A couple of weeks ago my fridge was looking rather sad and empty. The film shelf was down to the last few rolls and it was time to stock up again whilst I still had the money before the cold sets in and I have to divert cash to inconvenient things like making sure the kids don’t freeze. Despite rising prices and inflation hitting seemingly everything in recent months, film prices had remained fairly static over the summer months and whilst not cheap as chips, prices were acceptable. Well, I say acceptable, it is still possible to buy a film SLR for the same price as a single roll of film.

Things have clearly caught up with manufacturers and distributors. Rising costs for raw materials and transport are surely to blame for recent rises, but where do these costs come from? What goes in to making a roll of film and what does it really cost to shoot film these days?

In this post:

We had it so good

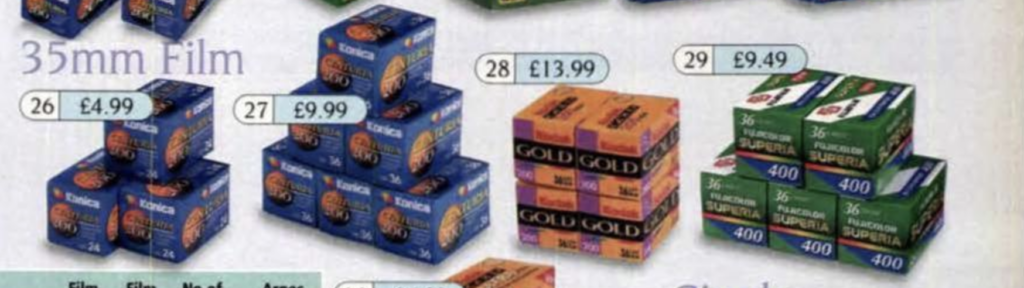

Although digital cameras began to appear in the very early 1990’s, it wasn’t until around 2004 that their adoption became mainstream and affordable. Film had a long mass market life span. If we make the assumption that film prices would’ve been at their lowest during this 1990’s peak, it would make sense to check whether prices really were rock bottom during this time before drawing any comparisons to modern times. I dug around Argos catalogues on the Internet Archive to get a feel for what prices were like when film ruled the roost.

Whilst not exactly a comprehensive or scientific piece of research, I settled on “Konica ISO 200 Colour Film” simply because it’s the only film that Argos consistently sold across a decade and so gives a reasonable basis for comparison. Here’s what I found:

| Year | Cost per film | Cost per frame | Inflation adjusted (2022) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | £2.15 | 5.9p | £4.51 / 12.5p |

| 1993 | £2.10 | 5.8p | £4.18 / 11.6p |

| 1996 | £1.99 | 5.5p | £3.58 / 9.9p |

| 1999 | £1.67 | 4.6p | £2.85 / 7.9p |

When adjusted for inflation, we discover that it wasn’t that cheap to shoot film in 1990, but prices descended rapidly approaching the millennium. I’d give anything to be in the fortunate position where film photography was 8p per shot today.

It is important to remember that this is for colour films. These now cost an absolute fortune and the cheapest Kodak 36 exposure, ISO 200 film I can find today is £10 per roll. If you want to shoot Kodak Portra, get ready to take on a second job because that’s £16 a roll for ISO 400. Respectively, you’re looking at 27p and 44p per shot and we are not even taking developing costs into account. Yet.

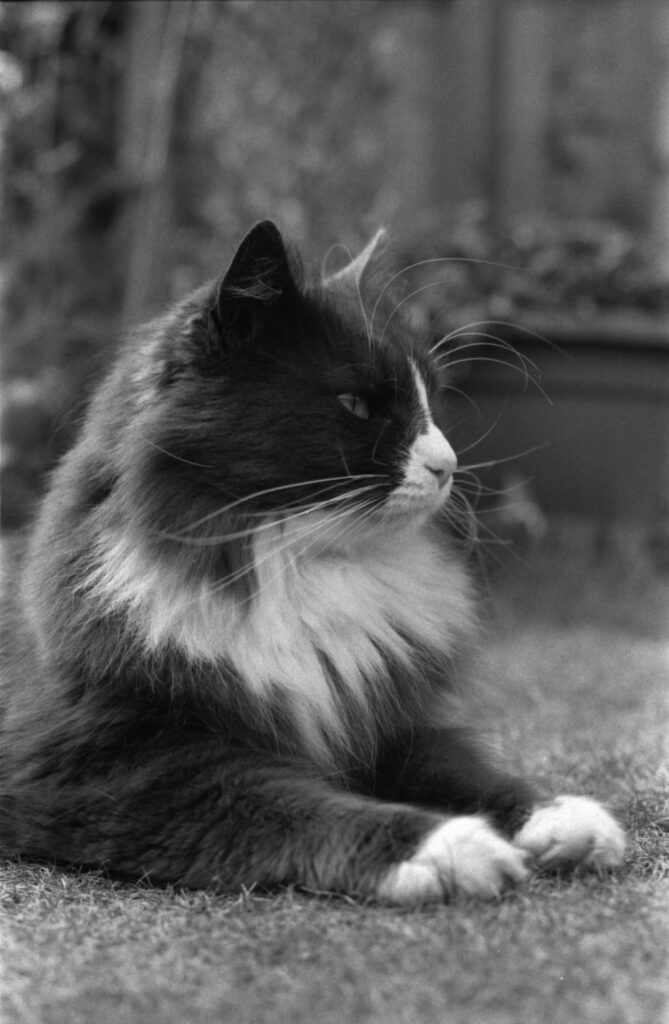

Black and white is a more interesting comparison. The cheapest black and white film is, at the time of writing, £4.65 for a roll of Kentmere 100 or 400 which sits firmly in the “prices from 32 years ago” category. In context, that’s not at all bad, is it? In 1990 there would have been far, far more market competition helping to drive prices down. Now, there are few large names in the film manufacturing market coupled with much lower global demand. I think it is quite incredible that we are still able to shoot film at a comparable price when essentially the mass market has all but gone.

What makes a roll of film

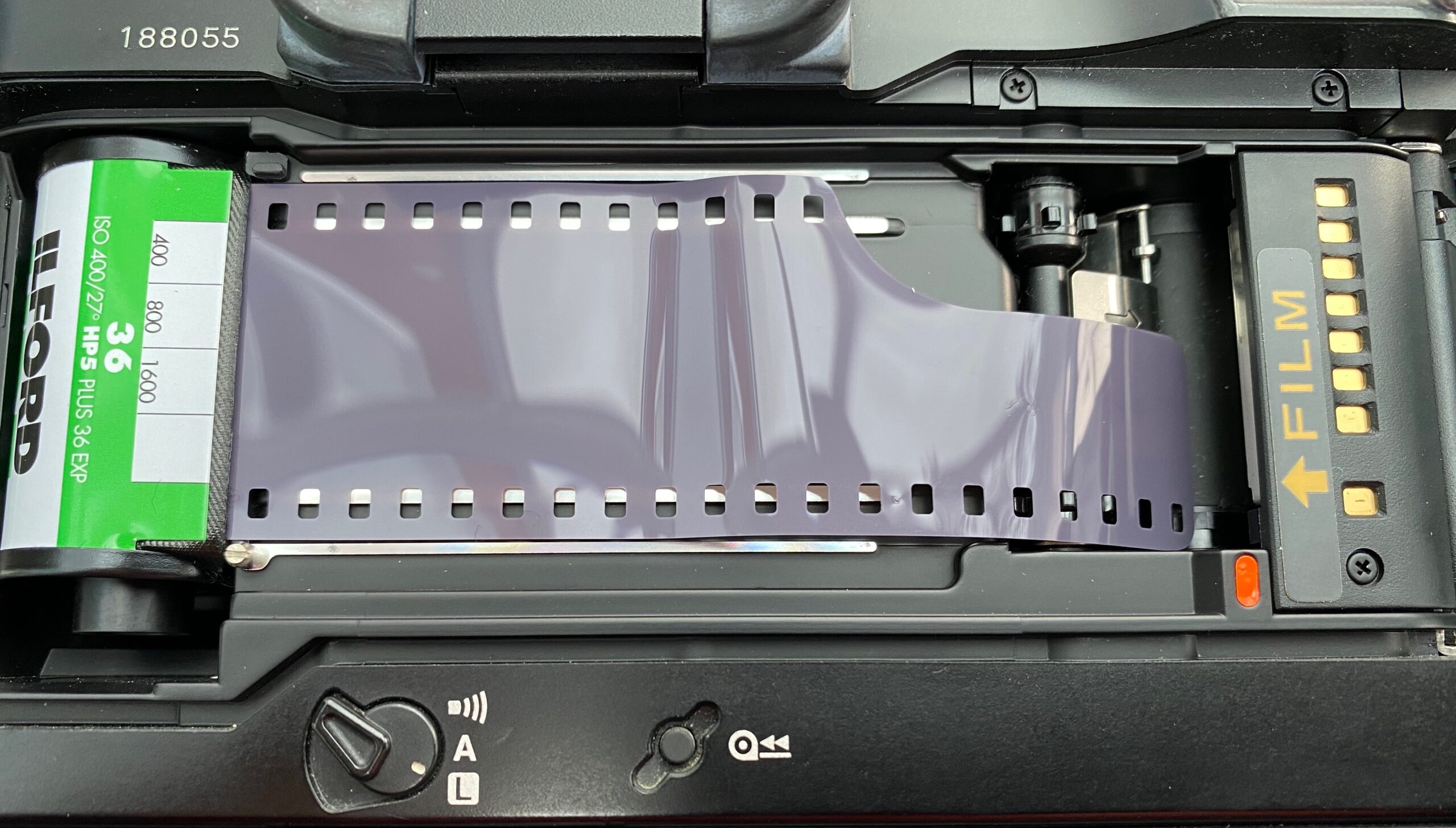

When considering how reasonable the price of any commodity is, knowing what actually goes in to the manufacturing process really helps to make a sound judgement. Luckily for us, the good folk of Ilford have made a video documenting the process.

I learned a lot whilst reading up on the chemical processes involved in creating film. I knew the basics – silver halides are light sensitive, they’re mixed with a few other things to make an emulsion and this is then spread evenly over a cellulose acetate base to create the final product.

Although a massive simplification, these are the main parts of any modern monochrome film. One thing I didn’t know is that the main ingredient in the emulsion, other than silver halide, is gelatine. This is a byproduct of the meat industry and means that your film is made out of mashed up pigs. How odd?

The Ilford video shows that although the process is quite straight forward, the machinery and science behind it is relatively complex. It would appear that the actual emulsions are made elsewhere to their specifications but everything else is done “in house.” Using Ilford as an example is quite useful here, they’re a company based in England and so they’re directly affected by everything that is murdering our economy at present.

My “back of a fag packet with a GCSE in Business Studies and a finger in the air” best guess is that Ilford will be most effected by the prices of raw materials, mainly those three key components – silver, gelatine and acetate. Silver prices are relatively stable short of a global crisis and, as an aside, is hideously under priced versus the global demand for it. Most investment firms believe the price of silver will eventually rise rapidly when global supplies begin to dwindle and the main source of silver switches from mining to recovery from other sources.

Gelatine is the surprise factor. Farming costs have gone through the roof in recent years and it is well documented the problems that farmers face with feed prices. They’ve been hit twice by the rising cost of farming since the UK left the EU and also the soaring cost of grain due to the war in Ukraine. Anything that increases the cost of meat production is going to be directly passed on to consumers. Although Gelatine is a byproduct of the meat industry, global demand is absolutely staggering. According to this website, the market for Gelatine is worth $5.8 billion and is expected to grow over the next 10 years by almost 10%.

Combined with rises in costs for transport, fuel, energy and the need to pay wages that can cope with inflation, I’d presume that Ilford have seen a rise in their base costs the likes of which they haven’t seen in living memory.

Recent rises

I shot the last of my rolls of HP5+ in my recent EOS 1n review and considered buying some more to keep my shooting and developing process a little more consistent. In terms of price, it used to be the case that Foma film was the absolute cheapest, then Kentmere (made by Ilford) was within a few pence of that and then Ilford films would be a pound or so more expensive still.

Last year, a roll of 36 exposure HP5+ was £5.65, Kentmere 400 would set you back £4.15 and Fomapan 400 £4.10. £1.50 is still a reasonable premium for the Ilford name and associated quality, it certainly begins to add up as you shoot more film. As late as June this year, those prices were still the same, however as of October, a roll of HP5+ is… £7.15.

Christ.

That price level puts it almost up there with shooting colour. Suddenly, the value aspect of black and white film has disappeared and I’m left wondering what possible benefits there could be for paying this amount for a film. Right now, I cannot think of any. Comparatively, Kentmere 400 has only gone up by 50p per roll. I’m sure you can guess which film I’ve switched to as a result.

Perhaps I’m analysing this at the wrong moment in time and the price rises affecting Kentmere haven’t filtered through to the consumer yet. As it stands, however, I cannot really understand why a roll of Ilford HP5 is verging on twice the cost of a roll of Kentmere. They’re made in the same factory, by the same company, using very similar emulsions (although they insist they are different). I cannot tell you visually what the difference is between the two. Furthermore, HP5 is not a premium film, it is the Delta range which uses a different form of emulsion that is meant to give finer results. A roll of Delta 400? £8.15…

This is a fairly sad moment, having shot Ilford films for over 15 years now, I think I’ve already put my last roll through a camera for the foreseeable future. I don’t have the equipment, skill or eyesight to justify the price of their films any longer.

Let’s do some maths

Until now, I’ve conveniently avoided the cost associated with getting the images off the film and either printed or scanned. In the heyday of film nearly everyone would have opted for development and prints when having their films developed. I doubt anyone in the 90’s had a decent film scanner other than professional photographers. However, to keep things fair, I’ll compare just the cost of processing/developing a film.

Keeping things simple, because I’d spend all night on a search engine otherwise, I went back to Argos for historic pricing and found the cost to develop a 36 exposure roll of colour film in 1999 was… £2.89. Inflation adjusted, that’s almost exactly £5.

I did a basic search for 35mm developing costs today and found the following prices for development only:

- Analogue Wonderland – Colour £5, B&W £7.50

- Asda – Colour £5.75

- Photo-Express – Colour £4

- FilmProcessing.co.uk – Colour £5.85, B&W £9.17

That’s enough data to make a quick and dirty consensus that colour developing is now £5 ish (exactly the same as it always has been) and black and white will set you back at least £8 per roll.

If you’re going to shoot colour today, there are no cheap options. Home development kits for colour are anything from £35 all the way up to £80 for a kit containing the necessary chemicals. If you develop in batches of 20-30 films then this would be ok, but I can’t say this is convenient. In this context, the £5 developing cost is absolutely acceptable. The C41 process is so well known and all labs will use automated machinery meaning your results will be spot on almost regardless of where you go and also explains why the cost now is the same as it always has been – we’re using the same kit!

But what about black and white? After all, it’s by far the cheapest film to buy in the first place. The development costs for monochrome reflect the fact that this uses different chemicals and probably involves more human interaction to develop. At £8 a roll you’re soon on your way to paying off the cost of chemicals, developing tanks and other bits and pieces you need to just do it yourself. You can easily get a Paterson tank for £10 off eBay and a bottle of developer will cost no more than £10-15 a bottle.

Some quick maths for my development process looks like this:

Rodinal developer is £13 for 500ml. My tank uses 460ml of developer per film, at a ratio of 1:25 (although you can go 1:50 without issue). That’s 17.5ml of developer for each film, so 28 rolls per bottle, making it 46p per roll in developer costs. This could be as low as 24p per roll if I were more patient and did 1:50.

The only other thing you really need is fixer. Fixer is £12 a bottle and goes off after a while, I tend to get about 3 mixes out of a bottle, but that will then develop many, many films as its reused. I can only estimate that conservatively, I’ll get 10 films (its much more) out of a mix, so 30 per bottle making it 40p per film.

Home development is currently costing me 86p per film. If we add on the cost of development to the cost of the actual film I arrived at the following:

Kentmere 400, 36 exposure = £4.40 + 0.86 = £5.26 / 36 = 14.6p per frame all in.

If I were to send these films off to be developed I’d be looking at a minimum of £12.40 per film or 34p per frame all in. That’s a significant premium, but nothing compared to colour which would weigh in at £15 (minimum) or 41p per frame all in. Shoot the God of colour, Kodak Portra, and you can expect to be in for approximately 64p per shot. Madness.

Conclusion? The cheapest possible way to shoot film today is black and white and to develop it yourself. If you’re patient, you’ll easily get the cost down to 14.00p per frame if you’re patient and use less developer. If you stand develop then it’d be even less.

Second conclusion? Shoot colour only if you’re loaded or bonkers.

Third conclusion – the total cost of shooting film is remarkably close to prices from 1990!

Future proofing

I looked at bulk loading film recently as a method of saving money over time. Sadly, the numbers don’t add up once the equipment is factored in. A bulk loader and some reels will cost anywhere around £30-40 and a 30m roll of bulk film is currently £60.75 (Kentmere 400). This should yield 20 rolls of around 30 exposures – this varies according to the loader and reels used and works out at near enough £3 a roll.

These are rough calculations, but that saves approximately £1 a roll, meaning you’ve got to bulk load near enough 40 rolls before you start to make any money back. I’m not against this idea, but the initial outlay of £100 all in and £60 each time thereafter is prohibitive at present. It is something I’d like to get into in future if funds allow, because being able to roll any length of film you like is superb, sometimes I’d love to have just 18-20 shots on each roll so I can get frames through the developing process more quickly. Conversely, if develop more often then I’m being less economical with developer – the cost/benefit here is really quite nuanced.

Finally, there’s the “drip feed” approach that I think I’m going to end up relying on for the foreseeable future. Film keeps for a very long time in the fridge and this is how the emulsions and manufactured films are stored by Ilford. It should be the case that film kept in a fridge will last long enough that it never starts to go bad before you’ve had the chance to use it. If you need more time than this, apparently a Kodak employee suggested that film kept in a freezer could easily last 18 years before degradation sets in.

The answer, then, is to just buy film regularly, as and when you can afford it without waiting until stocks have run out and you need some there and then. Psychologically this works because you soon forget how much you spent on the last batch of film, it’s just there ready to be used. This helps remove that “oh my god each frame is costing me 50p” mentality that may mean you miss a shot for fear of it not being worth it.

Anyway, if anyone fancies sending me a bulk loader, I wouldn’t say no…

Share this post:

Interesting article, you’ve clearly done your research!

Some things to add:

– I keep all my film in the freezer and pull out a roll a couple of hours before I want to use it. I stocked up last summer on 120 Portra. I doubt I’ll be buying it once I’ve finished that but as I only shoot a few of those a year I should be alright for a while.

– I have done colour developing at home and it is quite easy, but you do need to do enough films to make it cost-effective. Also, I would factor in a sous-vide for keeping the water to temperature. Not absolutely essential, but it makes life easier.

– I test my B&W fixer every time. Drop the film leaser in a small bit of fixer and see how long it takes to clear. If it’s less than 2 minutes the fixer is good. Mine keeps for longer than 6 months in air-tight bottles.

– another disadvantage with bulk loading is that canisters can leak light, so I’ve always steered clear, the economics don’t work for me.

Great site, glad I found (via a sponsored link on Instagram). Keep up the good work!

Malcolm

Thanks for your kind words, some really useful information there – especially about freezing! Glad you enjoy the content.

There IS a way to shoot colour film cheaply. Shoot Vision 3 and all its remjet removed variants. Avoid Cinestill, they’re overpriced. Taobao is your friend. You can get some for quite cheap, prices on Taobao hover around the 13 Singapore dollar mark including shipping.

True, there are options like this but it isn’t exactly cheap. A roll of Vision 3 or similar is approximately £7.50, which at first seems reasonable, but factor in the development kit at £40 (plus you need something like a sous vide for temperature control) and you can only get 15 rolls out of 1 litre of developer and suddenly it isn’t so cheap any more. Additionally, a bottle of Rodinal or similar is about £12 and it will develop you 55 films without going off – black and white is miles ahead in terms of practicality and value. Colour developer doesn’t last stored in open bottles so to achieve that maximum value for money, you’ve got to develop 15 films in a row, setting you back about £2.65 per film in costs. Whilst cheap for colour development compared to commercial offerings, it still isn’t practical.