

- Winder Woes

- Conclusions and learning

It’s 1985, can we have chips with that?

There’s no need to go over old ground too much, we’ve spoken in depth about the Canon T series in the T90 review and also my previous tales of T80 repair woe. To summarise, the 1980’s was the decade of the microchip. Cheap, affordable electronics in tiny packages found their way into most consumer devices whether they needed an injection of binary or not.

All camera manufacturers were struggling to encourage customers to buy in to SLR systems due to the rise of affordable, capable compact cameras that fulfilled the needs of most consumers. In an effort to tempt people over, Canon redesigned their whole range of FD mount cameras to be sleek, black plastic marvels with what was described at the time as “space age” styling. They made heavy use of plastics throughout the range, adorned with rather nice signature gold lettering. The goal of the entire T series range was simple – automate everything.

Consequently, the T50 was effectively a point and shoot SLR, it had program mode and that was your lot. The T70 gave back some of the control that serious amateurs wanted whilst the T90 was a beautiful piece of engineering for professional use which quite literally changed the face of photography forever. One thing was missing in this tidal wave of automation, however, and it was a big one – auto focus.

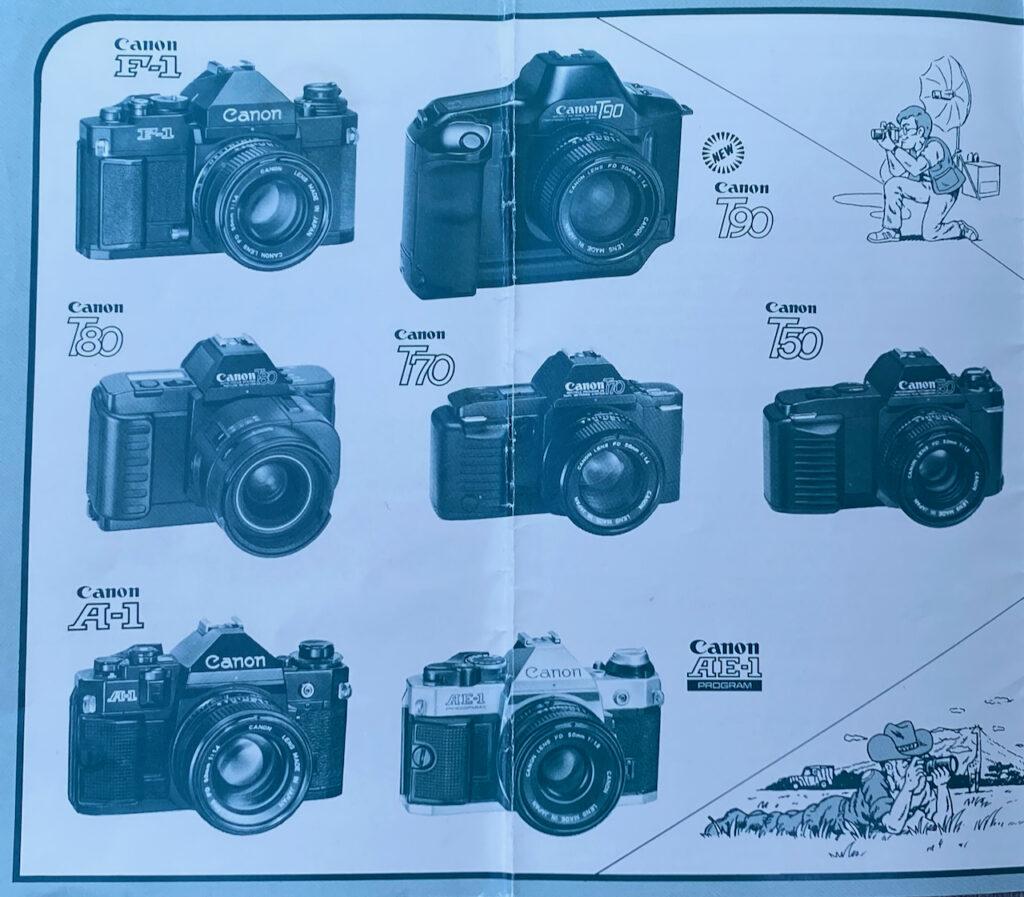

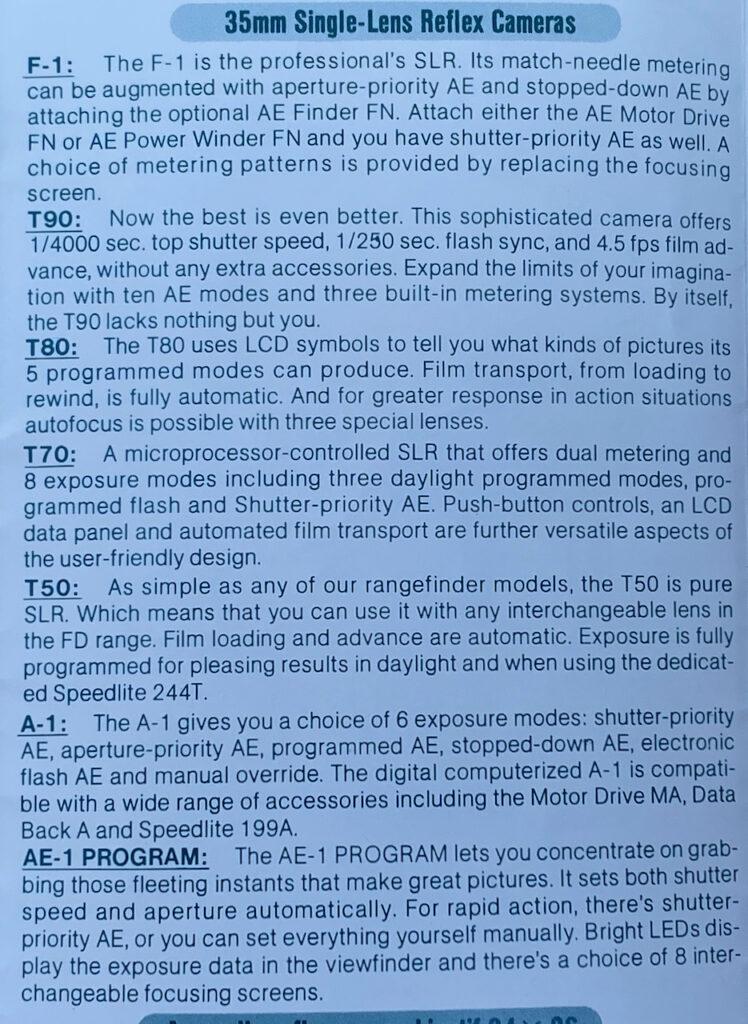

Looking at the 1985 lineup of cameras, Canon were still pushing the A1, AE1 and now seriously aged F-1. At this point in time, none of those models made sense. Whether you loved or hated the T series, the T70 offered everything the A1 and AE1 did, but in a package with better ergonomics, improved metering and a few more convenience features such as using standard AA batteries. Admittedly, these days I’d still choose an AE-1 over any T series save the T90, but that’s with the benefit of retrospect and an irrational love of that camera.

The F-1 could possibly have had an edge in that it was arguably more robust than a T90 and could shoot in a fully mechanical manner, but the T90 was in every other way a more capable imaging tool with superior ergonomics, metering, motor drive and more. How odd, then, that in the 1985 leaflet above, Canon describe the F-1 as “the professionals SLR” and then bizarrely the T90 as “the best got better” whatever that means?

Who knows. As I’ve said before, this was definitely a time of throwing as much at the wall as possible in an effort to see what stuck. Of course, it may also have been a time when there was just a lot of 1970’s stock that needed to be sold off!

The “picture selector system”

I’ve seen a lot of retrospective reviews of the T80 and a fair few can be summarised as follows:

The T80 looks nice, very 80’s retro. The AC system was a nice idea but is actually garbage. Where’s my manual control? Don’t bother, buy an EOS camera or stick to A series FD.

Everyone, ever.

There are, or course, a variety of viewpoints about this camera and one notable exception was Mike Eckman who clearly loves his T80 and wrote a very fair, balanced review of it which includes some great magazine articles from 1985 when the T80 was first released. However, the point here is that a lot of the time people are entirely missing the point in this camera.

The T80 was never designed nor marketed as a professional imaging tool, quite the opposite. This camera was intended to be the ultimate point and shoot SLR on steroids. The brief for Canon’s design team looked something like this – take everything customers love about their compacts, add in the benefits of interchangeable lenses, a proper shutter and through the lens viewfinders, remove all of the complexity and automate what’s left. Do all of that and you have the T80.

Those of you into computing will be familiar with the term “abstraction.” Abstraction describes the process of taking something which is intrinsically quite complex and intricate, hiding all of that complexity away and presenting the user with the most simplified possible interface. The goal being the user doesn’t stop once to think about how something works, they just do it. A good tool should feel like an extension of your body, not a puzzle to be solved.

Looking back now, we are in a golden age of abstraction. The computer systems we use, such as our phones, are extraordinarily complex things, yet they can be operated by a two year old. This hasn’t always been the case, companies like Microsoft spent tens of millions of dollars researching how to make computers more accessible for Windows 95. That investment paid off and changed the face of computing and operating systems forever.

The world would wait another 12 years before we got even close to another revolution in operating system and user interface design when in 2007, Steve Jobs and friends came along and utterly blew the world apart with the multitouch iOS operating system that suddenly unlocked computing for people who never before would’ve dreamed of owning a PC. How quickly we forget that it was only 16 years ago when we lived in a world where your gran was not going to be sending you a quick message with a picture attached because the difficulty barrier was simply too high.

Back in 1985, user interface design was positively embryonic and there were very few previous metaphors and examples to use as a starting point for whatever you were making. Canon, then, faced a challenge in trying to come up with a system that could abstract away the intricacies and complexities of the various styles of SLR shooting that people might want to undertake. Keep in mind that this was a time when you couldn’t just whack a nice colour touch panel on a device and make a pretty menu. At best, you’d get an 8 bit CPU, a tiny amount of memory and a liquid crystal display like your average Casio watch had. That’s it.

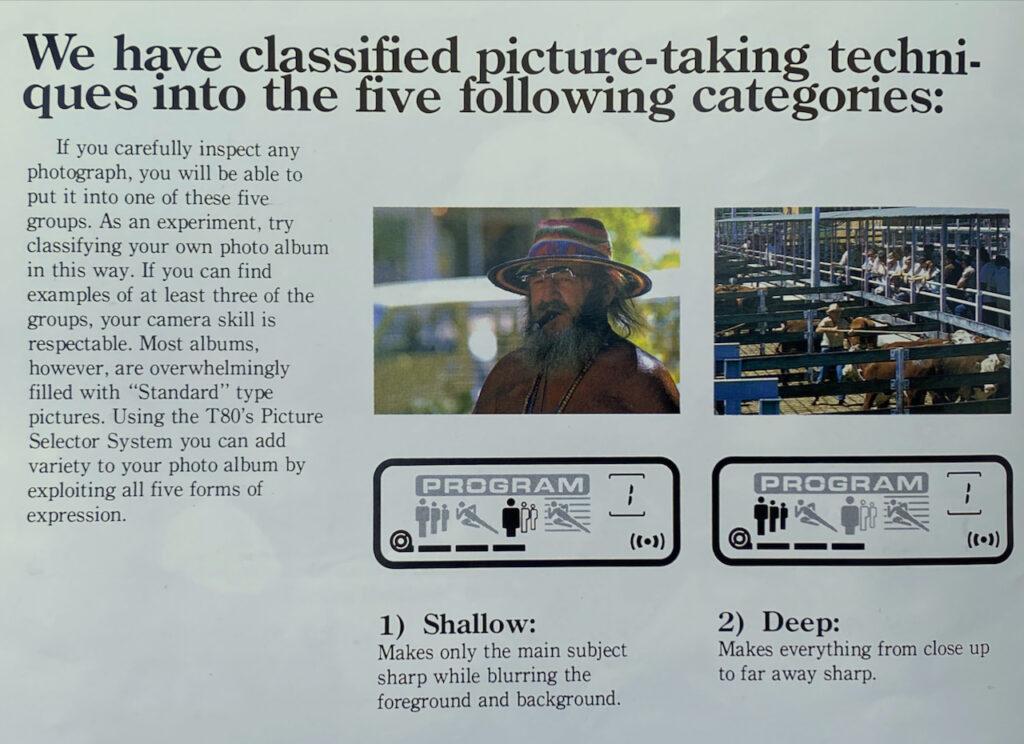

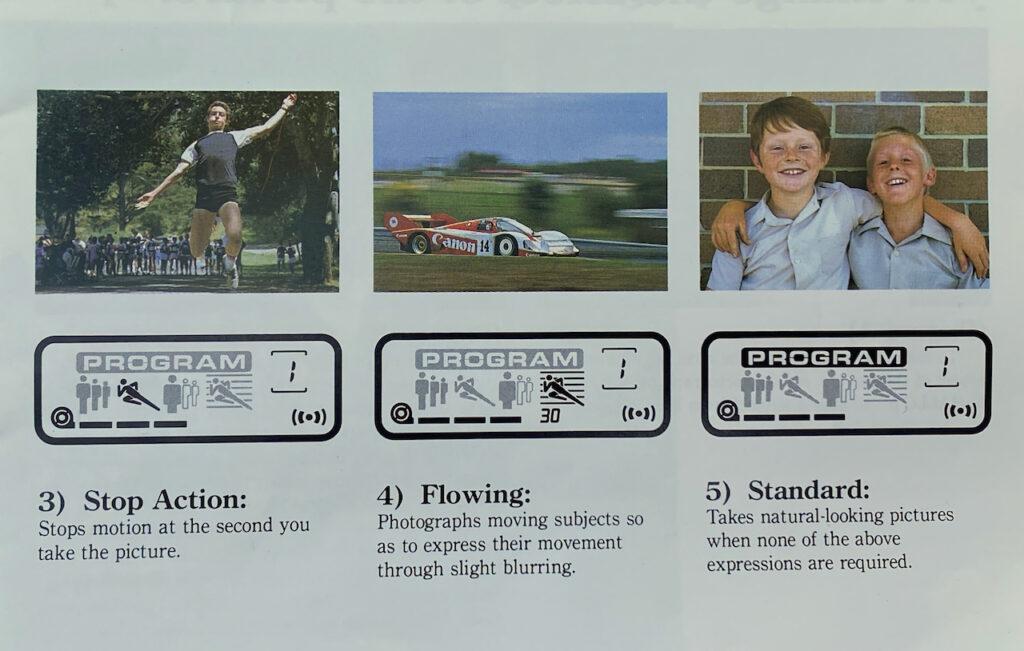

Canon went away, did their homework and concluded that there were only really four different ways in which you’d want to take a photograph – five if you included snapshots or “general” scenes. Having abstracted photography down to just five styles, they then created their pictogram “picture selection system.” The premise was simple; decide what type of image you’d like to create, flick the selector until that picture type was highlighted and the camera would take care of the rest.

The idea isn’t a bad one and goes a long way to achieving the goal of simplifying SLR photography techniques such as controlling the depth of field or blurring a background whilst panning. This was R&D money well spent as these assisted shooting modes all came back in later EOS film SLR’s and many consumer DSLR’s all featured these pictograph modes on their dials along side the traditional “creative modes.”

The T series of cameras is often overlooked for the long term effect they had on the future of Canon’s camera design philosophy and feature set. Although the T90 undoubtedly set the tone for all future SLR’s, the T80 introduced assisted shooting and AF, whilst the T70 became something of a template for the mid range, enthusiast level camera. The T50… well, at least it looked nice

To educate new users about how each of the new modes worked, the T80 came with a user manual and also a booklet called “Image Hunting” which was “essential to read.” It showed a series of carefully curated and set up images to give people ideas about what the possibilities were with their new camera. The choice of some of the subjects is questionable at best – the gentleman they chose for the “shallow” mode picture is a most terrifying clone of the mysogynist horse racing loonatic John McCririck. Canon could afford any model they wanted, and someone looked at that picture and went “yep, that’s it boys, more facial hair than Gandalf and a manly pipe – that’s the look for our new camera.”

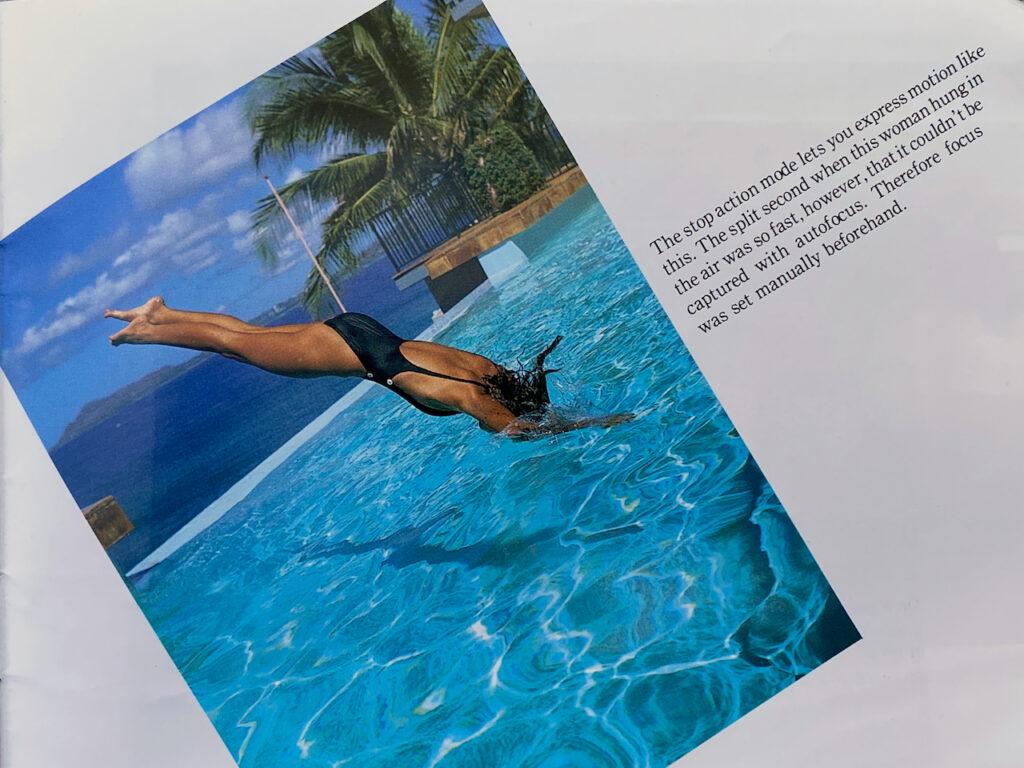

Other examples include this really rather good picture of a woman diving into a swimming pool somewhere exotic. They definitely took it using an AC lens as well, because the motion was “so fast, however, that it couldn’t be captured with autofocus.” Too right you couldn’t, the fact that the AC lens comes with a “servo” mode must surely be one of Canon’s greatest jokes in their long history. I’d love to see anyone successfully track a subject with one.

Finally, we have the “cute little girl” who now is something of a “middle aged woman.” The girl in this picture has to be at least 45 now. Come to think of it, our diving lady above will be well into her 60’s by now. Jesus.

A new range of AC lenses

On to the star of the show, the thing that makes the T80 more than just a camera with some creative shooting modes – the auto focus.

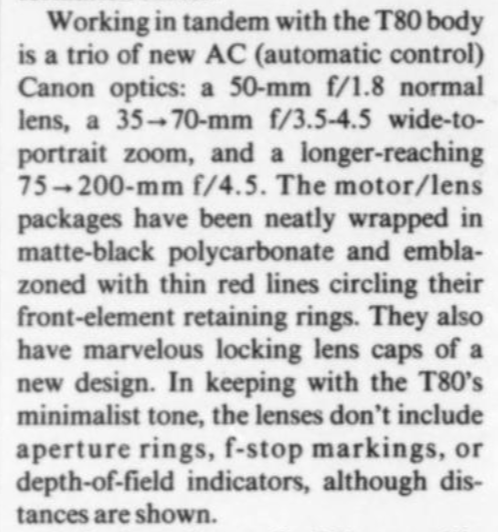

Canon took three FD lenses which covered pretty much all of the most common focal lengths and bolted a rather bulbous focus motor to the side and called them “AC” which apparently stands for “automatic control” according to Popular Photography Magazine and we should take this as fact because I can’t find any other explanation for the abbreviation anywhere else!

Auto focus is achieved through communication with the camera, the lens itself merely responds to signals sent through connecting pins on the mount which tell the lens to wind the motor forwards or backwards.

Inside the T80 is a very first generation AF system which looks for horizontal lines in the image that has been diverted underneath the mirror assembly and moves forwards and backwards until the image is in focus. This is as first generation as it gets. There are no quick Ultra Silent Motors (USM) here, nor multi point AF, selectable focus points or anything you’re used to. Focus is centre point only and yes, you really can manual focus a lens in half the time this system takes. What is cool is that the auto focus system is still engaged when you use a manual focus FD lens – you get a nice friendly beep which confirms when you’ve focussed correctly and it is always accurate. It’s quite nice to have that confirmation even though you don’t really need it.

But! To look at it like this is to miss the point somewhat. Yes, auto focus did rapidly get much better after this attempt, but the premise and technology it was built on ended up being the solution that Canon used successfully for decades after. Nikon went down the “all in camera” route and everyone thought they’d got it right until Canon stuck to their guns, perfected making tiny focus motors inside their EF lenses for the upcoming EOS system and then promptly engaged the ultimate smug mode.

Handling wise, the extra bulk of the focussing motor makes absolutely no difference but there are some dodgy design choices which have been made in the name of making them look sleek and beautiful.

You can manual focus, but the focus ring is, at a rough estimate, 80% obscured by the lens housing making it only accessible in two small gaps either side. The housing also plays havoc with filters – the 50mm lens will accept a filter no problem but put the exact same filter on the 35-70mm lens and it will no longer focus as the filter slightly fouls the inner plastic housing. Talking of the 35-70, the zoom lever is a reasonable attempt but takes a lot of getting used to where it is if you want to change zoom without looking for the lever first.

There’s nothing wrong with the image quality that either lens produces. the 35-70 has a slightly better close focus distance which they promoted as being the “closest focussing zoom lens available” at the time. Whether that is true or not, I have no idea but macro it is not. Overall, I quite like the look of the AC lenses, they definitely had that futuristic vibe about them and a lot of effort went into making them look as sleek as possible. Also, check out the red ring! I’m totally taking that as owning another two L lenses…

Canon T80, AC 50mm F1.8

Canon T80, FD 50mm F1.4

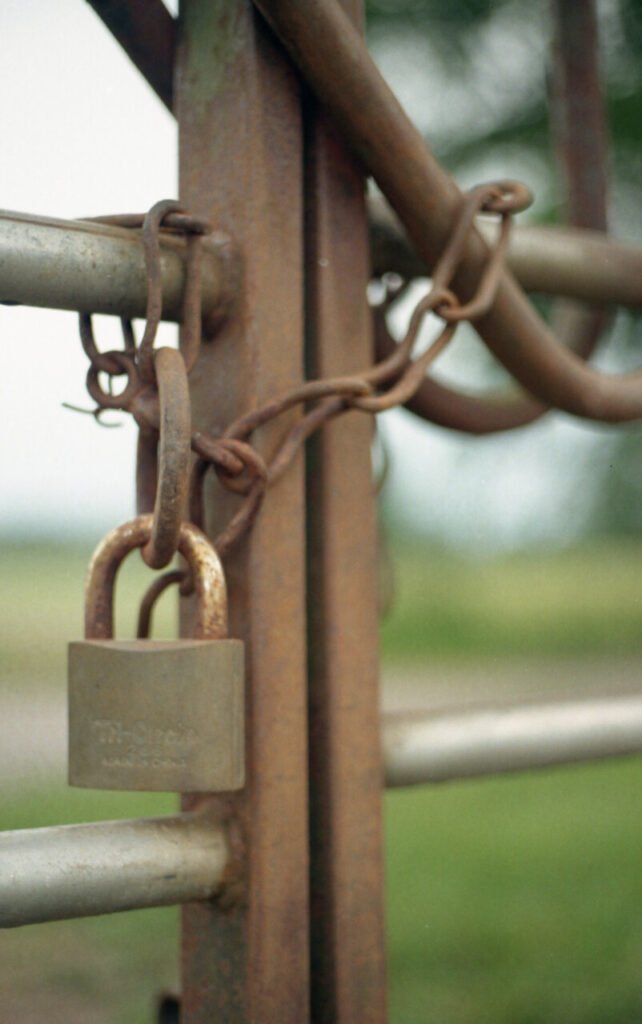

I tried to do a “fair” side by side comparison of the AC 50mm and a standard FD manual focus 50mm. I put the T80 in to “shallow” mode and focussed on the padlock. There are no other settings you can change on the camera so any differences are then down to whatever metering, F stop and shutter speed decision it made. Looking at the pictures I’d say that neither lens is wide open, but still fairly wide, something around F2.2 seems to fit the depth of field here. I’m guessing that Canon would’ve programmed the shallow mode to err on the side of caution, if it went with F1.8 then there’s the risk that with the smallest of movements you’re going to be out of focus everywhere.

Talking of focus, you can see the issue with the slow nature of the AC lenses in these pictures. The wind was blowing reasonably strongly and it took quite a lot of patience to get the shot off when the gates weren’t moving. The AC lens constantly hunted back and forth when trying to hold focus on the padlock. Between clicking the shutter and the last focus motor movement, you can see that the frame is very slightly front focussed. The FD 50mm, on the other hand, was much easier to focus and also to make tiny adjustments by hand to compensate for any movement. In terms of image quality, you’ll see throughout this review that the FD lens gave a much more pleasing image overall than the AC lenses.

Using the T80

Let’s get straight to the point. It isn’t the lack of control that gets to me when I use the T80, it’s the lack of information. I get that they went all out to simplify things, but would there have really been any harm in just letting us know which shutter speed the camera had chosen? I’m not even asking for the F stop, after all you cannot change it manually on an AC lens, but just give me something!

In fairness, the T80 really does do a good job of selecting sensible settings for each shot and does invariably get it right. Whenever I start to criticise the T80 I have to pause for a second and remember that I’m not who this camera was designed for, I’m not the user they had in mind and I wouldn’t buy this camera for that reason! So, if we put it in context, is it really that bad that there’s a lack of information… Actually? No.

When you just accept that the T80 is meant to do everything for you, life gets easier. It’s a great camera, then?

Well…

No.

There’s just no hiding from the auto focus performance. It’s especially bad when you do actually put it in the context of the user this camera was designed for. Every so often you’ll point the camera at a scene and it will quite magically and (for an AC lens) quickly grab focus, but this is absolutely the exception rather than the norm. In nearly all other situations the T80 noisily hunts back and forth, back and forth, back and forth until you give up and then fumble around with your fingers trying to find the tiny opening for the focus ring.

I can’t help but think that those who bought and used this in 1985 must’ve felt slightly duped. SLR’s were meant to be the flagship cameras, much more powerful and flexible than their compact counterparts. Having lashed out your £300 or so, you’d have been fairly bewildered as it mindlessly just shunted the lens in and out against the focus stops.

No matter how good the pictograph system is, and it really is a nice idea for new users, the immersion in the whole creative process is rather ruined by the jarring awfulness of the pitiful attempt at auto focus. Canon knew this, they did their testing and found out all of the weaknesses before deciding to release the camera anyway. It is clear why only 3 lenses were ever produced and then quickly abandoned in favour of the EF system to come.

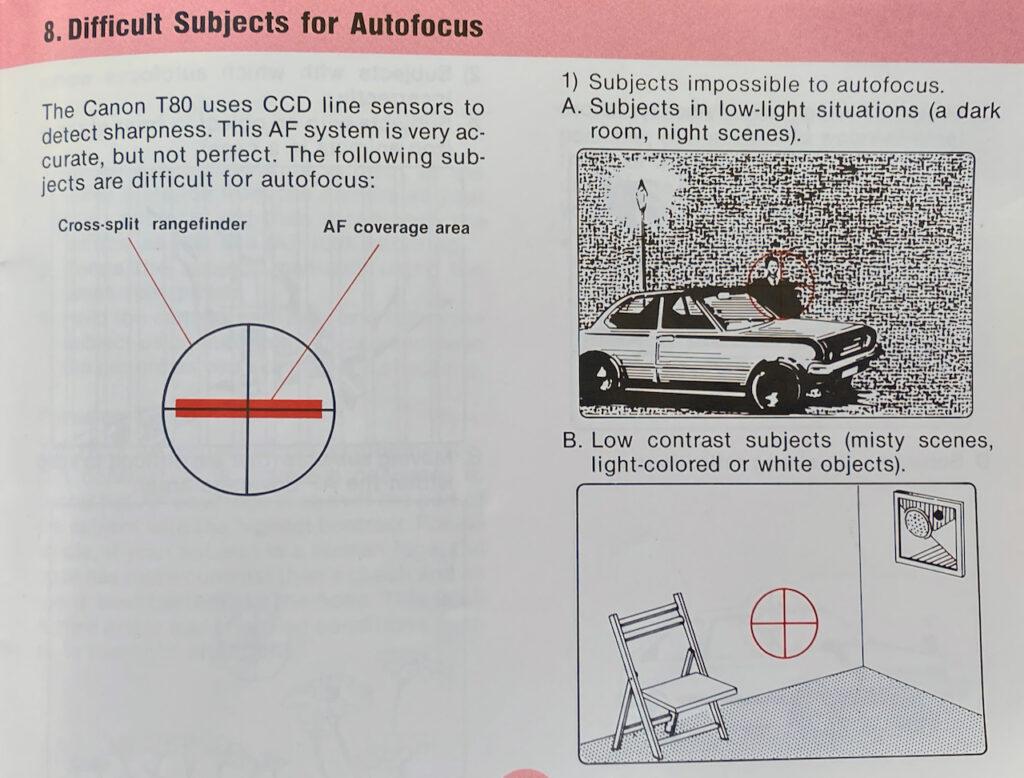

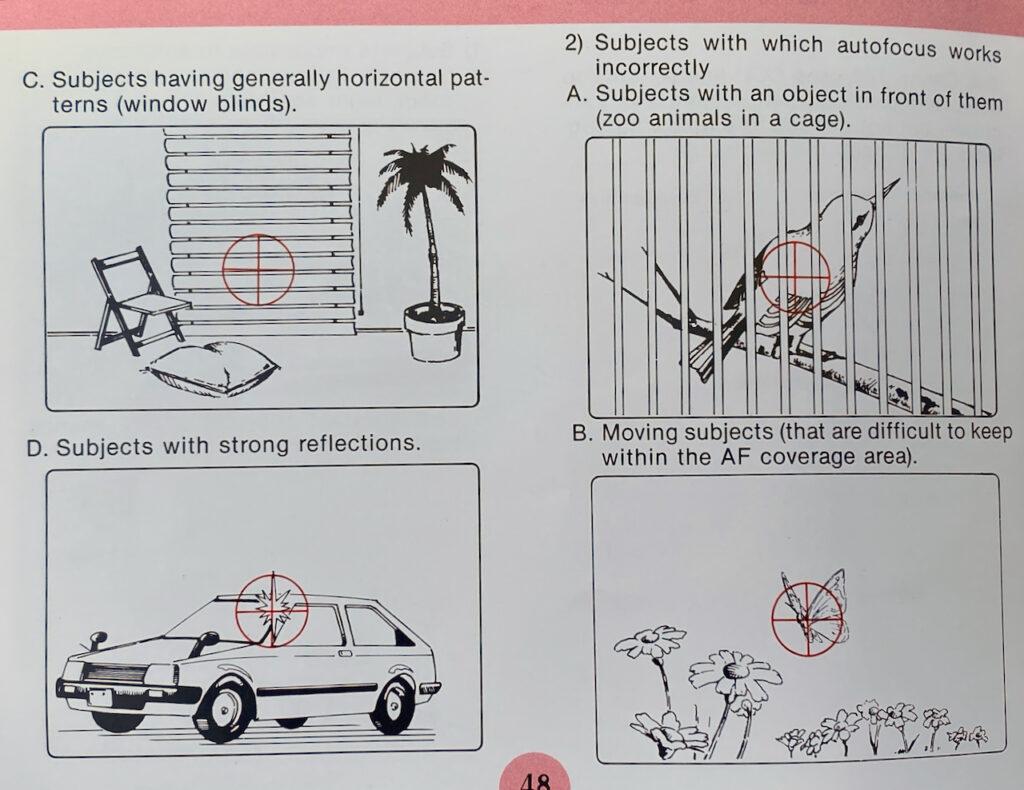

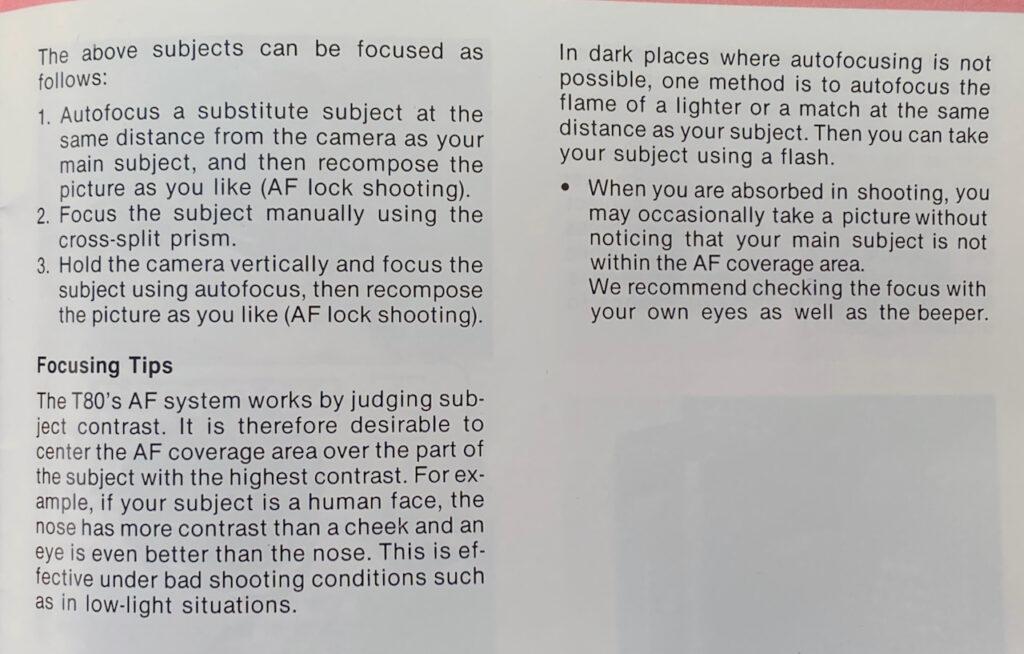

The manual has a wonderful section where it explains just how many things the auto focus system is confused by. Slightly dark? Nope. Wrong type of lines? Nope. Reflections? Do it yourself! Moving subjects? Don’t be silly! Indeed, unless you have a nice, contrasty scene with vertical lines in it then you may as well just go home.

Canon FD manual focus lenses are an absolute joy to use on the whole. Their construction is reassuringly solid, the focus rings are massive and easy to find, their action smooth with just enough weight that you don’t swing straight past your focus point. With very little practise you can become very adept at quickly spinning the lens into focus and firing off a shot. It’s all very natural. The AC system was a nice try but absolutely no better than just sticking with what you already had, making the T80… well… pointless.

Once you’ve flicked through the various modes, appreciated the automatic loading and winding, tried the AF and then given up, there really isn’t anything left to try or talk about with the T80. It’s all rather sad really, because so much of this camera design went on to be really very successful. Canon soon realised that cross type sensors were the way forward and perfected this system within a few years of the T80’s launch. The pictograph system ended up on every single consumer oriented camera in their lineup for decades to come and their bet on automation was completely right.

Winder Woes

I ran my last roll of Kodak colour film through the T80 and it became gradually clearer that all was not well with the bodge-o-matic machine that I’d nursed back into life. The automatic film wind began to sound worse with each shot and seemed to be very laboured between each frame. It was very telling to fire the T80 alongside a T70 – the frame advance on the T70 was at least twice as quick. I’m fairly sure this wasn’t the case when both of these cameras were new out of the box.

The roll came to an end at frame 28 on the T80’s counter, with a click and a whine the automatic film advance had ground to a halt. I didn’t want to damage the roll or lose any shots by investigating whether the roll had truly run out or not, so decided to rewind it. Well, I tried to rewind it at least. This is the point where the T80 breathed its last and decided to make endless rewind motor noises without actually taking the film back in. It did this even when the batteries were removed and put back in again and now all this particular body does is attempt to not rewind. Forever.

I took it home and, using the trusty dark bag, opened the back and manually rewound the film before paying the eye watering £14 it costs to develop a roll of C41 film these days. £14! Luckily, the roll came out unscathed and the developed pictures really did look rather good, it’s just a shame that I lost 8 frames from the roll because of the dead winder.

Conclusions and learning

I can’t help but think that the conclusion to this review is going to be somewhat predictable, but we’ll go there anyway.

Let’s start with the positive, the metering really is excellent – absolutely spot on in nearly all types of scenes and situations. I guess really it had to be considering you have no control over it, but it really is superb for the time this camera was released.

I began this review by suggesting that other users of the T80 had perhaps missed the point in what this camera was meant to be. I stand by that point – it was never meant to be an SLR in the way we think of nearly every other camera of this type, this was an early attempt at fully automatic, point and shoot photography. Why then am I also so negative about the T80? Have I forgotten my own point?

No. The bottom line is the T80 just doesn’t work, both conceptually as a point and shoot and (these days) physically. The pain of going through eBay, trying to pay sensible prices and repairing what is apparently a very fragile camera wasn’t really worth it in the end. I always enjoy the repair process, you will always learn something even when it goes wrong and boy did I learn not to be an idiot this time round! However, as far as I can tell from looking for used bodies and then my own dying on me 3/4 of the way through a film, I cannot recommend that anyone goes after one of these unless you happen to have too much money and no idea what to do with it next. My experience is that most T80’s are broken and the one’s that aren’t are about to be.

The whole point in the T80 is to experience Canon’s first effort at a fully automated, auto focus camera system. Nostalgia is one thing but it only goes so far. The AC system really gets in the way of actually enjoying photography and this is the key to my problem with it – it fundamentally doesn’t do what it set out to, which is to get out of the way and just allow you to shoot film. With the AC lenses attached, it’s a really frustrating camera to use. The silly thing is that when you attach an FD lens it becomes “just another camera” that’s reasonably nice to use but then you’re left with a fully automated body that gives you absolutely zero feedback about what it is doing.

If you only used a T80, I guess you might not notice this lack of information or you’d gradually get used to it. When it died, I whipped out a T70, put a roll of Foma 100 in and started shooting. Instantly I was struck by just how much nicer the T70 was with its clear, bright viewfinder information. Even though I used the T70 in program mode, it pops up the F stop its thinking of using and this is just so useful, you know exactly how much depth of field you’re getting and also intuitively know whether you’re about to start risking low shutter speeds. There is no fathomable reason why Canon omitted this from the T80. Yes, I get they wanted to just completely simplify and abstract the whole experience, but its too much – novice users could’ve quite happily ignored these little numbers if they so wished.

At the time, the T80 was an admirable concept with great intentions. We shouldn’t forget that some of the innovations on this camera set the tone for all future models to come and so, in that sense, it isn’t a failure. However, even at the time the AF was no great shakes and as a retrospective experience its awful. For the modern film user, there is no compelling or decent reason to use this camera. The FD system is wonderful and there are countless cameras that will do those lenses justice. If you want to experience the T series, then there’s the beautiful T90 for those with deep pockets and the very reasonable T70 which will tell you all you need to know about being a mid 80’s Canon user.

Trust me, I understand the lure of buying old gear, finding reasons why I really need to try out an old camera for a review or simply just to know what it was like, but believe me, save yourself the hassle – the T80 is not that camera.

Share this post: