Forty years is an unimaginably long time in the world of electronics and computing. The early 1980’s saw the birth of a brand new, ground breaking era of personal technology that was going to revolutionise our lives – “home micro computers.” The only problem was that back in 1983, no one really knew what we were meant to do with a computer at home nor why anyone really needed one.

This isn’t an exaggeration. Magazines from the era were filled with adverts for incredible utilities like recipe managers (because who doesn’t crack out the Commodore 64 to bake a cake?), home “accounting” software, primitive forms of databases and grand descriptions of games that were little more than a poorly written story book with limited interaction.

When you’d catalogued the contents of your Betamax collection, transferred your latest transactions by hand into a program that would then calculate your remaining bank balance ten times slower than just doing it by hand, people rightly shrugged and asked “is that it?” before promptly erasing the cassette tape to use for something more useful like recording The Archers off Radio 4.

The 1980’s saw manufacturers trying to shove these new miracle chips into any and every device possible, the word “digital” became a marketing term and futuristic black plastic with go faster lines painted on was all the rage in consumer electronics and the camera market was not going to be left behind. Hence, the Canon T series was born.

The T series, and indeed most cameras of the time, are so hard to understand in retrospect. Whilst the technology of the day was certainly impressive in context, it still wasn’t quite where it needed to be and so this whole series of cameras went from a total manual/automatic mash up in the T50, to a failed autofocus experiment with the T80 to the dual processor, futuristic T90 we’re here to talk about today. Indeed, looking back now, the entire line-up looks like a series of market experiments.

Before buying one and doing my homework, I had the preconception that the T90 ultimately was a missed opportunity. That really is too much of a simplistic conclusion though, and we must apply some period correct context and understanding to give the T90 a fair shot. In 1986, during a period of intense, relentless technological development, the T90 was actually groundbreaking in many ways, technically brilliant and for about 12 months, one of the most competent imaging tools the world had ever seen. What’s more, it can be argued that this single camera saved Canons photography business and launched them to stratospheric highs for decades to come. Let’s find out why.

In this review:

- An awkward decade

- T is for Technology, and lots of it

- A change of design language

- Pro body, no AF?

- Common failures

- Driving a tank – Using the T90

- Conclusion and legacy

An awkward decade

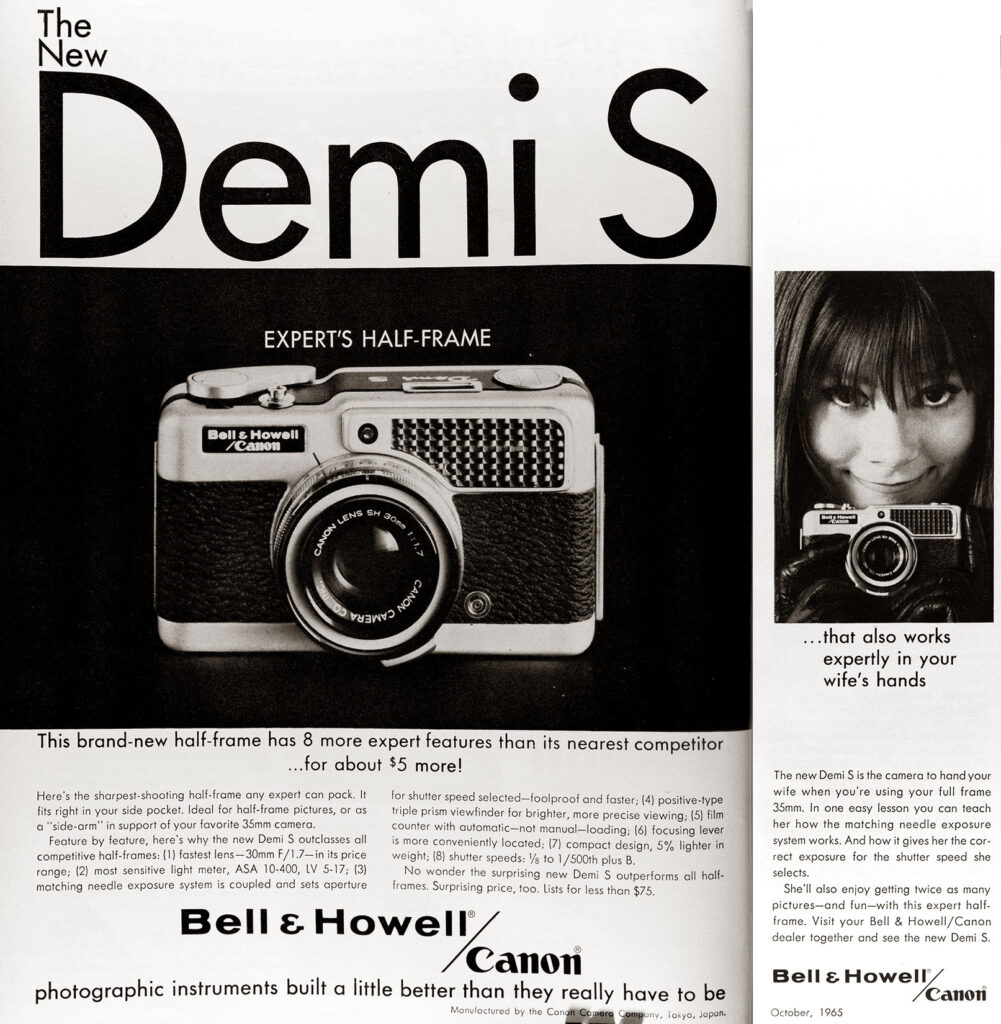

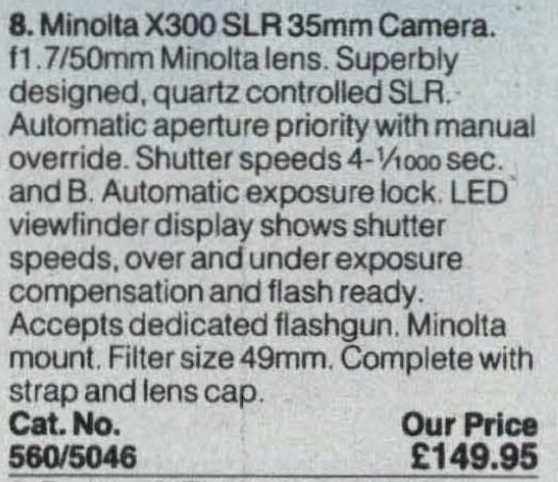

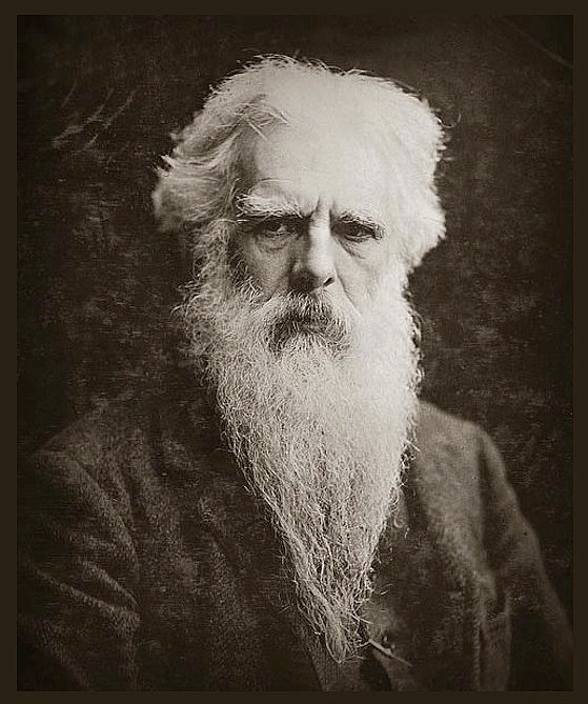

At the turn of the decade into 1980, camera manufacturers had begun to eat their own lunch. During the 1960’s and 70’s, compact cameras were generally marketed as “women’s” cameras in a style that only Mr Cholmondley-Warner could be proud of. They were “dainty things for dainty people” or, in the case of the more expensive options, for the discerning traveller. Either way, proper 35mm SLR cameras were manly things for manly men. Don’t believe me? Have a look at this:

Yep. The less said, the better.

These compact offerings were extremely simple cameras with a very limited feature set. Focus was often pure guess work or simply fixed at a set distance. Metering was limited to full manual (i.e. none) or set by a selenium cell meter coupled to perhaps two to three different shutter speeds based on the current it generated in a very simple circuit. In short, these were not imaging tools that were designed to give you flexibility, control and high quality images. Although, in the case of cameras like the Canon Demi and Olympus Trip 35, they really were surprisingly good despite their limitations.

SLR’s were the only option for anyone remotely serious about photography during this era and manufacturers were keen to ensure there was clear separation and differences in terms of features between their SLR offerings and their compact cameras. Traditionally, it had been easy selling SLR’s as an upgrade over anything else available whilst simultaneously opening up the magical add on revenue stream that comes with interchangeable lenses, flashes and other accessories.

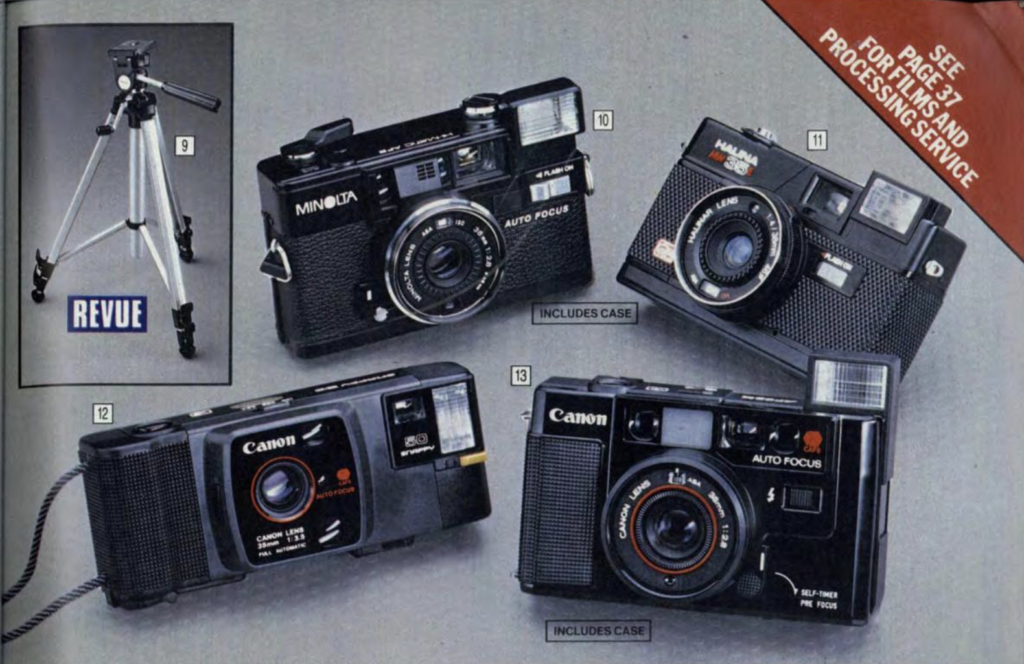

The only issue with SLR’s is that they were quite intimidating things to use for some people and the cost really was extortionate. From what little evidence I can find of average earnings and camera prices during 1970, to buy an SLR you were looking at 2-3 weeks wages for the average worker. So when in the 1980’s manufacturers suddenly started stuffing electronics inside compact cameras whilst simultaneously lowering prices, they quickly transitioned to being the compelling choice as the “every man” camera. Furthermore, because electronics were becoming cheaper all the time, devices were rather confusingly becoming more capable despite lower prices.

Compact cameras now had everything going for them. Not only were they extremely convenient, they were quite obviously superior in many ways despite the lack of interchangeable lenses. Almost anyone could pick one of these plastic marvels up and shoot to their hearts content. The exposures were normally fairly accurate, automatic flashes did a decent job of giving something usable from indoor shots and they were fully automatic – nothing to think about here.

The question now facing Canon, Nikon and others was one of how do you convince customers to keep paying high prices for the privilege of what boils down to lens choice and a better viewfinder? Sales promptly dropped through the floor as designers threw everything at the wall in an attempt to find out what would stick. For Canon, this meant the new T series

T is for Technology, and lots of it

Despite being the “official cameras of the 1980 Olympic Games,” and a sure sign of the pace of change, the stupendously successful Canon A series of cameras had begun to look tired and dated by the time 1983 came around. Styles, tastes and sweeping changes in technology were beginning to see things from TV’s to the humble kettle becoming obsolete overnight. No one wanted wood veneer or metallic finishes any more, plastic was in and lots of it.

Starting in 1983, Canon relaunched their entire FD mount camera range with the T50. The design brief was simple – create a camera which was modern, contained all the simplicity of a compact but with the benefit of an existing range of quality lenses. This was to be the most usable, approachable SLR made by Canon to date.

The T50 featured some “nice to have” things such as motorised film advance but just didn’t quite cut it in terms of tempting people away from compacts. There were some bizarre compromises – for example despite motorised film advance, it had manual film rewind and the T50 did not read DX codes on films to set the ISO automatically, something that (you guessed it) compacts of the time did do. In terms of simplicity, you cannot get more simple than the mode dial on the T50. There’s program, self timer and off. That’s your lot.

Canon completely missed the mark with the T50. Other than motorised film winding, this was effectively one of the earlier AV-1 cameras in a new body with none of the real control benefits of SLR photography for users to gradually grow in to as they learned. A year later in 1984, the T70 made up for many of the omissions in the T50 and was quite a compelling option for someone looking for a nice compromise between automation and control.

Each of the cameras in the T series feels like something of an experiment, each one designed to test the water and see what consumers really wanted and used in their cameras. Nothing says public beta more than the 1985 T80. In essence, this was a T50 compatible with a new range of three auto focus lenses designated “AC” and no one seems to know what that actually stands for. However, the T80 offered the one killer feature everyone wanted – auto focus, and it really wasn’t a bad effort at all. Although the lenses worked and AF was indeed convenient, Canon managed to ruin the camera they were attached to and the T80 too was doomed from the off to be a massive failure.

If the AC lenses had been bolted on to the T70, I think Canon may well have seen a greater deal of success. For all of the convenience of auto focus, the T80 offered none of the control over exposure that photographers actually wanted. What on earth Canon were thinking during this time is beyond me. In a search to win back customers by packing cameras full of technology, they had completely lost sight of what an SLR camera was all about – creative control.

Canon needed a miracle. Turns out it was waiting just around the corner in 1986.

A change of design language

Canon must have known they were in trouble. In the A series, Canon just released hit after hit, but the T series couldn’t have been more different. Nothing seemed to be working and they needed to compete with the likes of Nikon who were making loud noises about their forthcoming AF efforts. The Nikon F501 was about to debut in 1986 and it really was a capable camera with all the functionality photographers really did want. It would wipe the floor with all of the T series and Canon knew it.

For the first time, Canon hired a German industrial designer called Luigi Colani to help with the look and feel of the new T90. Colani was an absurdly talented and successful designer who started out in the automotive industry before branching out into pretty much everything you can imagine from kitchen appliances to a grand piano. His obsession was with natural, flowing lines and rounded edges. Everything he designed had his signature sweeping curves that made objects not only beautiful but tactile, ergonomic and desirable.

Canon threw the kitchen sink at the T90 and it worked. It worked so well that most of the design features on the T90 survived right up until the very end of film SLR production. The T90’s DNA flowed through every EOS camera that followed and none more so than the top end 1 series. If you’ve ever used an EOS 1 series of any kind, as soon as you pick up a T90 you’ll just feel like you’ve seen it all somewhere before.

It cannot be overstated how significant the physical design of the T90 was. Before this, cameras were functional, angular boxes with little serious thought paid to how they fit the hand, comfort during prolonged use or placement of commonly used controls. Even the T series itself had, until the release of the T90, continued the hard edged function over form design language that had persisted for so long across all manufacturers. For the first time ever, a manufacturer had taken the time to really think, to really consider how people used their cameras and create a product that delivered usability over anything else.

I could wax lyrical about the nuances of this design for an eternity, but it would be remiss not to acknowledge a few subtle yet important design features that made the T90 such a killer camera and so influential in future models.

From the front you can see the ergonomic grip which was so radically different from any that had gone before. The contoured placement of the shutter button is seemingly so obvious, yet had never been considered before. As the single most important control on any camera, it is almost baffling that such a thing hadn’t appeared anywhere else. The comfortable hand grip and shutter button layout places your hand and index finger exactly where they need to be, with the added bonus of security and comfort.

Next is the command wheel. Another first for the T90 and any Canon SLR. Now photographers were able to react to changes in each scene without removing their eye from the viewfinder. Well… almost, but more on that much later on. This was a camera that could be operated purely on touch alone, with no need to look at the controls, set them up and then recompose. It should be restated that this wasn’t normal, it wasn’t “the way” in 1986, it was a revolution and that’s what superb design is all about – you don’t need to invent something brand new to make something incredible but well thought out innovation can make every difference. In the T90’s case, these “small” things transformed the future of Canon SLR design.

From there, the “1 series” heritage is all here in plain sight. Multiple button presses are needed to change key settings, there is a hidden control flap on the one side hiding less commonly used features such as film rewind and drive modes. The LCD introduces the film indicator, complete with an animated line giving a relative indication of how many frames are remaining – something which remained in every 1 series camera which followed.

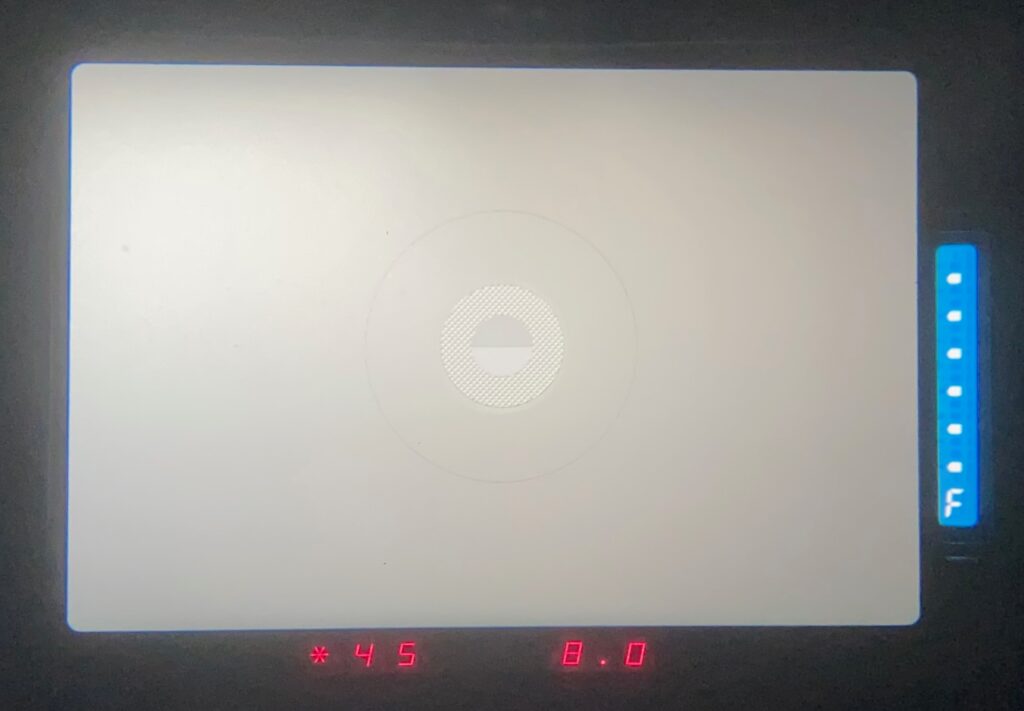

The T90 viewfinder is something special. Like most 35mm viewfinders it is clear, uncluttered and bright, but those glorious red LED numbers are so vivid, I much prefer them to the subtle green that took over in future models. On the right is another film scale showing frames remaining – this really was a camera that you just did not need to take your eye away from for any reason, everything was right there where you needed it to be until the film ran out. One more touch that is just above and beyond is that there’s actually a switch which either dims the brightness of the viewfinder displays or turns part of it off completely. That’s attention to detail.

Pro body, no AF?

We must address the rather large elephant in the room – auto focus.

It must’ve been quite confusing at the time for this revolutionary camera design to come along but yet still be missing the key capability of auto focus. All this technology, all this innovation and yet users were still expected to manually focus their lenses?

History shows us what was really going on. The attempt at AF in the T80 was definitely a sticking plaster and Canon obviously learned a great deal from that experiment. Considering the EOS line launched only one year after the T90 in 1987, there is no doubt at all that development of the whole EOS ecosystem had begun in 1985 at the absolute latest. Canon knew what was coming and this begs an intriguing question – was the T90 intended to be an EOS camera? Did they simply run out of development time and have to resort to the FD mount to get it out the door and revive sales? Perhaps the EOS electronics were too complex to add to the T90 body? Or was it simply that the professional, high end lenses were never going to be available in time for the EOS launch so it made no sense to wait?

Whatever the truth, we can be certain that Canon knew the T90 would be dead in the water within a matter of a year or two and it too was ultimately yet another experiment to finish off the rather odd T series of cameras with, only this time they’d pretty much nailed the design first time and the feedback from the T90 meant that realistically only minor tweaking to the concept was necessary as they planned the first EOS 1 series.

Retrospectively the lack of AF is the one thing that really does stick out about the T90. So much so that it takes a while to train yourself to not half press the shutter and then wonder why the image is still blurry and nothing is happening.

Common failures

The T90 has an unfortunate reputation for dying and this isn’t an uncommon problem. The T90 in the pictures throughout this review is not the T90 that I actually ended up using. Initially I had borrowed one from a friend to use, but upon taking it out the shutter failed to fire. This is the result of the classic “sticky shutter” problem which can be fixed if you’re skilled and patient enough. The fix for this involves almost a complete strip down to get to the shutter mechanism and is really best left to those who are experienced in these delicate repairs and know exactly what they are doing. The owner’s fix was “whack it” but I couldn’t face abusing a camera in order to use it.

The second issue that affects the T90 is the top LCD will eventually stop functioning. There’s debate as to how prevalent this problem really is, with some sources reckoning that every T90 will eventually suffer an LCD failure. Intriguingly the manual, from Canon themselves, states that the LCD will “become hard to read” after only 5 years!

Personally, and this is not in any way extensive research, I fortunately enough haven’t found one with a broken LCD yet. This failure doesn’t prevent the camera from firing off pictures but is obviously quite disabling when you can’t see what mode the camera is in nor how many frames you have remaining for example.

There’s no doubt that nearly all T90’s will suffer from some kind of failure during their life. The only hope is that you get the sticky shutter which can be fixed, should only need to be fixed once and will then give you probably another 30 years service before it decides to give up the ghost.

Ultimately, I went down the safe route and ordered a T90 from London Camera Exchange in Newcastle and apart from it turning up with expired batteries in, everything seemed fine. LCE, if you’re listening, I’d have thought a reputable camera store would’ve removed old batteries on principle as the amount of devices destroyed by leaky cells is unbelievable.

Driving a tank – Using the T90

Every other T series can be described as “kind of like an A series evolution but more plastic.” The T90 is like nothing else and for those who purchased one on launch, they must’ve felt like they’d just put their hands on the future. A fully working T90 really feels like you’ve taken a step forward, despite the reliance on manual focus, it is a really solid, reassuring camera to use.

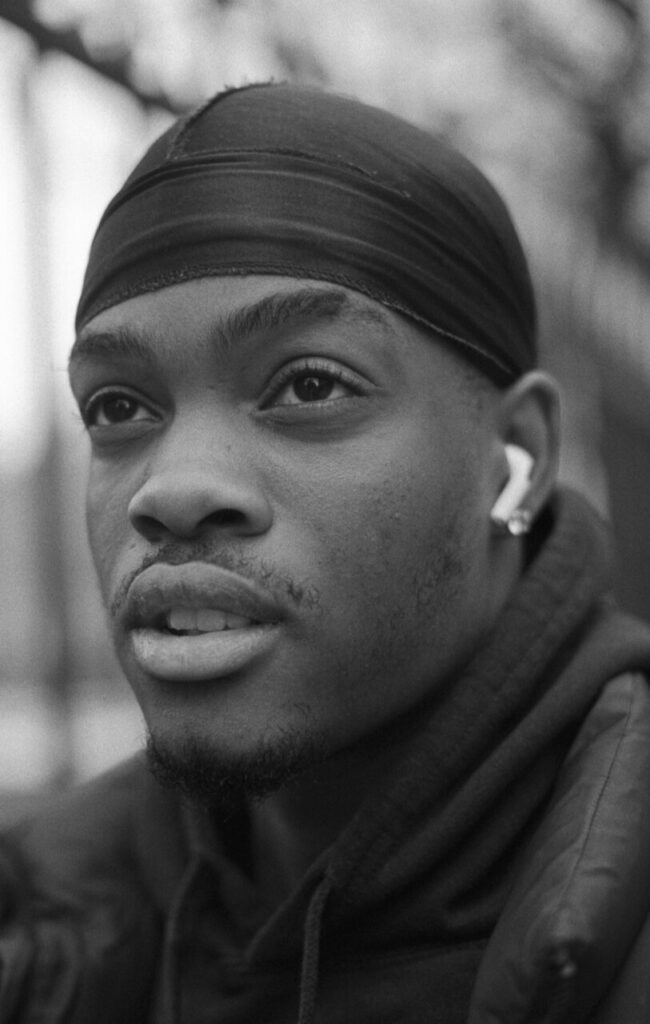

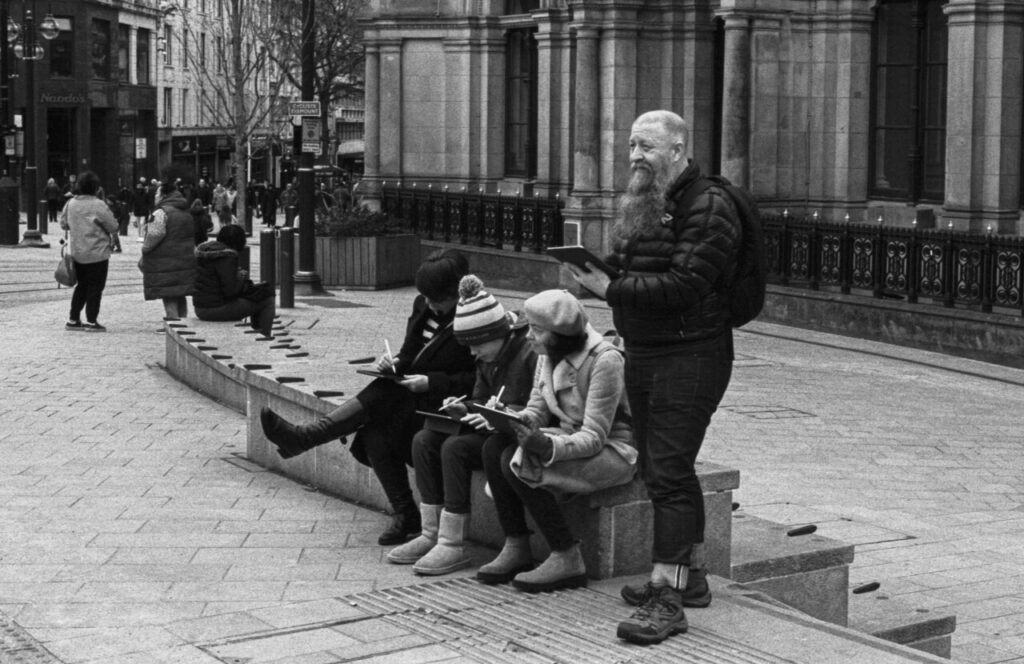

Out of nothing more than habit, I normally walk around with my cameras in aperture priority mode. The whole T series was sold on the premise that each body was packed with the best computing power Canon could fit in a film body at the time. The T90 was the pinnacle of this drive for automation and processing power and so, for the first time ever, I decided to put the camera into Program mode and just trust it to decide on the right exposure. All I had to do was walk around, focus and press the shutter.

It didn’t miss a frame. Not one. Every single shot in a roll of 36 exposures, whether it was worth keeping or not, was properly exposed. Moreover, the camera had chosen really quite sensible apertures and shutter speeds. When I paid attention through the viewfinder, it was averaging between 1/250 and 1/500 as a minimum and around F5.6-F8 which is pretty much perfect for taking pictures on the streets. The only time I overrode the program chosen was taking when taking a portrait and I pushed it a few clicks to a shallower depth of field. That’s it. I’m a total program mode covert.

I think Canon must’ve realised the viewfinder LED display consumes a reasonable amount of power because it turns off instantly after letting go of the half pressed shutter button. If I was to find one niggle with the T90 it would be the need to hold the shutter half pressed whilst scrolling the wheel to change settings. If you don’t hold the half press, the setting will change but you won’t see it because the viewfinder display has turned off.

You can use the LCD at the top of the body to an extent, but this doesn’t show shutter speed in program mode, for example. It’s surprisingly difficult to balance the shutter button with one finger whilst scrolling with another. To do so is extremely unnatural as the wheel is behind the shutter button, meaning you’d have to balance it with your middle finger whilst scrolling with your index. This is odd to say the least.

The shutter is lovely. It’s not 1 series lovely, but it’s certainly a step up from any A or T series and the response time seems to be much quicker than earlier cameras from the time. Focussing is absolutely identical to almost every other FD body, I can’t really tell the difference between the viewfinder on the T90 and the AE-1 Program.

The T90 is packed with features I didn’t make much or any use of. There’s a fantastic idea called “Safety Shift” which is where the camera allows you to put in the settings you want but if it thinks you’ll miss the shot because of poor shutter or aperture choice, it will “shift” the exposure to a different program so you stand a better chance of getting the shot you wanted.

Safety shift, combined with an awesome high FPS mode (no, I didn’t make another film GIF after the last time…), three metering modes and a really quite accessible multi-exposure mode all go to show what a professional tool this was and the time and effort Canon engineers put in to make this a truly dependable, well thought out professional camera.

Conclusion and legacy

The importance and influence of the T90 simply cannot be understated. There are so many small, subtle parts of the T90 that went on to feature in EOS series cameras for decades, other than the whole ergonomic “natural curves” design language introduced by Luigi Colani. The only feature I wish hadn’t been carried forward to the EOS 1 is that horrible side door on the palm grip. On the T90 especially, this is constantly flicking about the place as you put your hand on and off the body. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again – there had to be a better way of hiding these buttons or at least to put a catch on the door.

The build quality, despite failures 30 years down the line, is wonderful. Canon really hit the design jackpot with the T90 and it looks the part – it is undeniably a beautiful camera. The weight of the body can be described as “reassuringly heavy.” Later professional bodies will pull your wrists off if you hand hold them for very long, the T90 is just balancing on the edge of being weighty enough that you know its there but not overbearingly so. At a push, if you have one with a stuck shutter and no way of repairing it, I reckon you could use it as a reasonably decent hammer.

If you want to feel like you’re shooting the Rolls Royce of manual focus cameras, you really cannot do better than a T90. I very quickly fell in love with mine and I didn’t think I would at all. There is one glaring problem, though.

The T90 is such a weird juxtaposition of old and new that at times I had to remind myself to focus manually, it looks, feels and behaves like a camera that can and should do everything for you and this is the big question – because it is a manual focus body, do you need a T90. What is its purpose?

If you love the manual, analogue experience of old cameras then you’re going to feel right at home with a Nikon F series, or a Canon A series. They’re the sweet spot of manual – they feel like they should be manual focus, yet have a tiny sprinkling of technology in there to bring them out of the dark ages of cameras with built in light meters and maybe a program mode – they offer just enough, in other words. Do I ever miss an LCD display on top of my AE1? Never, the thought never even crossed my mind. Do I miss motor wind and automatic rewind? No, in fact I’d go so far as to say the manual film advance lever is one of my favourite photography experiences of all time.

Then what does the T90 bring to the party? What about the “professional experience?” Well, it definitely makes you feel like you’re in the presence of camera royalty and no doubt it’s got more features than the average person needs but personally, if I want the professional experience, the “best of film” then I’m going straight to the EOS 1 series all day long.

It is important to remember that with film, the camera adds absolutely zero to the image quality, this is solely a lens thing. I can take the beautiful FD 50mm 1.4 (a revelation, I must say) and bolt it to my AE1 Program and achieve identical results to the T90. That set up gives a wonderfully compact, lightweight, “comfortable for the whole day” manual film camera experience. The T90 is an ergonomic wonder, but an ideal street camera it isn’t.

Ultimately, I think Canon knew full well that the T90 was a dry run for the EOS 1. It leaves me deeply conflicted, on one hand I undeniably love everything about the T90 from its history, design, features, ergonomics to just how it looks. On the other hand, I cannot think why I really, really need one – it just sits in this grey no mans land between manual and auto focus. Will I keep it? Honestly, I don’t know. Should you buy one? Yeah, you really should. See – conflicted.

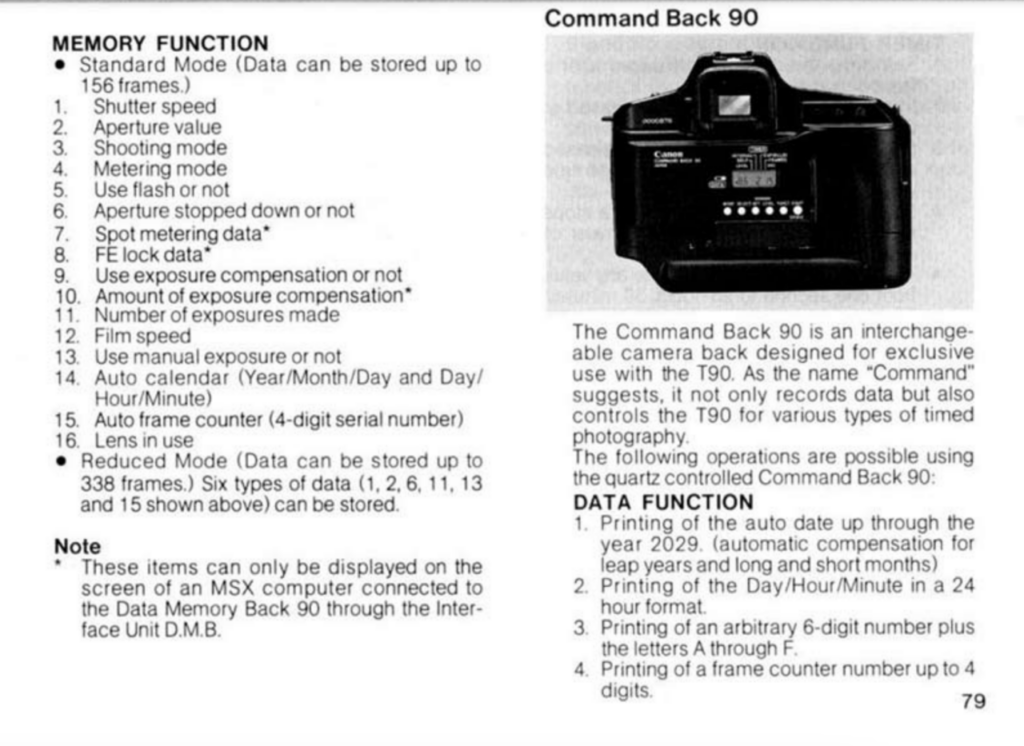

There is some really bad news, however, for those dedicated Command Back 90 users. If you’ve got one of those, there’s only another 6 years left before your auto date stops working. I’m not sure what should worry you more, the fact the date won’t work, or the fact you’ll need to use an MSX to control it. I’d love to know if anyone actually tethered one of these to a real MSX in the day, what an absolute gem of a setup that would’ve been even though I cannot think what possible benefit it had in real world use.

And before you ask, no, I can’t afford to make this happen… although you bet I just found out that Canon made their own version of an MSX for this very purpose….

Share this post:

Really enjoyed this. Very well-written. I have a lovely fully functioning T90 – the stuff of my boyhood photographic dreams. I regularly half-press for AF, too!

Thanks for your comment. I think that’s half the attraction of film photography these days – we can go out and buy what were once £2000 cameras and really enjoy the best there ever was.

I used T90s for many years. The lack of autofocus was not really a ‘thing’ as I had a large collection of FD lenses and SLRs simply were not autofocus in those days. The only time that I had one fail on me was when I dropped it from about 20′ onto a stone floor in Pompeii – that did finish it.

So good was the T90 that I skipped the autofocus/film generation entirely, jumping to digital only with the original 7D (although I had been using 30Ds for work for a while by then).

Incidentally, I never had a problem with the button flap opening other than when I opened it quite deliberately … maybe the one on your’s is a bit worn and loose.