2024 update: I recently bought the standard battery grip and went through the process of converting my 1N-HS into a 1N, it’s worth reading my experiences there alongside this review – that should give a complete picture of the whole 1N experience in all configurations.

Original review:

It was inevitable, wasn’t it? Following my first ever experience of 1 series Canon SLR’s in the form of the 1D Mark IIn, I knew I needed to return to my film roots and pick up an EOS 1 film camera. Whenever I shoot digital, I enjoy myself but it almost feels like cheating at a video game – it’s still fun, but the sense of achievement is lessened.

A few months back I made a bold claim that the Canon EOS 50/55 is all the film SLR most people will ever need and the best value to boot. Going out and buying not one, but two 1 series cameras in a row after that is going to take some explaining, isn’t it?

Let’s give that hole a dig and see where we get.

In this post:

- Buying in to the top end

- First impressions

- Familiar Controls?

- The anti-battery grip

- Shooting some rolls of film

- The worlds most expensive GIF?

- Day and Night, Literally

- Conclusions and Learning

Buying in to the top end

Deciding which 35mm EOS 1 to buy is a surprisingly simple decision compared to their digital counterparts. There were only ever three models of EOS 1 – the original, the EOS 1n and the EOS 1v. The EOS 1v is undoubtedly the king of 35mm and the pinnacle of everything Canon ever did with a film camera, but the price reflects this. There are no 1v’s for anything less than £400 right now and that price point puts them firmly in the “collectors only” bracket. That leaves the original and the 1n to choose from.

The original EOS 1 came out in 1989 very early on in the life of the EOS series. Following the design language and build quality of the much loved T90, it introduced a compelling choice for professionals looking to move to Canon’s latest and greatest AF based eco system. The EOS 1 still holds its own as a film camera today and there is very little wrong with it, but based on current second hand prices the difference between that and the much later, more capable EOS 1n means that right now the choice is obvious – if you’re going to buy a 1 series film SLR and don’t have bottomless pockets, then a 1n it is!

But why? Why does anyone need to spend large amounts of money on an old, outdated film SLR when, as mentioned earlier, there are super capable options like the EOS 50 for far less? Well, if you haven’t already, you really should read “what it means to be one” to really get the background on why buying one of these cameras really makes a difference, or is at least so desirable to film shooters like myself. Go on, I’ll wait, I’m patient like that.

Back? So now we know the lure is basically a mix of je ne sais quoi and effectively wanting to know what it felt like to be a newspaper photographer in the 1990’s. Curiosity is an expensive emotion and keeping that expense down as low as possible was the next problem to solve. What is an EOS 1n really worth today?

The EOS 1n was released in 1994 and finding the UK launch price is really quite difficult as everyone just seems to quote the Japanese launch price of 215,000 Yen (which in turn is quoted from the Canon camera museum). Doing some digging, the exchange rate in 1994 was approximately 155 Yen to the Pound, making the EOS 1n approximately £1400.

This seems to be about the right ballpark for what was the best of the best available at the time and is in line with future one series EOS cameras. Going on my experience with the depreciation of digital bodies, I’d have expected the film equivalent to come in around the £100 mark, although “the market” may have something to say about that.

Any Canon camera with a 1 in the name is not cheap, even 30 years after their launch. Strangely, prices for the EOS 1 and 1n are almost identical and that doesn’t make much sense as there are some significant differences between the two. The only thing I can think here is that due to their age and original expense, there are fewer about due to the action they inevitably saw and mechanical failures are bound to happen, hence both are now in the same ballpark in terms of availability.

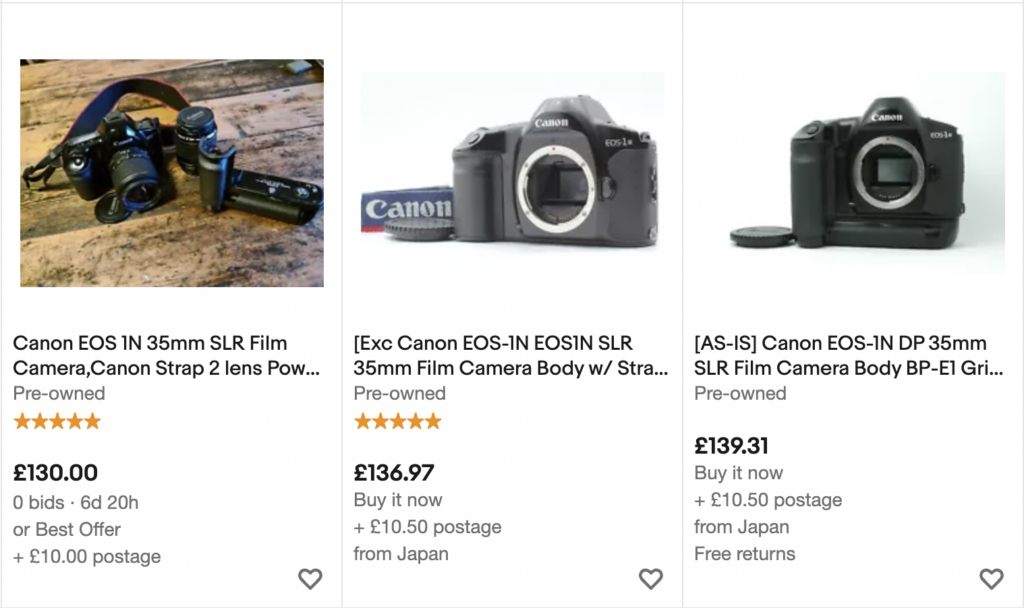

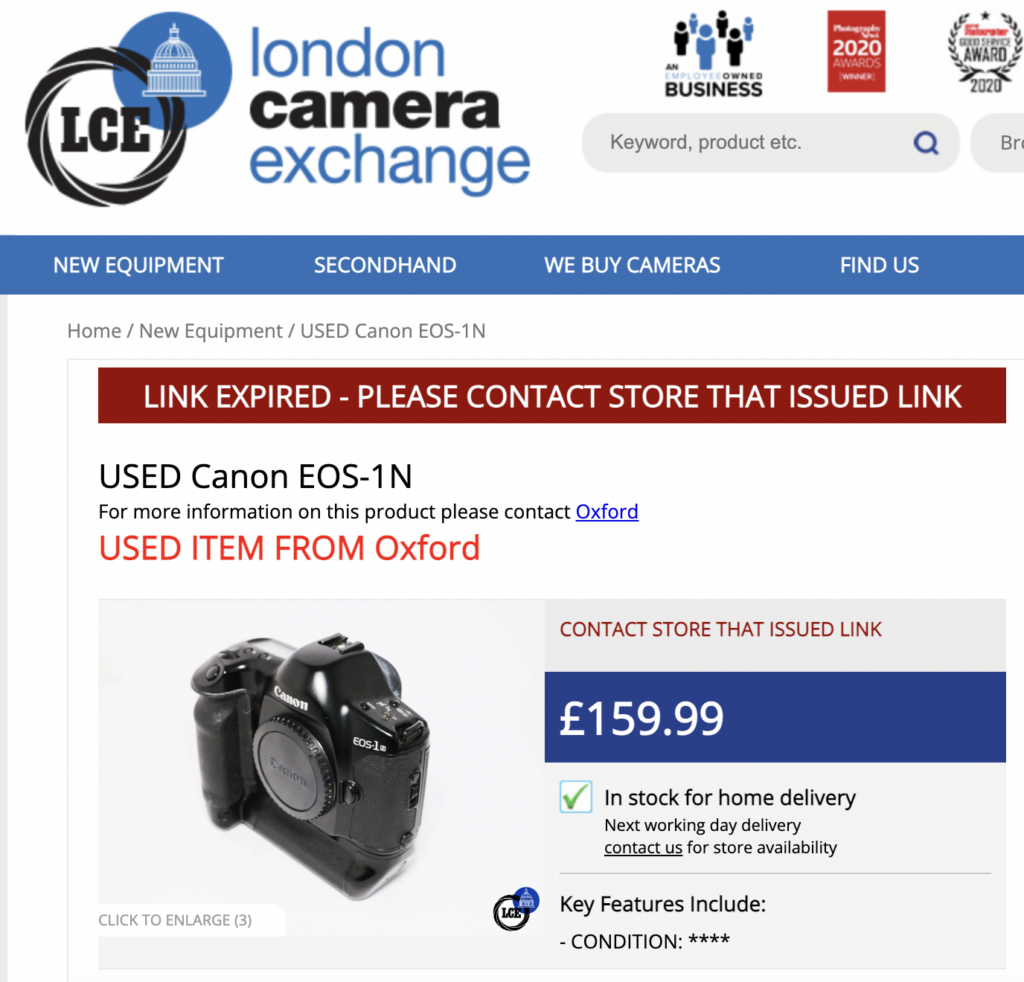

The next thing I learned was that eBay is definitely not the way to go for these cameras. This happens when something becomes more scarce, people just try their luck with prices that have no resemblance to the real world worth of an object. When that happens, it’s time to walk away or go elsewhere. Moreover, the models on offer are nearly exclusively sold from Japan which brings with it a world of risk and potential for things to be lost in translation. After some searching, I found this from the London Camera Exchange:

At a penny under £160 it was a way past the original budget of around £100 I’d had in my head at the start of this adventure. Having looked almost everywhere, this really was the best value in the country that I could find and LCE have an excellent reputation so I had no reason not to trust that this particular body would be in great condition, safely sent and I could very easily send it back if there were any problems. The slightly higher price also accounted for the power winder/battery grip which enables 6fps. Who doesn’t want to smash out a whole roll of film in a little over 5 seconds?

Actually, that’d cost more than £1 per second at current film prices. Perhaps not the best idea.

First impressions

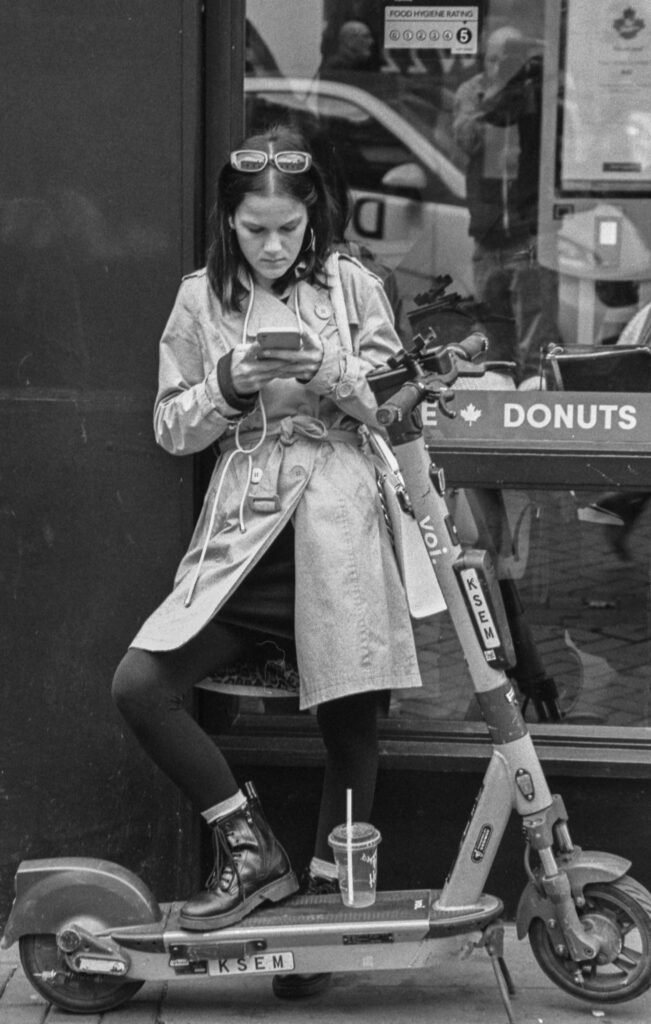

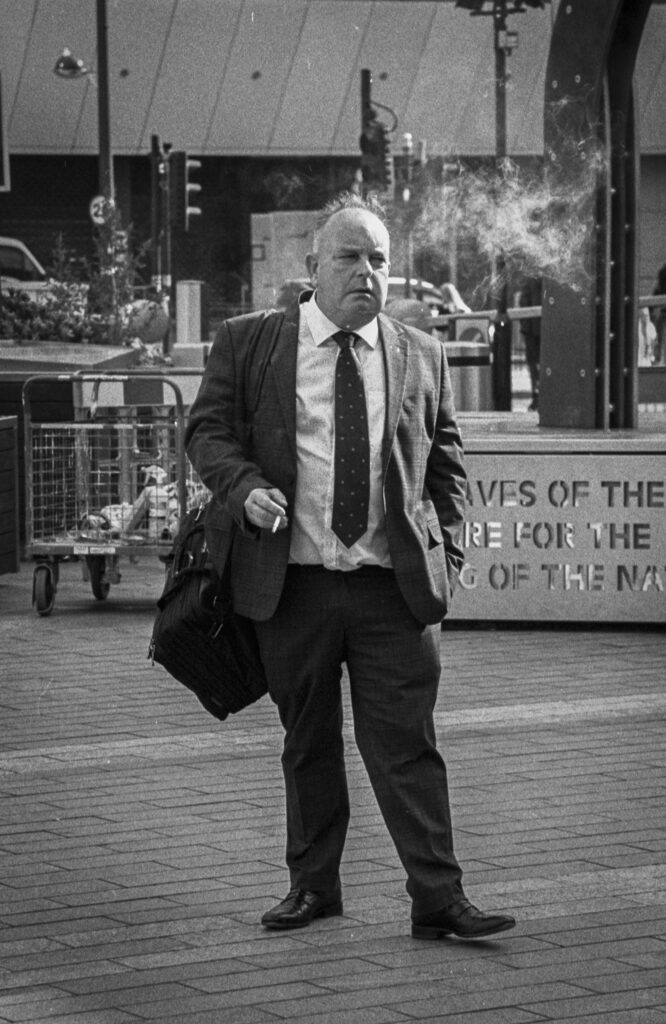

On its own, the 1n cannot be described as a small camera. Compared to other models, this body is all round more chunky, more robust and just… bigger. My 1n is even bigger still because of the power winder and vertical battery grip attached to the bottom of it.

Canon differentiated the 1n into three options, the base 1n was the camera body only and could achieve 3fps continuous burst shooting. It used a 2CR5 battery which fitted in the hand grip on the right of the camera and that would be good for at least 50 rolls of film. I don’t know about you, but I’m not feeling short changed there.

The next option was the 1n-hs, which is the model I have, this removed the 2CR5 battery and replaced it with a vertical grip that takes no less than eight AA batteries. With this installed, you upgrade to 5fps continuous shooting and can achieve approximately all the rolls of film in the world before the batteries are exhausted.

The final option was the “RS” model that, for want of a succinct description, did away with the mirror blackout when you take bursts of pictures and upped your frames per second to 6. No one but sports photographers ever bought one.

There’s no getting away from the basic fact that this is a big and extremely heavy camera. I made the mistake of forgetting my camera sling and then walked around Birmingham for almost 3 hours with it. By the end of that particular trip I needed new wrists. If you do use a decent strap or sling, then obviously the weight stops being a problem, at no point did I ever feel like it was burrowing through my shoulders when worn in that way.

Familiar Controls?

There was a lot of design language transferred from the EOS 1 film cameras to the EOS 1d digital bodies. Part of me wishes I’d tried this film body out before moving on to the digital version because although there are control differences, the step up from any other EOS film camera to the EOS 1 series is really quite an easy learning curve. The step up from any EOS digital body to an EOS 1d, on the other hand, is like learning how to walk again.

Although Canon incorporated a few methods of preventing accidental setting changes, the controls are obvious and being a film camera, there are far fewer controls or options to change than on the equivalent digital body. The only time I became confused during use was when I’d somehow dialled in some exposure compensation and couldn’t for the life of me get it out. It turned out I’d physically switched off the quick control dial on the back of the camera…

Other than the mode change buttons on top of the body, there are some special secret hidden functions behind a flap on the right side of the body. This flap doesn’t clip into place because it would otherwise prevent the film door from opening – it neatly folds out as you open the back of the camera. However, this does mean that if your hands get slightly sweaty or you’ve got something on them, it has a habit of opening itself which can be slightly disconcerting. On a professional body, I’d have expected a slightly better design choice here as it seems an obvious place where dust and weather can get inside and start causing issues.

Overall I like the design of the 1n and almost instantly felt at home using it, apart from one small detail with that massive battery grip…

The anti-battery grip

On all Canon digital SLR cameras, the optional battery grip simply clicks inside where the battery normally goes. You unclip the battery door, store it in the handy compartment and screw the battery grip in to the tripod socket. On the 1 series film SLRs they took a different approach where the entire grip comes off underneath the shutter button. It reminds me of the bit in Terminator 2 where half of Arnie’s face has disappeared.

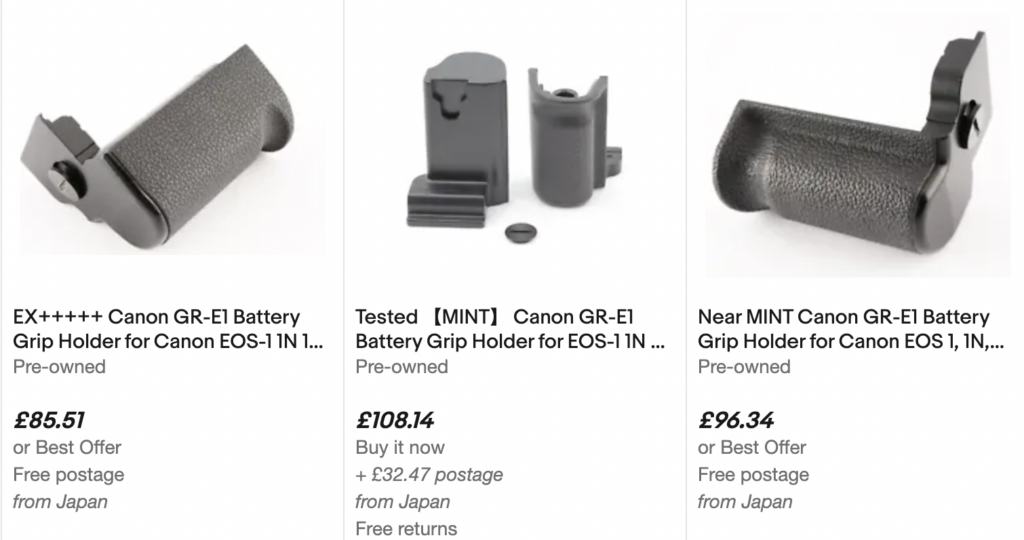

Why does this matter? Well, when Canon sold you an EOS 1n-hs model, they did not include the finger grip that you need to convert it back into a normal sized camera – this was an optional extra! Thanks, Canon. You’ve probably already guessed where this is going, but let’s go there anyway – how much do you think one of these small pieces of plastic sell for today? Place your bets.

If you said “more than the actual camera” then you’d be right. These are the absolute cheapest I can find right now and without one of these GR-E1 grips, you cannot turn your 1n-hs into a lowly 1n. It comes to something when it is cheaper to buy a broken camera and salvage the part you want than to just buy the part you need, but there we go. I was understandably disappointed by this because I’d quite like the option to halve the weight of my camera and make it a bit more user friendly in the process.

There is another problem with this battery grip attached to my camera and that’s the strange case of the missing control dial.

On all other grips I’ve ever used, even the horrible one fitted to the 300D which resembles a paving slab combined with a brick, they all have a control wheel next to the shutter button. I had no idea how much I’d miss this little wheel until I went to spin it round with my finger and couldn’t find it. This makes using the camera in portrait orientation really quite difficult because you cannot quickly change shutter speed or aperture without returning to landscape, setting the camera up and then changing your grip.

According to Wikipedia, there was a grip which did have this control wheel, but honestly I think this is incorrect. Nowhere can I find any picture or reference to a vertical grip for the 1n which has a control dial next to the shutter release. Canon did indeed make a number of battery grips, some of which simply held batteries and offered nothing else, but none of them that I can find have the missing wheel and this baffles me.

Shooting some rolls of film

Normally, I’d stick a 36 exposure roll in a camera, go for a walk and draw some conclusions from the results when I’d run out of frames. One roll through a camera is usually enough to give a fair impression of how it works and the images it produces. If I get odd results or there is obviously a repair needed, I’ll sometimes put a further roll through to see what happens. I tend to find that with film it takes me a surprising length of time to get through 36 shots and when you write about cameras, there’s a need to get to the final images reasonably quickly.

I decided that I wasn’t going to do this with the 1n. The 1n offers so many nuanced features that aren’t in lower end models, multi zone spot metering being one of them, that I didn’t feel I would even come close to really discovering what it could do by just putting one roll of film through it.

For the sake of consistency, I stuck to Ilford HP5+ 400 film throughout the whole process and put three rolls through the camera before developing them all in Rodinal. The resulting negatives gave really uniform results across rolls and I yielded somewhere around 55 frames that were worth keeping and a 9 frame burst on top of that (which I’ll come to later). An approximate 60% success rate when shooting film is not bad at all.

The worlds most expensive GIF?

If I’m going to buy a camera that has the capability to shoot anywhere between 5 and 6 frames a second, I think it would be remiss not to give that a go, even if it is just the once.

With around 10 shots remaining on my first roll of film, I put the 1n into AI-Servo focus, high burst rate and then waited for my daughter to come round the corner on her bike. I held the middle focus point over her as best I could and then held my finger down on the shutter button. It’s like unleashing a really angry mechanical dog.

I made one small mistake half way through the burst – after the first 6 frames I must have let go of the shutter button prematurely as there’s a slight gap between the first part of the burst and the second. Either way, if you ever wondered what it would be like to create an animated GIF out of film, the answer is below.

I’m sure that photographers thought nothing of firing off massive bursts on these cameras in the 1990’s. The price of film then was really quite low and on top of that, people who were paid to do this kind of work would’ve either bulk loaded their film or had massive discounts from suppliers who were selling them rolls by the hundred.

Today, a 36 exposure roll of HP5 is an eye watering £7.15, that’s 19.9p per frame. There are 9 shots in the GIF above, meaning a total cost of around £1.79 to produce a film based GIF. That’s the same as a posh loaf of bread or a 100 bags of crisps from Aldi. It’s not exactly economical to go around spraying 6fps bursts with your 1n, not unless you’re fully loaded or have a fetish for wasting money.

It was fun, though…

Day and Night, Literally

Despite owning an excessive number of film cameras, I had never gone out and done any night photography on film. I have two further confessions to make – I own neither a tripod nor a shutter release cable. These two factors really don’t help when the whole premise of night photography is to remain extremely still whilst using very long shutter speeds. This is where ingenuity comes in (bodging) so I took the lens hood off my 24-105 and used that to prop the camera up on any solid object I could find. As long as I didn’t need anything over 30 seconds, I could use the self timer and that should work.

I’m not sure what I expected from these pictures, but I did have a preconception that night shots on film would be full of grain. This is probably a hangover from using older digital SLR’s where the longer the exposure, the more noise begins to appear in your final image. This is why most DSLR’s have long exposure noise reduction built in where they take two images and use one to subtract the noise from the other.

I was wrong about the noise. Well, mostly wrong at least. In the majority of pictures that came out, they contained no more appreciable noise than any equivalent daylight shot. This really surprised me. On one picture, however, the grain was incredible:

This is not a great picture by any means, and I can think of a few things that went wrong here, but the sky (especially on a full size crop of the image) is nothing but grain and noise. I cannot for the life of me work out why this happened, but one thing it teaches me is that I have so much more left to learn about the characteristics of films and how they react under different circumstances.

I really enjoyed doing something a bit different for once and there’s something quite peaceful about hanging about in the quiet, dark evening waiting for a long exposure to finish. I don’t know whether the image stabilisation on the 24-105 is absurdly brilliant or I’m capable of achieving a zen like state of stillness, but I managed to get two hand held shots to come out completely blur free, when I expected them to be a total mess due to the really long shutter speeds I’d had to use.

The EOS 1n has a light meter which is stupidly accurate. Either that or HP5 is the most forgiving film ever. Every single long exposure I took, every shot in low light (and normal, for that matter) had the exposure absolutely spot on. What I really liked was that in every case where there were mixed lighting conditions, it chose to err on the side of slightly over exposing. It is much, much easier to recover from slightly blown highlights than it is from murky shadows. Light to dark doesn’t introduce huge grain, whereas the opposite is true when you’re trying to rescue an under exposed shot.

Finally, one thing I did remember was to use the little viewfinder shutter to stop light getting back in to the camera during these long exposures and also to turn off image stabilisation – it can get confused during long exposures and actually start to introduce motion into shots. Again, lots to learn about night photography, but absolutely something I’ll be doing again soon.

Conclusions and Learning

Every time I pick up a camera, every roll of film I shoot, every camera I use, I learn something. With the EOS 1n I feel like I’ve learned more in one go than I have for years. Indeed, I go so far as to say that the last time I picked up so much from a camera was when I put my first ever roll of film through my Canon AE-1 Program.

The EOS 1n inspires confidence, not from being a hulking great lump of a machine, but from the subtleties it provides that no other camera does. Once I’d put a roll through where I’d tried various metering modes and lighting conditions, it was clear that the metering was just amazing. It seems to know exactly what you want and when you want it. I stopped bothering with checking what it was doing very quickly and only changed modes when I knew specific spot metering was needed.

I guess this is pretty much the whole point of having a top of the line camera model. It was designed to take on as much responsibility for these nuances as possible, but also to relinquish total control on request at the push of a button. When you ask the EOS 1n to do something, it does it without fuss, without interrupting you or your flow. The only fault I can find with it is the lack of control wheel on the battery grip and in all honesty, if money were no object, I’d convert it into a standard 1n and remove the grip entirely. No one today needs 6fps on a film camera but, to counter balance the argument, it is brilliant to be able to run your camera on readily available AA batteries, even if it does eat 8 at a time.

The 1n has its own quirks and personality which make it stand out. There really is nothing subtle about carrying one of these round. In fact, using this camera was the first time I’ve ever been stopped in the street by people who were interested in what I was using. The shutter noise is something else and is so loud that on numerous occasions I had people turning around with a slightly startled expression on their face. I think this is a combination of people simply not being used to shutter noises any more and that the EOS 1n likes to let you know its there.

To go full circle, I started out with a small confession that I’d not long back said the EOS 50/55 was all the film camera you or I will ever need. So… do I need an EOS 1n or was it simply something that was nice to have? That, my friends, is a tough call.

Does the 1n have one killer feature that beats all other film cameras? I’m not sure it does. The auto focus is great on the 1n, no doubt about it, but actually the EOS 300v performed almost identically. This shouldn’t be surprising when you consider that the 300V is so much newer and has just inherited the inevitable R&D that happened between the 1n being top of the range and the 300V being almost the end of the line for film cameras.

I largely stand by my conclusions about the EOS 50, for £25 it is incredible value whilst still offering great build quality, ergonomics and features. It is only let down by slightly slow AF performance. The choice to buy a 1 series film camera, I think, is fairly easy if you’re not budget constrained – just do it.

The fact is that although it is easy to be put off by price, in terms of value, £100-150 for such a capable piece of machinery just isn’t that expensive. If you buy from a reputable source, you are almost guaranteed to be buying a tool that will probably outlive you or your interest in photography. If you are going to be sensible and only buy one film camera, this should be the one. In “normal” mode, without the battery grip, it is just a beautiful piece of engineering, has every feature and control you will ever need and will smash out roll after roll of almost perfectly exposed film. If I can ever get hold of the missing grip for mine, I’m fairly certain it will become my new go to camera for EOS based film photography.

The problem with the 1n? When you get it wrong, without doubt, the problem is you. Damn.

Share this post: