By the 1870’s photography was already surprisingly advanced, the early Daguerreotype type processes of the 1840’s had been superseded by collodion wet plates around 1850 (film did not come along until 1884) and the race was well and truly on to research and refine faster film processes. One specific goal during the 1870’s to 1890’s was to develop either a camera, film or both which was sensitive enough to capture and freeze high speed motion. Shutter speeds of 1/2000 and above that we casually use on our cameras today were a pipe dream. Sure, you could probably create a mechanism which would open and close a shutter for such a short period of time, but there certainly wasn’t a way of capturing such a fleeting moment of light.

The 1800’s was nothing short of a period of enlightenment in the field of science and scientific discoveries. Absolute titans of chemistry and physics were quite literally making world changing discoveries and inventions from their homes. It’s unimaginable now, but this was a time where people feared electricity and they genuinely didn’t know the answer to a question that proved surprisingly difficult to prove one way or another.

The question was this: does a horse ever have all four feet off the ground at the same time? The story of this question and how it was finally answered is fascinating.

In this post:

Engineering Gods

It would not be excessive to suggest that Great Britain saw the greatest pace of change in its history during the Victorian era. So much was discovered, so much changed that suddenly these trouble makers called scientists started to prove things that made the public begin to question the very existence of God, something which prior to the era would’ve been unthinkable. Indeed, this has since been coined the Victorian Crisis of Faith in recognition of the adjustment that society had to make to fit in with their new found knowledge.

Education and engineering were the key facets that drove change for the Victorians. Children had the opportunity to go to school as it had been made both free and compulsory for the first time. In the mid 1800’s, Britain was the world leader in many of the newest technological advances. Absolute historical giants such as Brunel were coming up with ingenious engineering projects, tunnelling under the Thames, making the greatest and fastest steam ships the world had ever seen and standardising time itself to name but a few of his achievements.

At the same time, Britain led the way in the development of railways and locomotives around the world. This wild new method of travel made the entire world seem so much smaller and more accessible. Brunel, with his unnatural tenacity and foresight, created a network that meant you could buy a ticket in London for a journey all the way to the Americas – all on his trains and ships. When Stephenson unveiled his Rocket at the Rainhill Trials in 1829, reaching the mind bending speed of 29mph, people were utterly and genuinely terrified.

It makes sense when you think about it. This was a time when the speed of travel was limited to how fast you could get a horse, or several horses, to run. That was it. To suddenly find yourself confronted by the sight of a large steaming machine, rattling and clunking along at previously unknown speeds must have seemed unnatural to say the least.

Victorians, though, accepted and adapted to change at a rapid pace and these railways along with other reforms such as limits placed on working hours (yes, they invented weekends too) meant that whole new industries were created, a new era had been born – leisure and tourism. Now the newly emerging middle class were travelling to places on their days off, family trips to the seaside were experienced for the first time, the concept of “amusements” created an economy that couldn’t have been imagined a few decades earlier.

It would be quite wrong to suggest that this was an era of sunshine and leisure, huge problems persisted with low quality housing, poor healthcare and God help you if you ever needed to see a “surgeon.” You were better off taking your chances and seeing if your leg would just do you a favour and drop off of its own accord. However, the sheer number of amateur scientists and inventors up and down the country created a golden era of experimentation, discovery and ground breaking developments. The Victorians had an almost insatiable curiosity that had simply not been seen before – they were not content with “the way it is” and were constantly asking “why?” This attitude meant they didn’t give up – when people told Brunel it was impossible to build a suspension bridge of such length in Clifton, he did it anyway and proved everyone wrong.

These Goldilocks conditions of the time fed in to the photography we know and take for granted today. Curiosity about the world around us led inventors to seek ways to slow down or stop time, to be able to closely and scientifically analyse the way in which people, animals and objects moved or changed over time. There was a real need for some kind of machine which could provide the answer to so many questions that were otherwise impossible to answer. Those canny entrepreneurs in the newly fledging leisure industry saw the lure of photographic keepsakes of these new holidays and adventures to new places that people were now taking. The only problem was, if you wanted to take a “quick” photo, you’d better set aside 15 minutes or so to sit rigidly still. The scene was set, the outcome was obvious, those pioneers were going to find a better way to record images.

Masters of motion

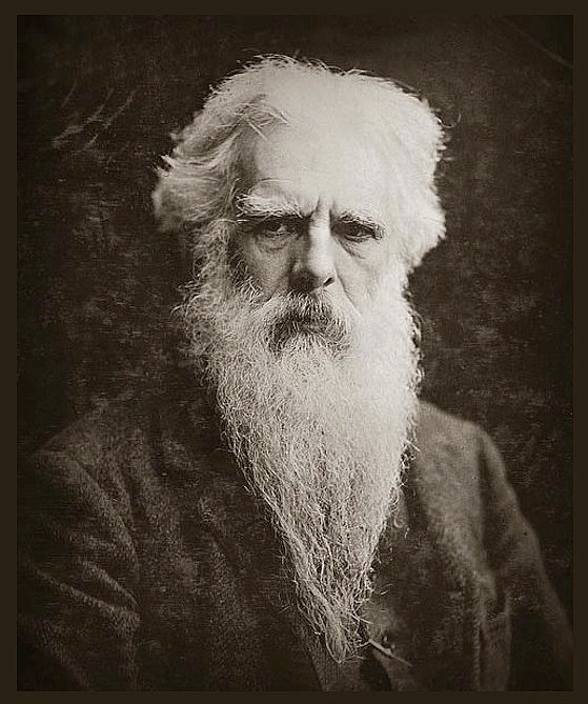

The theme running throughout the Victorian era was one of curiosity, it was a time of enlightenment through questioning, observation and experimentation all made possible through advances mostly made by people who just didn’t understand the concept of giving up. Two men who personified this attitude were Eadweard Muybridge and Ottomar Anschütz, both separately pursued and advanced the field of high speed photography.

Muybridge

Born Edward Muggeridge in 1830, Muybridge lived a fascinating life in both England and the United States. Clearly not someone who liked his birth name, he gradually evolved his own name over his lifetime, finally settling on the Old English, Nordic influenced Eadweard. His name apparently caused others a great deal of confusion throughout his life to the point where his gravestone carries a mis-spelling of his last name as “Maybridge.”

Muybridge began life as a bookseller and showed no recorded interest in photography until a stagecoach accident during 1860 in Texas and a subsequent severe head injury apparently “significantly changed his personality.” Muybridge returned to the UK to recover from his injuries and it was during this time he learned wet plate photography before returning to the US to create and exhibit landscape works.

He was definitely not a man to get on the wrong side of. Muybridge’s wife was 20 years his junior and they seemed to be quite different personalities – he was an introvert and she a woman who desired a social life. Initially, he showed no concerns about her frequent trips, social events and so forth and was apparently aware that she was having an affair with Major Harry Larkyns sometime in the early 1870’s. Having discovered evidence in 1874 about the seriousness of their relationship, the fact that there could possibly be a question of the paternity of their then newly born son and that they were still writing letters and seeing each other in person, he decided to set the record straight. He arrived at Larkyns’ residence, announced that “I have a message from my wife” and promptly shot him dead.

Miraculously, Muybridge was acquitted of murder. Miraculous is the exact phrase to use because during his trial, Muybridge actually contradicted his own defence team who had argued his stagecoach injury had rendered him insane. Whether through insanity or not, Muybridge decided to tell the court that, in actual fact, he was not insane, had fully intended to murder Larkyns and had no regrets in doing so.

You’d think at this point that he’d have signed his own death warrant, but no, the jury decided to come to his rescue by delivering a verdict of “justifiable homicide” on grounds of “the law of human nature.” Translated, this means they thought it was more than justified to murder someone who you’d recently discovered was shagging your wife.

Honestly, I think he was unhinged. His behaviour became obsessive after his accident and this almost certainly manifested in his interest for the motion of humans and animals. He began in the 1880’s to develop very clever methods of setting up multiple cameras (sometimes well over 20 at once) which were all triggered by various threads that were tripped by the human or animal he wanted to capture. His most famous set of photographs are that of the horse shown below:

Muybridge had done it, he had proven that when a horse runs, there is a period of time when all four legs were off the ground. Not content with this, he developed a form of electrical flick book projector called a “zoopraxiscope” which would animate his photographs for audiences to see. There’s no denying, he had an excellent scientific mind.

But he was also… disturbing.

The remainder of his work on human motion is bizarre. It starts out understandable enough, I guess, with him photographing the motion of a tennis player serving a ball. Nothing odd there, surely? Well no, only he insisted the tennis player was entirely naked.

I actually stopped researching him at this point, because… well, it just became deeply uneasy. His other works include a woman walking across stepping stones – naked, a woman serving a cup of tea to another woman – naked from two separate angles and finally two boys playing leapfrog – naked. These days, Muybridge wouldn’t have to worry about a conviction for murder, more one for being wholly inappropriate to a sickening degree.

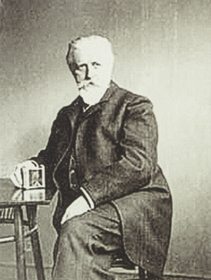

Anschütz

Coming to the rescue of decent individuals in history, then, is Ottomar Anschütz. Here is a man who at almost the exact same time as Muybridge was separately working on freezing the motion of moving objects. Anschütz, however, contributed far more to the development of film and camera technology than Muybridge had. Where Muybridge had found creative ways to use existing technology to freeze and capture motion using multiple cameras and trip wires, Anschütz developed new cameras and shutter designs that offered unprecedented speeds, most famously being able to capture the flight of a cannon ball being fired.

Ottomar knew that the key to freezing an image was to have the highest possible shutter speed. The only problem was that, at the time, shutter designs ranged from “take the cap off by, count to three and stick it back on again” to the slightly more complex but still slow rotary type shutters that stuck around on cameras well into the 1950’s and even 1960’s in the case of some cameras.

This is where translation has completely failed me, because in my research I could find that he invented the cloth focal plane shutter / curtain design that even appeared in Canon A Series cameras, but I couldn’t really understand the details. The invention, however, was a complete revelation as now for the first time not only could motion be frozen in ways that had never before been possible, but photographs could be taken with a camera that was hand held. This was a complete revolution.

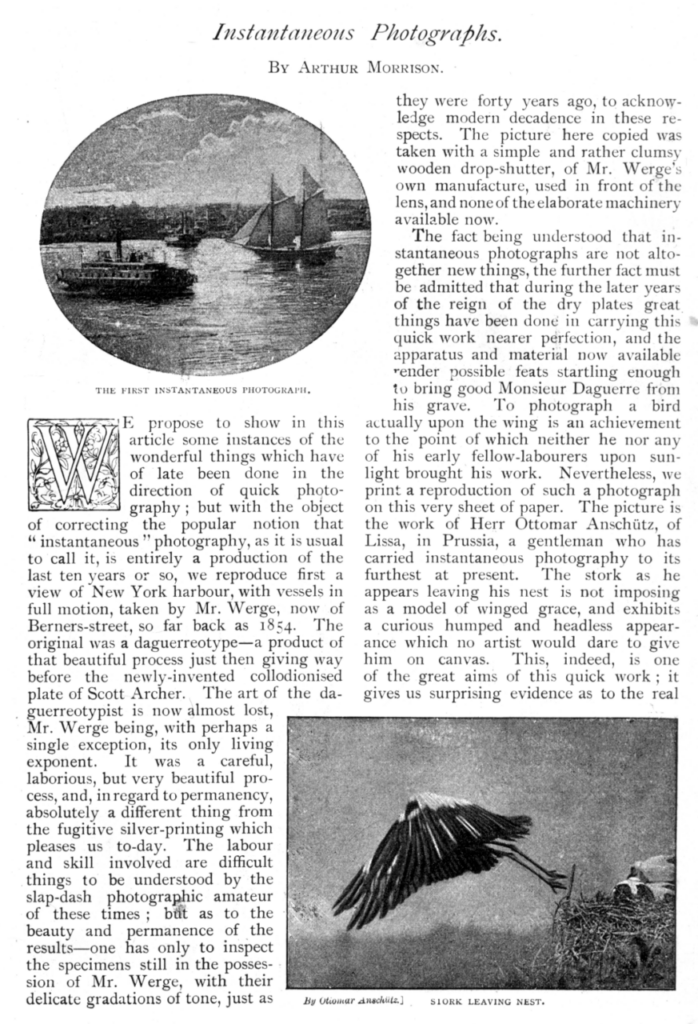

The June 1882 issue of Strand Magazine (the magazine in which the original Sherlock Holmes stories were first published) wrote a wonderful article all about the wonders of “the instantaneous photograph” that is full of praise for Anschütz and his work. The author, and I daresay most Victorians of the time, was absolutely fascinated by the discoveries and curiosities that had been revealed by freezing various things, usually animals, in motion.

Anschütz achieved great notoriety for his series of still images, especially those of Storks, and had his work displayed at various prominent exhibitions. Not a man to stand still, he quickly turned his attention to motion pictures for the rest of his career, realising that still images were one thing but animating and projecting them would be something else entirely.

It is bizarre to think that Muybridge and Anschütz worked almost simultaneously on exactly the same idea – that of understanding the true motion of moving objects. It is fascinating in retrospect to see the entirely different solutions to the problem that either inventor created and even more impressive that they both found ways to reanimate their subjects using primitive projection technologies also of their own invention. For everything we take for granted in both still and motion picture technology today, there was a starting point in history before which the very idea of what we know today would’ve been completely unthinkable. To have been there at the time must’ve been utterly mesmerising.

A modern approach to motion

Having stumbled across the story of fast shutter speeds and freezing motion in a camera, I thought it’d be fun to give it a go using modern technology. I could’ve tried to be a little more authentic and used the film hungry Canon EOS 1N-hs but this will eat a film in 3 seconds (literally) and frankly, I can’t afford experiments like that any more since the price of film has gone largely through the roof.

Not to worry, I thought, this is the perfect excuse to get the 1D Mark IIn out and use the absurd burst mode with its 45 point AF and AI focus it was quite literally designed for the task. As I was soon to find out, whilst the camera may be designed for the task, I wasn’t.

The first issue was finding a subject. The Victorians had turned to horses, dogs and as we’ve seen, naked sports people. I have access to none of those things so I thought I’d make do with the cat. This is where things got really silly, I gave my daughter a piece of string and orders to “make the cat go mad” in the garden. I then duly fired off about 100 shots and all of them, and I mean all, were utterly woeful!

Yeah. Not exactly ground breaking, is it?

This picture is the result of a combination of factors coming together to make a perfectly terrible image. The first problem is the most obvious – the cat is fast and my shutter speed too low. At 1/500, ISO 640 I had been far too conservative, something around 1/1000 perhaps may have solved some of the blur issue, but not all.

The second problem is the lens. I used a 24-105 F4 L and, whilst an incredible and versatile lens, it has image stabilisation built in. This isn’t modern, multi axis image stabilisation either and so when you’re panning around trying to take images of a fast moving subject, you’re actually better turning it off to avoid blur being added to your photos. It was time to learn from mistakes and have another go!

Turning IS off and whacking the ISO up to 1600 made a big difference, now shutter speeds of over 1/1000 were available. I also changed the AF tracking to centre point only which helped avoid a lot of shots where the grass was perfectly in focus but not the subject.

Although now shooting at a much higher shutter speed, I was surprised that even 1/1000 or 1/1250th of a second wasn’t always fast enough to completely freeze the motion of the cat darting about the place. I think a third effort would have to involve a faster lens and speeds up to 1/2000, that’d probably give an even higher quality of final image than the ones I settled on here.

Inevitably, for a quick play in the garden, the shots are nowhere near perfect but there are some fun pictures in here of the cat going slightly mad for a piece of string. I’d like to have captured something a bit more spectacular but I’d got to the point where the cat gave up being a willing subject and my daughter found something far more interesting to do. A third try will have to wait for another day.

Conclusions and Learning

It’s actually quite eye opening how difficult motion based photography is if you’re not used to it. In the past I’ve had a go at panning with subjects, shooting motorcycle racing and a few other things and they came out “ok” but, of all things, I met my match with the cat and a piece of string.

When you consider I used an ex-professional model of DSLR, the sole design focus of which was to capture moving subjects, I am even more impressed that these Victorian pioneers of photography managed to capture anything like the crisp, clear images they did. It was through their desire for understanding, to answer questions the answers to which had previously been out of reach, that drove on developments in camera technology that lead us directly to where we are today.

Motion capture is great fun and an even better excuse to crack out a camera you don’t normally use and to let it loose in the way it was designed to be used, but take it from me, it’s not as easy as it looks. You should definitely give it a try, but for me – I think I’ll go back to my film camera and the streets now!

Share this post: